Fantastic Giants: Charlton Comics' Monster Movie Adaptations

Christopher Hayton

Preface

Charlton Comics as a company came into being in 1946, and remained in operation until 1986 (Cook & Irving 2000). During its existence Charlton explored, leaving no stone unturned perhaps more than any other comic book company, almost the full range of genres for which the industry was known during its day. Charlton's ground-breaking monster movie comics of the early 1960s represent a poorly recognized but significant contribution to the evolution of modern comics. The history of comic books views the early 1960s largely in terms of the superhero revival, which certainly eclipsed Charlton’s monster movie adaptations, then and in the minds of historians today. But while superhero comics continue to be a mainstay of the mainstream comic book industry, an important corner of the modern market owes its origins to Charlton’s experiment with creature features.

In terms of artistic contribution, Charlton’s monster movie comics also warrant recognition. A number of comic book industry greats worked at Charlton early in their careers, and the monster movie books showcase pencil work and inking by artists recognized today for their distinctive styles. Moreover, the extensive body of work of the books’ writer, Joe Gill, offers a rich field for analysis, as this article’s look at his monster movie adaptations will illustrate. The present article, then, seeks to draw the readers’ attention to Gill’s work as a source of natural social commentary, and also to the illustrative work of Charlton artists, particularly Steve Ditko, to be found in the monster movie books, in addition to the innovation that the books themselves accomplish in terms of genre founding.

Introduction

Comic books and motion pictures have exchanged content more-or-less since their inceptions as art forms. Whilst modern movies based on comic books are the more familiar arrangement, because of the recent and commercially successful adaptations of, for example, Spider-man, The X-Men, Daredevil, The Incredible Hulk, Batman, Superman, and Catwoman, there exists a variety of comic book series that are, in contrast, based on motion pictures. Current examples include the range of Star Wars, Alien, and Predator comic books published by Dark Horse Comics over the last two decades (Dark Horse Comics 2009) and which form a major component of this successful modern company’s output.

Comic books have often taken on the role of translating various genres of popular culture into a form that can be held in the hand, stuck in the back pocket, and indulged in at leisure in a variety of situations where the movie, television, radio, or even book or rock concert versions were not available. Once the showing of a particular movie, screening of a television show, or broadcast of a radio show had passed, the public, in the days before DVDs, video cassettes, and even tape recorders, had very limited or no subsequent access to these events, unless television companies decided to show the old movie or re-run old shows.

In the realm of comic book adaptations of movies, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories of 1940 represents an early marriage of cartoons and comics which persists to the present day. Innovative comic book adaptations of specific movies with human actors are exemplified by National’s Movie Comics (1939), Fiction House’s Movie Comics (1946-47), and Fawcett’s Motion Picture Comics (1950-53). Using graphic storytelling to re-present actual movies, Movie Comics #4 (1947), for example, re-tells the story from Slave Girl, a film that starred Yvonne De Carlo, and Merton of the Movies that featured Red Skelton (Figure 1). Dell’s Four Color series (1939-62) contained many cartoon, movie, and television adaptations. Dell’s Movie Classics (1963-69) and Gold Key/Whitman’s Movie Comics (1962-84) continued the non-cartoon movie adaptations genre in the same format of comic book versions of individual movies.

Figure 1. Movie Comics #4 (Fiction House, 1947). Copyright respective copyright holder. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Authoring an entire series using a particular movie or group of related movies as the seminal idea is demonstrated by an assortment of western comic books from the late 1940s through the 1950s. These books featured actors or characters from B-rate western movies whose origins stretch back into the 1930s. Tex Ritter, Hopalong Cassidy, Lash LaRue, Jimmy Wakely, and a whole posse of others adorned the newsstands during this age when the American public was fascinated by the rugged image of the Wild West. The 1950s also saw a diversification of comic book themes based on the screen lives of movie stars such as National’s The Adventures of Bob Hope (1950-68), and The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis (later just The Adventures of Jerry Lewis) (1952-71), characters from radio shows such as Atlas’s My Friend Irma (1950-55) written by Stan Lee, and television shows, for example, Dell’s I Love Lucy (1954-62) and National’s The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1960-64).

Comic book publishers, like other businesses involved in the production and dissemination of popular art, are looking to make money, which does not imply that the material they produce bears no artistic merit. Instead, a popular artist whose work resonates with a large number of people, because it makes some connection on a meaningful or even superficial level, can be considered accomplished.

The Comic Book Industry in the Late 1950s and Early 1960s

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw a rise to revived prominence of the superhero genre in comic books, with the well-documented dawning of the so-called Silver Age of Comics. National cautiously developed a new line of science-fiction based superhero characters, beginning with The Flash in Showcase #4 in 1956 (Daniels 1995). During this transition the comic book industry flourished and other genres, for example, western, romance, war, science fiction, and monster/mystery books, that had been the mainstay of the industry during the years following the introduction of the Comics Code Authority, still had their place in the market. Stan Lee and Atlas/Marvel Comics continued to rely heavily on their monster/sci-fi/fantasy titles in 1960 (Strange Tales, Journey into Mystery, Tales of Suspense, and Tales to Astonish), although National by this time had already added The Challengers of the Unknown, Space Ranger, Adam Strange, Rip Hunter Time Master, Green Lantern, the Legion of Super Heroes, Supergirl, and the Justice League of America to their ever-growing science fiction and superhero portfolio. Other comic book publishers made attempts to create science fiction superhero competition for National, notably Archie’s The Fly (1959) drawn by Jack Kirby, and Joe Gill’s Captain Atom in Charlton’s Space Adventures (1960), drawn by Steve Ditko.

