Digital Architecture?

‘Work in Progress’

UTS Architecture Exhibition

Thursday 15th December 2005

As a regular visitor to the UTS Architecture Exhibition, I noticed that this year something was different. On closer examination, a bifurcation in the work was evident. On one side of the divide were student projects consisting of buildings with structure, walls, windows, doors and roofs…generally where one expects them. The other half of the work required some extra effort. At a quick glance, these projects looked more like isolated frames from the latest CGI Hollywood science fiction film than architectural proposals for sites in and around Sydney. A few questions revealed an institutional basis for this divide: the ‘Work in Progress’ exhibition represents the first wave of graduates who have undertaken units within the ‘Digital Architecture’ stream being offered at the UTS Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building. It is no coincidence that the recent evolution of architectural education towards the digital is also reflected in a paradigm shift occurring in contemporary architectural research and practice. Rem Koolhaas, Dutch architect and theorist, has neatly coined this situation the ‘Box vs. Blob’ battle. (Koolhaas 2004: 70)

If we agree that your current house or office is likely to fall under the category of ‘Box Architecture’, then ‘Blob Architecture’ (a term fashioned in the mid-nineties New York scene) probably resembles something closer to the oscillations of your computer screen-saver. This ‘battle’ can also be situated within ongoing ‘Analogue vs. Digital’ debates proliferating across all mediums today. For the sake of clarity, I will take ‘Blob Architecture’ and ‘Digital Architecture’ as one and the same, for now.

So what does Digital Architecture actually really mean for our houses, workplaces, public spaces and cities? In response to this question, I will begin with a brief historical context and then jump into a ‘case-study’ from the exhibition to relocate the key issues within a Sydney context.

In a McLuhanite sense, the medium, or representation, through which architectural design is communicated is never neutral. Designing - as a process of thinking, sketching and documenting spatial possibilities, is not independent from the medium within which it occurs. For example, one might briefly consider the bold strokes of Mies van der Rohe’s charcoal stick, the primary-colour sketches of Le Corbusier and the renderings of Frank Lloyd Wright, with respect to their built work: The Seagram Building, Unité d’Habitation and Falling Water respectively. In doing so, it is evident that the preferred design ‘tools’ of each architect bear strong relationship with the architectonic qualities of their buildings and spaces. If we apply this logic today, where the tools for manipulating space now exist as software commands operating within a virtual domain, then it would seem reasonable to expect vastly different types of buildings and environments, from up- and-coming architects.

Over the last decade, architects - like many creative professionals - have taken advantage of increasing computing processing power allied with cost-effective, advanced software programs. Whilst 2D-CAD (Computer Aided Design) has existed for some time in the form of a ‘drawing board replacement’, the emergence of Digital Architecture is largely due an appropriation of 3D modeling and animation software developed for the gaming and entertainment industries. However, where most gaming environments seem to be satisfied with simulacra of ‘real’ world building stock, Digital Architects have taken up the challenge of defining a new spatial aesthetics pertinent to the Information Age.

But here things get a little trickier. Architects working with software programs, which excel at the simulation of virtual environments, soon encounter problems when they also profess a desire to also contribute to the built environment. This is problematic for two reasons: firstly since architects are used to ‘assembling’ buildings from a catalogue of prefabricated components (think window frames, garage doors, I-beams etc) and secondly, a key dimension in any animation software is ‘time’. In other words, the Digital Architect must negotiate an awkward transition from the fluid forms of non-Cartesian geometry spiraling on their lcd screens (in 3d Studio Max or Maya software) toward their eventual stasis: as habitable form and shelter.

The first part of the problem has largely been solved: access to laser and rapid-prototyping technologies (eg Stereolithography) is becoming increasingly available. This process is when a machine directs a computer controlled laser to ‘print’ or ‘form’ a 3D physical-model from information contained within the file of the 3D virtual-model. And it is here that the real and the virtual share an exciting zone of intensity. This process has ramifications at all scales of production, from a scaled prototype of an entire scheme to an interlocking building component to be used in the construction process. Thus, the term ‘Digital Architecture’ is already being rivaled by the term ‘Non-Standard Architecture’ (Benjamin 2004: 034). The second part of the problem, how to negotiate the temporal, presents more difficulty. If we consider any given animation program, such as the ubiquitous Macromedia Flash, then at some point forms animated over time need to ‘STOP’ [Flash ActionScript Command]. In the context of Digital Architecture then, at which point in the design process should the architect decide to ‘stop’ a design, so it is ready for construction? Also, in the transition from four dimensions to three - how can time and movement be transfigured into the built project?

To answer these questions, let us turn to a case study from the exhibition. I have selected a scheme by graduate architect, Jarrod Lamshed, which impressed as a convincing representation of the kind of transformations we might expect in our built environment.

‘Architectural Diagrams: Temporal Shifts in the Urban Context’

Project by Jarrod Lamshed, UTS Design, Architecture and Building.