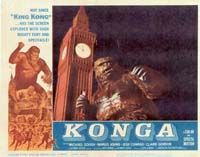

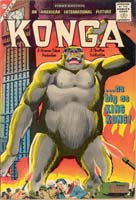

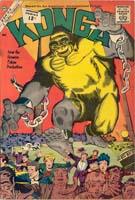

Into this melting pot of attempts to carve out the biggest piece of the comic book industry pie at the beginning of the 1960s, Charlton Comics added Konga #1, drawn by renowned comic book artist Steve Ditko. John Romita Sr., the artist who later succeeded Ditko as pencil artist on the Amazing Spider-man in 1966, commented that “when you talk about artists like Steve Ditko, you have to put them in a special category... when you’re in their world, you don’t have to look around and see which part of it reminds you of them; buildings, figures, storytelling, everything about them is distinctive” (Bell 2005). Konga #1 was no exception, being replete with trademark Ditko imagery. The Konga #1 comic promoted the American International movie Konga, a monster/sci-fi movie clone of King Kong, starring Michael Gough, familiar in more recent years as Alfred, Bruce Wayne’s butler, in the Batman movies of the 1990s.

At that time Ditko was already well-established and working simultaneously for both Charlton and Marvel, and he was soon to enter his most productive and commercially important period with the development of Spider-man and Doctor Strange. Ditko’s Konga #1 was adapted from the movie script, rather than from the screen version, by writer Joe Gill. In 1961 Gill and Ditko then adapted a Godzilla clone monster movie, Gorgo, released by Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer. Following the first issues of these two titles, Gill extrapolated on the original movie plots to create two comic book series, Konga and Gorgo eventually printing on alternate months. Charlton added a further Godzilla movie clone adaptation, from Sidney Pink’s American International picture Reptilicus, at the same time that they began the serial extrapolations of Konga and Gorgo, later re-naming it Reptisaurus and thereby making a trio of sci-fi creature feature adaptation comic book series.

Comic book publishers made public statements of their distribution figures, and in the early 1960s Charlton monster books these appeared on text story pages approximately annually. The numbers reported are quite impressive. For Konga, the figures quoted were 187,778 (March 1963, average copies per issue in previous year), 112,700 (March 1964, average circulation per issue in previous year), and 234,331 (April 1965, average print run in previous year). For Gorgo it was 143,818 (February 1963, issues sold to paid subscribers in previous year), 231,676 (February 1964, average print run in previous year), and 184,778 (September 1965, average per copy distribution in the previous year). While interpretation of these figures is not necessarily straightforward, some comparisons can be made with other publishers from the same time period. Average paid distribution for issues of Superman (DC) in 1962 was 740,000, and for issues of Amazing Spider-man (Marvel) in 1966 was 340,215 (Miller 2009). However, a more realistic comparison would be with titles from similar genres: Mystery in Space (DC, 1962) averaged 190,000 copies, Unknown Worlds (ACG, 1963) 143,468, Turok, Son of Stone (Gold Key, 1963) 276,550, and Strange Tales (Atlas/Marvel, 1963) 189,305 copies per issue (Miller 2009). While distribution of the Charlton monster movie books did not reach the levels of the popular superhero books, their print runs compare well with comics of similar genre from the time period.

The three Charlton movie monster adaptations appear to have been the first substantial examples of comic book series grounded in a sci-fi movie plot but then taken off in their own directions, in this case by prolific comic book writer Joe Gill, who admitted to having enjoyed working on Gorgo and the other movie comics (Irving 2000). Artists working on these series included the celebrated Steve Ditko, and the talented but severely under-rated duo of Bill Montes and Ernie Bache, as well Dick Giordano and other regular Charlton artists of the time. These titles set a successful precedent for later attempts by Marvel and other companies, who also created series based on sci-fi movies such as Logan’s Run, Planet of the Apes, Star Wars, Godzilla, 2001 A Space Odyssey, Alien, Predator, etc. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, comics of this type form a large part of the material produced in recent years by Dark Horse Comics. In finding ideas for Konga, Gorgo, and Reptilicus story lines, Gill drew on the full range of themes popular in comic books at the time - romance, espionage, monster vs. monster, alien invasions, subterranean dwellers, anti-communist propaganda - to name a few, the popularity of each theme owing at least something to its significance in the consciousness of society as a whole during that time period.

The comic book series based on the ideas from a science fiction movie is currently a prominent fixture, and is even turning full circle and spawning new movies based on the adapted stories from the original movies. A case in point is Alien vs. Predator, a movie version of Dark Horse’s decision to explore, in comic book form, what might happen if the aliens encountered the predators.

Steve Ditko and Joe Gill in the Early 1960s

Steve Ditko largely worked for Charlton Comics during the 1950s, with the years from 1956 through 1958 seeing him develop his dual allegiance to both Charlton and Atlas (Marvel). Atlas had abandoned superhero comics and their late 50s line consisted mainly of fantasy, romance, war, and western comics. 1957 was simultaneously a difficult year for the Atlas company and a very productive year for Ditko at Charlton, but by the beginning of the 60s Ditko’s role at Atlas began to take up more of his creative output. Ditko was drawing the same kind of fantasy/mystery/sci-fi stories for both companies but in 1961 things changed. In 1960 Ditko had drawn the first issue of Konga, but following Gorgo #1 in 1961, his work on Charlton mystery books more-or-less ceased, temporarily, and his Charlton work became focused on the monster movie titles. At Atlas his regular monthly contributions to the four main fantasy titles, Strange Tales, Journey into Mystery, Tales of Suspense, and Tales to Astonish continued, but he also became involved in a new project, Amazing Adventures. With issue 7 this title became Amazing Adult Fantasy and all Ditko, purely a vehicle for his talent in illustrating this type of story, and the eventual spawning ground for the Amazing Spider-man, Ditko’s co-creation with Stan Lee (Lee & Mair 2002).

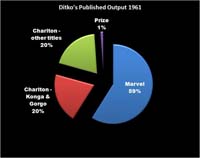

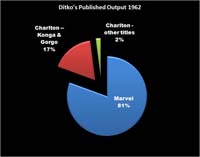

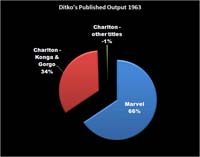

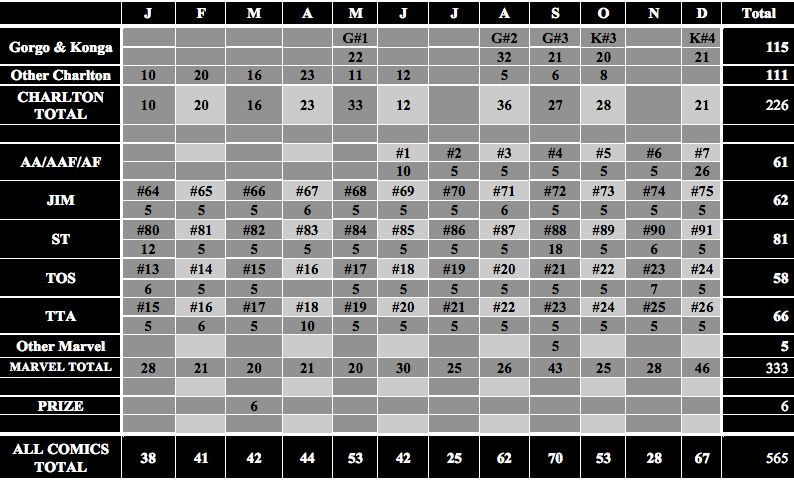

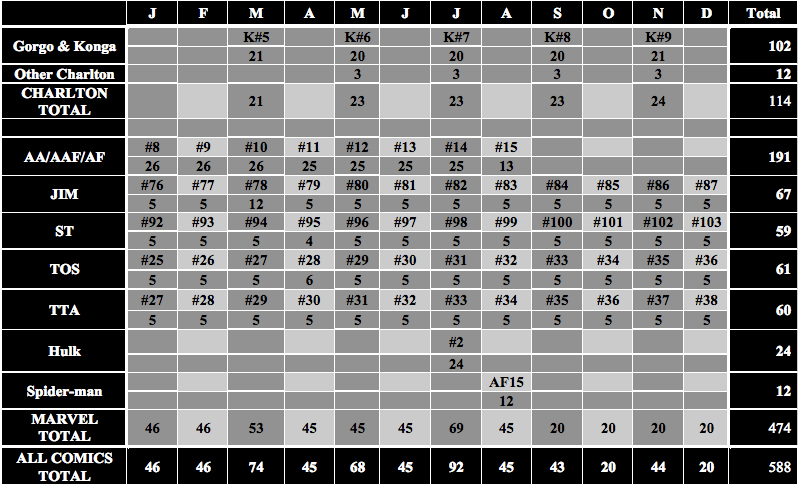

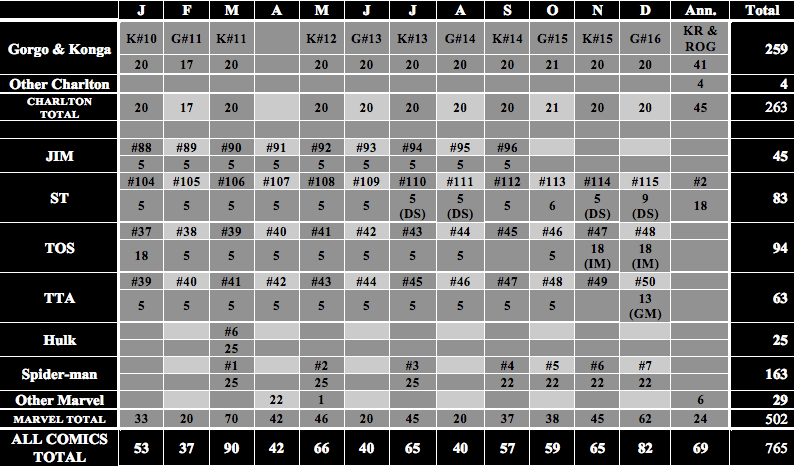

Once Spider-man had hit the stands it was inevitable that Ditko would become increasingly involved at Marvel and so, although 1963 saw an increased output by Ditko on Konga and Gorgo, Spider-man was developing and becoming monthly, and Ditko’s new creation, Doctor Strange in Strange Tales, meant that Marvel would occupy more of his time. Ditko’s involvement with Charlton (and the monster books) subsequently took a hiatus, until creative disagreements with Stan Lee at Marvel resulted in Ditko’s return to Charlton in 1966, but by then the monster movie comics were all but extinct. Ditko contributed a cover and two new short stories to a large 25c book, Fantastic Giants #24, which contained reprints of Konga #1 and Gorgo #1. Tables A1 through A3 summarize Ditko’s page output during the years 1961 through 1963, and the details are further condensed into graphs (Figures 2 through 4). The information contained within the tables and graphs is adapted from Bell (1998), with annual page output recalculated from Bell’s lists of Ditko-drawn stories. Pages inked by Ditko but drawn by another artist (usually Jack Kirby at Atlas) are counted as Ditko output. There are few stories or covers that fall into this category. Charlton covers composed of interior pages or panels drawn by Ditko are not counted, since Ditko did not have to re-draw the pictures for these purposes. Keeping in mind his very elevated status as a creative force in sequential art, this data on Steve Ditko’s work output during these early 60s years illustrates how important the Charlton monster books were to the artist by virtue of the fact that he continued to work on them, and increased his work on them, even while his work at Marvel was rapidly gaining momentum.

Figure 2. Breakdown of Steve Ditko’s page output, based on publication dates, in 1961. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 3. Breakdown of Steve Ditko’s page output, based on publication dates, in 1962. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 4. Breakdown of Steve Ditko’s page output, based on publication dates, in 1963. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Ditko appeared to have enjoyed drawing Konga and Gorgo as much as Joe Gill enjoyed writing the stories. Ditko seems to have a had a good relationship with Charlton and liked working with Gill, and even states that Gill may have been partly responsible for his long stay at that company (Ditko 1992). Ditko’s respect for Gill is clear – he considered Gill to be the best comic book story/script writer (Ditko 1992) seemingly not just because of the man’s ability to produce copious amounts of work, but because the scripts themselves were good. Gill stated that he gave the artists complete typed scripts with notes explaining what was going on in each panel, still leaving the artist as much freedom as possible, and without putting too much in each panel (J. Gill, personal communication, December 28, 2005). Gill also considered that he and Ditko were good friends, and described the artist as a principled person who produced just as good quality work for Charlton as he did for Marvel, despite the lower pay at the Connecticut company (Cooke & Irving 2000; Amash 2006; Bell 2008).