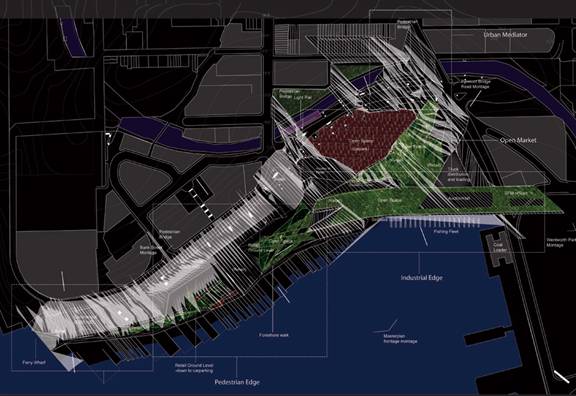

“The project manifests itself in the form of a new ‘fish market’ and ‘urban park’ on the edge of the city.” (Lamshed 2005)

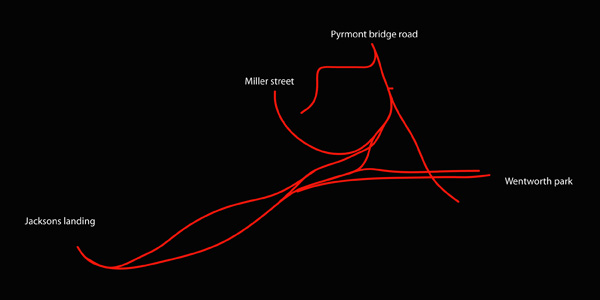

1. Diagram: Movement (& Circulation)

The traditional design process could be described as a ‘black-box’: the journey toward a ‘solution’ via consideration of a complex set of information based ‘problems’. In this process, the role of intuition is often emphasised to cover the vagaries of a frequently nebulous negotiation of client requirements (or program), planning and building controls, historical precedent and urban context. However, in our case study of Digital Architecture, Lamshed presents a tightly bound hypothesis: “What is the role of the Architectural ‘Diagram’ within the urban context?” (Lamshed 2005) Here, it seems that from many possible beginnings, a key aspect of the architectural experience has been isolated and intensified in order to ‘generate’ an architectural response. Given our dilemma of the temporal in Digital Architecture, the focus here has been to identify existing and latent patterns of movement (or circulation) operating within the Sydney Fish Market site and edges. This design process, which treats the architectural site as a dynamic ‘system’, asserts itself in opposition to the heroism of the Modernist architects, who sought to superimpose their grand visions upon a Tabula rasa. Lamshed justifies his approach as “an attempt to reassess and reconfigure the relationship between program and circulation in the making of architecture on an urban scale.” (Lamshed 2005)

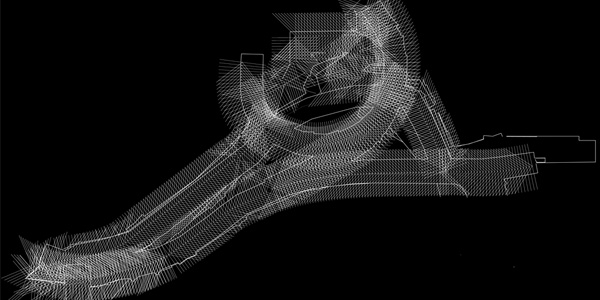

2. Diagram: ‘Array’

While the red computer rendered ‘sketch’ in Step 1 might still be equated to an architect’s ink sketch on the back of the restaurant napkin after the client dinner, what happens next is markedly different…

The next stage of the Digital Architecture process involves a two dimensional ‘array’ of ‘structure’ along the movement Diagram. The Diagram now incorporates parametric information which can be manipulated toward the determination of three dimensional form. Here, one needs to negotiate the new architectonic language (derived from mathematics) of ‘splines, nurbs, fields and folds’ which presents a challenge to its Cartesian equivalents of ‘points, lines, planes and volumes’. Also of significance, is that the role of the Digital Architect, is not superseded by computer software, but rather redefined as a processor/manipulator of information. For example, the array operation involves the selection of an (abstract) 5m x 40m structural grid extruded along the movement Diagram. This seems enacted from both an intuitive and pragmatic understanding of the extent of territory and floor space required by the program, within the given limitations of the site and existing urban infrastructure. Lamshed’s experimental design strategy, based upon the Architectural Diagram, is informed by Professor Andrew Benjamin. (Benjamin 2000)

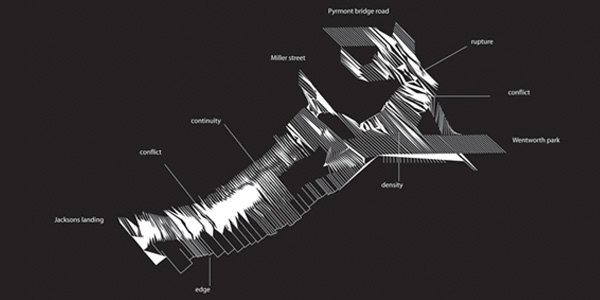

3. Diagram: ‘Mapping & Transformation’

Next, the Diagram enters a realm of further digital manipulation through software operations described in terms of “density, rupture, continuity and conflict.” (Lamshed 2005) Here, the task is to project multiple extents and edges from the Diagram to define a series of boundaries. The various elements of the program (or brief) include: a retail arcade, a night soccer venue, an auction house and park/landscape areas with sheltered pedestrian access. At this stage, distinct spatial requirements are correlated with the evolving Diagram via processes of mapping and transformation.