Charlton was a company formed by the alliance of Italian immigrant and entrepreneur John Santangelo, and disbarred attorney Edward Levy, after the two met while incarcerated in New Haven County Jail (Cooke & Irving 2000). Charlton’s main product initially was song books. After Charlton started printing comic books, Joe Gill, close friend of novelist Mickey Spillane and already an established comic book writer, was offered work at the Connecticut company when one of Santangelo’s editors found him driving trucks in Brooklyn (J. Gill, personal communication, December 28, 2005). Gill and Ditko were thrown together in Derby, staying in the one seedy hotel and discussing their work in the local bar. According to Gill, “Ditko and I were drinking buddies for a while, even though he wasn’t a drinker…we were totally unalike, we had nothing in common. But we hung out together” (Amash 2006, p.12). From Gill’s descriptions of conditions in Derby in the mid-fifties, one can only marvel at the way he and the artists who worked with him managed to meet deadlines and continue to produce reading materials for years on end. Gill was initially paid $4 per page at Charlton, but after the flood of mid-August 1955 that threatened to close down the company altogether, things got worse and took years to recover. After closing temporarily and salvaging whatever possible, Santangelo called his employees to a meeting and told them that they could continue operating if they all agreed to their pay being cut in half (J. Gill, personal communication, December 28, 2005). For Gill this meant $2 a page, and for the next 15 years there was only a 25 cent annual increment. The low rates meant that Gill had to have a considerable work output to meet his financial needs – he had to write a lot just to survive.

Despite having to maintain a high output simply to pay the bills, Gill’s work has enduring artistic and socio-political relevance. Joe Gill, down-to-earth and lacking pretense, worked hard at what he liked to do, which was writing to entertain people, and people who were entertained by his writing would buy more of his comics. Although Charlton was always overshadowed by EC and DC, and then Marvel, it was a company that produced a large number of titles over a considerable number of years, yet it has only recently begun to receive the recognition it deserved. It was a major company, for whom many of the industry’s greats worked; a company that survived the industry crash following the moral campaign against comics, and the introduction of content regulation and the Comics Code, and one that also continued beyond the changes that took place at the end of the 1960s, when superheroes were suddenly no longer so popular and other genres had to be explored to keep the industry momentum going. Charlton was in a good position to do this because it had always produced a wide variety of comic books. Gill was, then, a great writer in the comic book field, who, especially when he was allowed the luxury of time, could produce a work of excellent quality. In terms of inspiration, Gill commented that he had been an avid reader all his life, constantly devouring large quantities of paperbacks (J. Gill, personal communication, December 28, 2005). This, and a very active mind (Gill stated that it never stopped working), enabled him to just put a sheet of paper in the typewriter and start writing – he was never short of ideas. Gill’s reprocessing of other popular media content through his voluminous writings makes his work a useful source of information about themes that resonated with the minds of people in 1950s and 1960s America. Thus Gill acted partly as a largely passive provider of social commentary, his senses being the people who produced other popular media – movies, novels, television programs – which he then recycled into comic book stories. Gill also clearly had his own agenda, with his own political leanings. While predictably he was outspoken against communism, there are also glimpses of a more liberal mind, making statements that identify him as someone in favor of racial harmony, opposed to nuclear weapons, and concerned about the environment.

While Ditko’s own work on Konga and Gorgo compares well with his other work from the same time period in terms of artistic quality, there appears to be something of a difference in the way Ditko contributed to the Charlton monster stories compared with the method of story construction at Marvel. Stan Lee used a collaborative approach to story composition, that involved the artists as co-creators (Fischer 2004). This left a legacy of controversy over who actually created Spider-man and the other multi-million dollar Marvel characters (Raphael & Spurgeon 2003). At Charlton, Joe Gill provided complete scripts for all his stories, including the adaptations of Konga and Gorgo, and as Steve Ditko recalled: "I read the screenplay of Gorgo. From the first reading to this day, I marvel at how well Joe adapted the character to comic books. I didn't read the Konga screenplay but that comic script was (also) a treat" (Ditko 1992).

In fact Steve Ditko’s career supports the notion that he did not tend to work on projects that did not interest him, and Joe Gill observed that Ditko always did things the Ditko way (Cooke & Irving 2000). As an acknowledged master in the field of comic book art, Ditko’s dedication to the Charlton monster movie comics therefore suggests that these comics are worthy of greater attention than they have been accorded previously. Ditko’s contribution to these books, for which, as mentioned above, complete scripts were provided by Joe Gill, was to add his own interpretations and embellishments through the use of his art. Ditko is well-known for the use of hand gestures in giving his characters the ability to communicate non-verbally to the reader (Randall 2004) but examination of large quantities of his work reveals that he also uses body language and facial expressions constantly and very competently for the same purpose (Figures 5 through 10). This is indeed a feature afforded by the comic book medium, and is discussed, in relation to the non-human and largely non-speaking characters of the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote in Loony Toons cartoons and comic books, by Taylor (2001). In the case of the Charlton monster books this aspect of sequential art was especially significant because the lead characters are also non-speaking and non-human. Konga, however, being an intelligent ape and close to human from an evolutionary standpoint, allowed Ditko to use his skills in this particular area to give the simian the ability to communicate extensively and with greater effect, not only with the reader but also with the supporting human characters in the story. Ditko does this so well that it doesn’t matter that Konga can’t say anything. The look on his face tells the reader when he is angry, hurt, confused, sad, embarrassed, or in love. Montes and Bache also incorporated similarly extensive use of the great ape’s facial expressions in their own very beautiful and distinctive renderings for the Konga books. Reptilicus/Reptisaurus received no input from Ditko, but Montes and Bache perhaps reached the artistic pinnacle of their joint career in comics with the later issues of this series (Figure 11).

Figure 5. An unscrupulous face, from Gorgo #3: The Return of Gorgo, page 10, panel 5 (1961). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 6. A young lady in a ‘huff’, from Gorgo #13: Gorgo Captured, page 11, panel 3 (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 7: Fear and panic, from Gorgo #13: Gorgo Captured, page15, panel 3 (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 8. Annoyance on this woman’s face from Gorgo #16: Menace from the Deep, page18, panel 1 (1963). Art by Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 9. Fear and submission from Gorgo #3: The Return of Gorgo, p.10, panel 3 (1961). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 10. Konga’s no monster but a loveable goofball in Konga #15: The Evil Eye, page 5, panel 4 (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 11. An expedition locates their lizard quarry in Reptisaurus #7: Reptisaurus Returns, page 12, panel 4 (1962). The beautifully rendered artwork is by Bill Montes and Ernie Bache. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Konga, Gorgo, and Reptilicus: B-rate Monster Movies

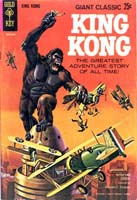

The original King Kong starring Faye Wray hit the screens in 1933 but Gojira (Godzilla) was first released in Japan in 1954, over 20 years later. Surprisingly there were no comic book adaptations of either until after Charlton had produced their own versions of the King Kong and Godzilla movie clones, the original giant ape taking graphic art form in Gold Key’s Movie Comics 30036-809 with a September 1968 publication date (Figure 12).

Figure 12. King Kong #30036-809 (Gold Key, September 1968). Copyright respective copyright holder. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

While the character of Konga is deliberately similar to King Kong (the movie posters claim “Not since “King Kong” has the screen exploded with such mighty fury and spectacle” – see Figure 13) the details of the stories differ somewhat. King Kong is found in his natural habitat by a Hollywood team out to shoot a movie, but Konga is the London laboratory creation of mad scientist and famous English botanist Charles Decker, experimenting with a growth serum derived from carnivorous plants he discovered when his plane crashed in Africa (Figures 14 & 15).

Figure 13. Konga lobby card (Copyright American International Pictures, 1961). [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 14. Decker’s plane goes down in the jungle. Konga #1: Konga, p.3, panel 3 (1960). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 15. First contact between Decker and Konga: Konga #1: Konga, p.5, panel 1 (1960). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

King Kong’s battle with aircraft while he is atop the Empire State Building in New York is mirrored (poorly) by Konga’s encounter with forces in London. In both movies one could view the giant ape as representative of nature in its primeval state, eventually overcome and destroyed by the ambitions or creations of man. Konga is more mindless than King Kong in the movie, and there is no real counterpart of King Kong’s attraction for Faye Wray in the Konga picture, although much is made of this theme by Gill in Charlton’s comic book series based on the Konga film.

Gojira (Godzilla) is an ancient giant reptile resurrected by undersea nuclear testing, and is variously interpreted as representing the atomic weapon (Benton 2004; Roberto 1997) or the US bombardment of Tokyo (Miller 1999), with the original Godzilla movie being an allegorical re-enactment of World War II. Gorgo, on the other hand, is reawakened by an underwater volcanic eruption in the North Atlantic, while Reptilicus regenerates from a piece of frozen prehistoric giant lizard tail that is recovered during some drilling in the Lapland tundra. The first lays waste to central London and the latter does the same to Copenhagen, but neither clone movie can claim to pursue an anti-nuclear ethic. Unlike Gojira, the two ‘B’ rate clones seek the monster movie thrills and little else. However, according to Berger, who references Ernest Dichter’s The Strategy of Desire, comic book monsters represent an out-of-control externalization of certain inner aspects of humanity that relate to the use of force and power (Berger 1973: 200).

Charlton Comics’ Monster Movie Adaptations

Gill appears to have made some changes to the Konga script as he adapted it for the comic book, at least if the comic is compared to the actual movie. In the movie Dr. Decker, the scientist, seems to be living with Margaret, his assistant, and only agrees to marry her in the future when she discovers he has been using Konga to eliminate his enemies. In Gill’s version, Decker and Margaret are already married. In the movie Decker is attracted to his student, Sandra, and has Konga eliminate Sandra’s protective boyfriend, Bob, out of jealousy and revenge. Decker’s influence over Konga in the movie stems from a mind-control additive to the enlarging formula, and his use of Konga as a hit man is conscious. In Gill’s Konga #1 Decker only inadvertently sends Konga on murder missions. This happens when he thinks negative thoughts about his competitor Dr. Tagore and Sandra’s boyfriend Bob (Figure 16) who, in the comic, only irritates Decker because he asks Sandra to marry him and she accepts, acknowledging that this will mean the end of her work as Decker’s assistant.

Figure 16. Decker runs to save Bob in Joe Gill’s comic book adaptation of the movie, as he realizes Konga must have been responding to his negative thoughts by killing the people Decker was thinking about. In the actual movie Decker deliberately sets Konga off on his missions of murder. The illustration is panel 6 on p.19 of Konga #1: Konga (1961), by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Thus, in Gill’s comic book version, Decker has become an unfortunate but basically good scientist whose downfall results from tampering with nature. In the movie he is endowed with a madness that is far more sinister, and his relationships with the two leading women bear testament to his lack of moral principles. Whereas in the movie Decker gets what he deserves, in the comic book Decker’s demise is somewhat more tragic. Gill’s changes were probably related to the need to satisfy the Comics Code Authority (see Nyberg, 1998 for a comprehensive treatise on the history of the Comics Code), but they also had the added benefit of setting up the scenario for the development of Konga into a series using Bob and Sandra as the creators of a second Konga – in the movie Sandra (swallowed by a carnivorous plant) and Bob (killed by Konga) both die before the end of the movie, but in Gill’s Konga #1 comic book (Figure 17) they survive. In the movie there is little actual destruction of London shown but in the comic book Ditko depicts far more extensive demolition – at that time comic books had a distinct advantage over movies in that they could illustrate graphically things that were extremely difficult or impossible to portray believably on screen. The movie also only has police and some infantry arrayed against Konga, shooting bullets and anti-aircraft rounds at the behemoth. In the comic Ditko has air force jets and tanks pounding the monster. In the end, though, Konga falls in both versions.

Figure 17. The cover of Konga #1 (Charlton Comics, 1960). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Gill’s subsequent Konga stories, as mentioned above, begin with Bob and Sandra recreating Decker’s formula and experimenting on another chimp, who then becomes the new Konga. With issue 12, however, Gill merges the ‘new’ Konga with the ‘old’, effectively re-writing the ending of the original movie adaptation to one in which Decker but not Konga dies, and the giant ape instead begins to experience his oft-repeated persecution at the hands of Earth’s military forces, the series running for a total of 23 issues and 3 specials.