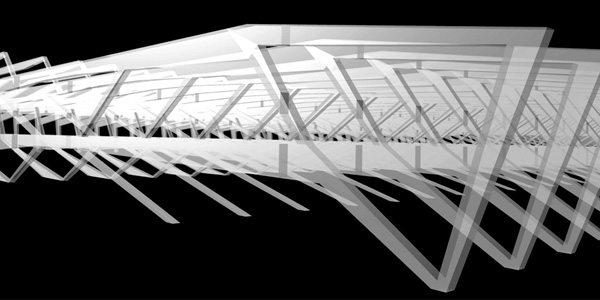

4. Diagram: ‘Deformation’

It is only now that we can witness an ‘emerging’ form of the architecture. This is informed by a series of (parametric) ‘index’ points which retain the temporal complexities of the initial Diagram. The goal here is to design a structure/enclosure which maintains the temporal, plastic and dynamic qualities embedded in the initial ‘movement’ Diagram - whilst obeying the various structural, environmental, planning and amenity requirements expected for any building. And it is here we could say that the diagram ‘stops’ – toward becoming shelter and enclosure.

It needs to be mentioned that the four stages highlighted above are a simplification of Lamshed’s spatially dexterous moves, for the sake of clarity to a wider audience.

Proposed Fish Market & Urban Park

Images by Jarrod Lamshed

A key feature of Digital Architecture is its inability to be represented by the language of traditional architectural drawings: plans, sections and elevations. In their place, 3D photomontage/visualisations and real-time ‘walkthroughs’ allow a viewer better access. I have included an overall site plan (above) in order to place the following sequence of images in context, but firmly believe that the rendered images best emulate the fluidity of the scheme.

Photomontage of Sydney Fish Markets in harbour context, Anzac Bridge beyond.

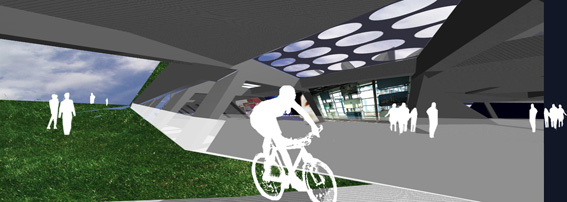

The building and the terrain seamlessly integrate to form the Urban Park.

The bridge under the existing freeway allows increased pedestrian access to the Sydney Fish Markets.

The Urban Park stimulates a diversity of activity in, around, above and below the enclosure.

The ‘Auction House’ within the Fish Markets showing fenestration and amenity.

A ramp between commercial and leisure spaces with skylight over.

These photomontages give a strong impression of the potential for Digital Architecture. A few things come to mind. For one, the various ramps and pedestrian devices seem to dismiss altogether the conventional notion that the floor of a building needs to be flat and instead contribute to the spatial fluidity of the enclosure. In fact, this ‘building’ seems more analogous to a terrain, landscape architecture or land art. It is not surprising that similar metaphors, based upon geological strata (of forests, canyons, dunes and glaciers) have been recently adopted. (Schumacher 2004: 28) Also, the ‘building’ appears to function as a homogenous entity: the fenestration is defined within the interstitial spaces of structure, the roof folds downward to form the walls, which intersect with the ground plane. Overall there exists an equivalence of architectonic elements in both their form and materiality. In summary, this building performs as an interactive ‘system’ or ‘network’: which distributes a complex series of spaces and events, including bridges, motorways, parks, markets, industrial, sporting, commercial and retail spaces. In addition, the images presented reveal the building as a ‘container’ for the (ever-increasing) production/ and consumption of interactive digital media content incorporated into various surfaces.

All this complexity ‘generated’ from the Architectural Diagram. What is clear, from Lamshed’s project, is that along with the seamless connectivity currently being enabled between digital technologies and the material world (evident in our latest digital gadgets and appliances), notions of networks, software, connectivity and interfaces will become increasingly relevant descriptions of our buildings and cities in the (near) future.

ReferencesBenjamin, A. (2004) “The Standards of the Non Standard” in Architectural Review Australia 087: p34.

Benjamin, A. (2000) “Lines of Work: On diagrams and drawing” in Architectural Philosophy: Repetition, Function, Alterity pp 143-55

Koolhaas, R. (2004) “Box vs. Blob” in Content pp70-71

Lamshed, J. (2005) Architectural Diagrams: Temporal Shifts in the Urban Context, UTS Dissertation

Schumacher, P. (2004) Digital Hadid: Landscapes in Motion, Basel: Birkhäuser

Links

www.emergentforms.blogspot.com

www.noxarch.com

www.zaha-hadid.com

Alex Munt is an Associate Lecturer in media in the Media Department, at Macquarie University. His research focus is on Digital Cinema. He also teaches architecture and design at the University of New South Wales.