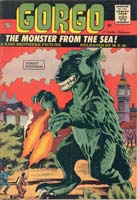

Gorgo #1 and Reptilicus #1 (Figures 18 & 19) both adhere more closely to the movie versions they are adapting. Figures 20 & 21 illustrate the cohesion between the screen and comic book versions of Gorgo. In the case of Reptilicus, however, the comic book contains little hint of the Copenhagen tourism sequences, the frequent scenes with the actual populace of the city running backwards and forwards in blind panic, and the stock military footage of tank maneuvers, that serve as fillers in the movie. Picking up the story from the endings of both these movies was a relatively easy task for Gill. Gorgo and his mother had returned to the sea after destroying London, and a piece of Reptilicus was left floating in the ocean, his pre-established capability for regeneration the key to continuing that saga.

Figure 18. The cover of Gorgo #1 (Charlton Comics, 1961). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 19. The cover of Reptilicus #1 (Charlton comics, 1961). Art by Rocco Mastroserio. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 20. In this Gorgo still from the 1961 movie the bathyscaphe encounters the monster. Copyright respective copyright holder. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 21. Joe Gill’s version of the bathyscaphe-Gorgo encounter. Art from Gorgo #1: Gorgo, p.14, panel 4 (1961) by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

In both the Gorgo and Reptilicus comic book series the monsters transform from destructive enemies of humankind into its saviors, often persecuted by those same entities they inadvertently rescue from other monsters or alien invaders. Gill utilized the same popular themes in these books as he did with Konga.

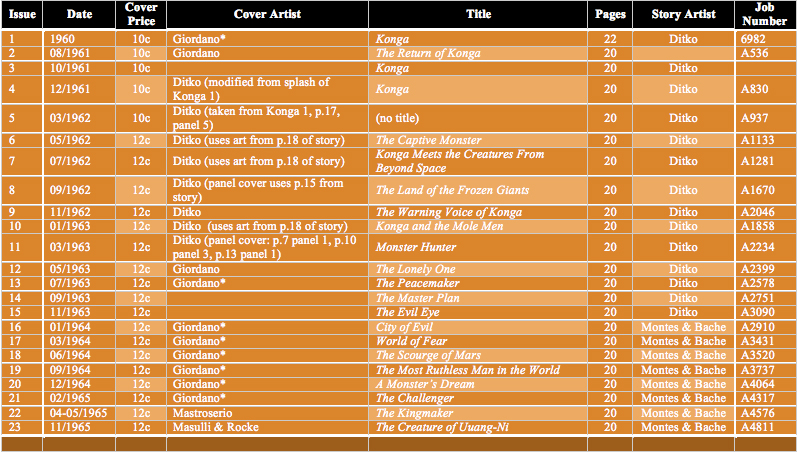

Tables B1 through B7 summarize the three Charlton monster movie series in terms of contributing artists and other details. In a number of cases the cover and/or story art is not signed, and identifications based on style have been made on some of these pieces of work by Ramon Schenk, contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine (R. Schenk, personal communication, November 21, 2005). In other cases Mr. Schenk has identified the creator of the art from the personal notebook of Joe Sinnott, through communication with the artist’s family. Sinnott worked on these series and recorded details referring to specific job numbers. Although some of the art nevertheless remains unidentified, these tables represent the most complete, comprehensive, and accurate accumulation of this type of information on these three titles that is currently available.

Gill’s Themes

Upon reading all of the Konga, Gorgo, and Reptilicus/Reptisaurus comics, certain themes emerge repeatedly. Some reflect the propaganda and political sensitivities of the Cold War period, and reinforce the ideology upon which the United States was founded. Others, while on the surface examining potential reactions to visitors from outer space, speak of cultural ambivalence in the United States at the time, with the Civil Rights Movement gaining momentum and the road to the resolution and acceptance of cultural differences beginning in earnest. The principle themes present in the monster movie adaptation stories are briefly recognized here, but each is worthy of comprehensive analysis in the context of the complete range of comic books published during the period in question.

Political Themes

Gill’s politics are staunchly American, in tune with the prevailing norms of the period. Gill’s value system is aligned against dictators and despots, in the mood of America’s founding fathers. If Nazis appear, there is no question that they are the bad guys, and with Gill’s proximity to World War II, this is also to be expected. The contemporary threat of communism is particularly noticeable. Overall Gill’s stance is strongly patriotic.

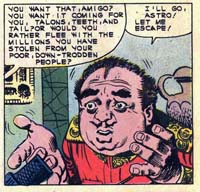

Anti-communism

Written at the height of the Cold War, the Charlton monster movie books by Joe Gill are replete with scenarios in which the free world is threatened by the totalitarian ideology and world domination-seeking forces of communism, represented by both the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, and by smaller countries being subjected to the influence of these giants. Stereotypes are abundant, as exemplified by Figure 22. Soviet premier Nikita Khruschev features in several stories, one of which specifically refers to the Cuban Missile Crisis (Figure 23). The communists usually assume that the monsters who are thwarting their attempts to attack the west are under the control of the capitalists. This theme more or less constitutes raw anti-communist propaganda, but some comics even contained actual single page propaganda items separate from the monster story. Gorgo #14 contained Strength of a Nation, which extolled the virtues of living in freedom, while Konga #9 and Reptilicus #6 featured different episodes in the series Your Role in the Cold War. Besides the arms race, other Cold War sub-plots include the space race and espionage. Monster stories with an anti-communist theme appeared in Konga #9, #12, #14, #15, and #20, Return of Konga (no number), Gorgo #7, #9, #13, #14, #17, #20, #21, and #22, Gorgo’s Revenge (no number), and Reptisaurus #5, #6, and #7.

Figure 22. A rotund Soviet official threatens his general with a post in a harsh environment unless he stops Konga from interfering with their plans to gain superiority over the West. The art, by Steve Ditko, is from Konga #9: The Warning, page 11, panels 1 & 2 (1962). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 23. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet premiere Nikita Khrushchev wage war with words during the Cuban Missile Crisis in Gorgo #14: Deadlier Than Man, page 12, panels 5 & 6 (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Anti-tyranny

A number of stories feature tyrannical dictators of small countries usually populated by masses of the poor. The dictators invariably have desires to conquer their neighbors as a step towards world domination. These megalomaniacs tend to come unstuck when their over-ambitious plans bring them into contact with a giant ape or lizard. This theme was used in Konga #14, #19, and #22, and in Gorgo #3.

Return of the Third Reich

The proximity to World War II of the early 1960s and the uncertainty as to the whereabouts of all the Nazis, even including doubts as to whether Hitler really died in the bunker, allowed writers to speculate regarding possible resurgences of the Third Reich. Joe Gill uses this theme in Konga #4 (1961) in which Adolf Hitler, having escaped from Berlin at the end of the war, is finally brought to justice as the giant ape sinks his submarine (Figure 24).

Figure 24. Adolf Hitler finally meets his demise at the hands of Konga when his submarine is sunk by the giant ape in Konga #4: Konga, page 20, panel 1 (1961). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Issues of Difference

The frequent use of alien invaders as antagonists in the Charlton monster movie books reveals two aspects of the collective consciousness of the time. The first is the genuine concern with the possibility of life elsewhere in the universe that accompanied our first steps into space. The second involves aliens from other planets as analogous to aliens from other countries coming to the United States.

Alien Invasion

The panic resulting from the Orson Welles radio adaptation of the H.G. Wells classic, War of the Worlds (“Radio Listeners,” 1938), and the mystery and rumors surrounding the alleged Roswell flying saucer crash in 1947 certainly contributed to the public’s sense of wonderment as to whether or not we are alone in the universe. “Are we alone?” is, in fact, a question that can only have two answers: “maybe” and “no”, since we cannot hope to investigate the entire universe to prove that life is unique to Earth, and if we do contact extra-terrestrial life then that would settle the issue. The more we learn about the universe the more this question comes to the fore. So aliens arriving from other planets in our solar system or from elsewhere in space then pose the next question: if they are stronger and more technologically advanced than us, and they are malevolent, who will protect us from them? Will we be able to survive the encounter? In some cases Gill even uses the idea that there are alien races right here on Earth, either underground (Konga #10, 1963) or from the lost city of Atlantis (Gorgo #6, 1962). Overall Gill employs this theme a number of times in the monster movie books (see Figure 25), with Konga, Gorgo, and Reptisaurus becoming the guardians of the human race in a sort of modern-day mythology, in which we, the human race, seem to reach out in search of higher or more powerful beings who will watch over us when we are finally confronted with a foe we cannot defend ourselves against. This popular theme was employed in Konga #7, #10, #13, #16, #18, and #21, Gorgo #10, #12, and #18, The Return of Gorgo #2, and Reptisaurus #3.

Figure 25. Fortunately for Planet Earth, these hostile aliens made the mistake of landing on the island that Konga had made his home in Konga #7: Konga Meets the Creatures from Beyond Space, page 9, panel 4. Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Xenophobia and Persecution of Those Different From Us

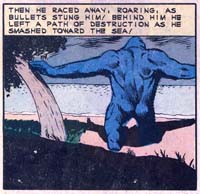

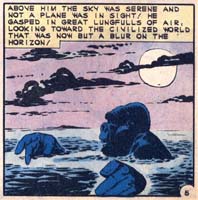

This is also a fundamental theme running through all of these monster books. All three monster protagonists evolve into benign or even beneficent entities under Gill’s supervision, but they are invariably misunderstood by the vast bulk of humanity and hounded by the military wherever they go. Konga is especially torn by this circumstance, since all he wants really is a loving relationship with humans, like that which he enjoyed when he was just a small laboratory monkey in Bob and Sandra’s care. Instead he usually finds himself seeking solitude in remote places away from civilization (see the sequence of five panels from Konga #7 in Figure 26).

Figure 26. The direction given to Konga by Joe Gill was one of lonely persecution, exemplified by this sequence of five panels from Konga #7: Konga Meets the Creatures from Beyond Space, page 4 panels 3 and 4, page 5 panels 3 and 4, and page 6 panel 1. Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE]

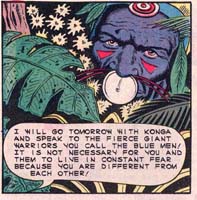

Direct reference to the Civil Rights Movement is conspicuous by its absence, but this is in no way unusual for early 1960s comic books. Such issues did not come to the fore in comics until the mid- to late 1960s. The focus was still very much on external threats such as the spread of communism. However, in Konga #17 Gill uses two warring tribal groups to discuss fear of others based on physical and behavioral differences (see Figure 27). The story promotes the idea of racial harmony, and even introduces the concept of reincarnation, a very eastern philosophical idea. In fact, criticism of the unthinking barbarism of the so-called civilized world surfaces here and there in Gill’s monster book writings: “the civilized world of man was even worse than the jungle where the law of tooth and claw had always prevailed” (from the introduction to Konga #17). Gill promotes the analysis that killing comes from hate, which arises from fear, in this case of people who are different.

Figure 27. Joe Gill promotes the notion of racial harmony. A blind hermit rescued by Konga acts as an intermediary between two racially different tribes, and sacrifices his life in the cause. As the hermit is dying he reassures us that, having “lived many, many lives,” he is not afraid of what lies beyond death’s veil, a rare reference to reincarnation in 1960s comic books. Art by Bill Montes and Ernie Bache from Konga #17: World of Fear, page 17, panel 1 (1964). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

The Scientific Age

The 1950s and 60s were decades of world transforming scientific advancement. The scientist became the new advisor, the new priest, the new authority to whom all turned. Gill’s stories bring out the ambivalence and hesitancy the public held towards science, on the one hand marveling at boundaries being pushed back on all fronts, but on the other inwardly concerned as to where this was all leading.

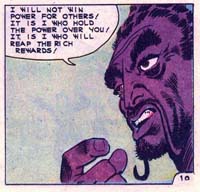

The Madness of Science

Mad scientists abound in these monster movie stories, usually with plans to gain control of one of the creatures and use them for their own ends. Science, the new mysticism, is seen as out of reach of the ordinary person, giving the scientist some kind of assumed authority over the rest of the world. Steve Ditko excels in drawing this kind of character (Figure 28), and they always come down to Earth in the end because they have such tunnel vision (Figure 29). Mad scientists were the stuff of Konga #15, The Return of Konga (no number), Gorgo #3 and #19, and Reptisaurus #8.

Figure 28. Mad scientist, Steve Ditko style, from Konga #15: The Evil Eye, page 2, panel 2 (1963). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 29. Another crazy scientist meets his demise in Reptisaurus #8: Brood of the Beast, page 19, panel 1 (1962), drawn by Bill Montes and inked by Ernie Bache. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

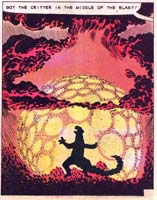

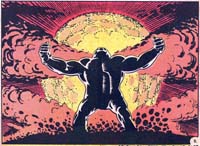

Nuclear Weapons and Testing

This is a major theme running through all three series. The comics sometimes border on making strong political statements warning of the dangers of nuclear tests (usually under the sea or on a Pacific island) and reflect a popular concern of those times. Gill created the superhero character Captain Atom in 1959 as an air force man transformed by the radiation from a nuclear explosion. During the 1960s Stan Lee used the radiation origin story in various forms for a number of his heroes, for example, the Fantastic Four (exposed to cosmic radiation), Spider-man (bitten by radioactive spider), the Incredible Hulk (Bruce Banner is irradiated during a nuclear bomb test), and so on. Gill’s giant monsters are, however, relatively impervious to nuclear weapons, and survive a number of explosions (see Figures 30 and 31). In Konga #10 Gill even introduces a subterranean race of beings who were once surface dwellers in Earth’s distant past. They had a highly developed civilization but destroyed it all in a nuclear war, the survivors retreating and then evolving underground. Nuclear weapons or testing appeared in some form in Konga #5, #10, #11, #13, and #20, Gorgo #2, #4, #5, #9, #16, and #17, Return of Gorgo #2, and Reptisaurus #8.

Figure 30. Gorgo’s mother takes a direct hit from a nuclear bomb as half of New York is sacrificed in the process, in Gorgo #2: Gorgo Returns, page 23, panel 4 (1961). Art by Steve Ditko. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 31. A resplendent Konga takes the best that the trigger-happy human race can dish out in Konga #8: The Land of the Frozen Giants, page 3, panel 3 (1962). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

The Environment

That an early 1960s comic book (Konga #10, see Figure 32) can make a comment about the destruction of the natural world by the activities of man is somewhat unusual and shows that Joe Gill was not merely the ‘capable hack’ that he describes himself as (Irving 2000) but a writer who was tuned in to the cutting edge issues of the day. For perspective, it should be noted that Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published in September 1962, marking the beginning of the Environmental Movement. With its publication date of January 1963 (see Table B1), Konga #10 would most certainly have been on the stands in October or November of 1962, and was likely written around or even before the publication date of Silent Spring.

Figure 32. Joe Gill’s awareness of the environmental damage wrought by the activities of western civilization on the planet leaks out in panel 1 from page 11 of Konga #10: Konga and the Mole Men (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Romance

This major theme runs through virtually all of these monster books as a sub-plot. Not all the scientists are mad. In fact most of the lead supporting characters are reasonably sane scientists often accompanied by (if they are older gentlemen) their daughters (who invariably fall in love with a young man who is helping their father), their girl friends (whom they end up marrying after the two are brought closer together during their harrowing adventure), or their female assistants (whom they end up falling in love with and marrying). Explorers or film-makers are sometimes substituted for scientists, and all may be already married or in relationships, and take their wives or fiancées with them on their monster hunts. By using a number of different sub-plots Gill created stories that would appeal to a wider audience. In the 1960s there were still large numbers of girls who read romance comics, so having a romantic element in the story might attract this readership. On the other hand a monster comic would be a good place to put a romantic theme that boys could enjoy reading without being seen carrying a copy of Girls’ Love Stories. The issues drawn by Joe Sinnott and inked by veteran romance artist Vince Colletta (or by his assistants in the ‘Colletta Shop’) have a real romance comic feel in parts (Figure 33). The romantic twists could get quite intricate (see the sequence of three panels in Figure 34) but there was always a happy ending (Figure 35).

Figure 33. Romance artist Vince Colletta’s distinctive touch is evident in the inking of panel 1 from page 8 of Gorgo #8: The Graveyard of Lost Ships (1962). Pencil art by Joe Sinnott. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Figure 34. In this romantic sub-plot, Helen had been thinking of leaving Phil, but the way she saw her husband respond to their crisis in Cuba showed her a side of him she hadn’t seen before. Her doubts were overcome and her love for her husband rekindled. Sequence of three panels from Gorgo #14: Deadlier Than Man, page 9, panel 2, and page 13, panels 2 and 3 (1963). Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE]

Figure 35. Reptisaurus #8: Brood of the Beast concludes with two blissful lovers looking forward to their lives together. Page 20, panels 3 and 4, artwork by Bill Montes and Ernie Bache. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Humor

Joe Gill’s stories often have an undercurrent of humor that surfaces at different points, especially in those books illustrated by Steve Ditko. Figure 36 is typical of the zany asides added to lighten up the plot. Certain books, for example Gorgo #11 and Konga’s Revenge #2, have a very strong humorous component.

Figure 36. Joe Gill, in conjunction with artist Steve Ditko, was fond of interjecting a little humor into his monster stories, as in these two panels (3 and 4) from Konga #12: The Lonely One, page 2 (1963). Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Fear of Forces Beyond Our Control

Blind Panic

Where there are giant monsters in cities, there are hoards of people in states of total panic, no better exemplified than by the cover of Konga #6 from 1962 (Figure 37).

Figure 37. Scenes of crowds fleeing in fearful panic from a giant monster, such as this one on the cover of Konga #6 (1962), were more typical of Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby’s work on the fantasy books at Atlas (Marvel) of around the same time period. Art by Steve Ditko. This cover is an example that re-uses interior art from the story to create the cover, for the purpose of economy. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Monster vs. Monster

In true King Kong vs. Godzilla tradition, Joe Gill uses the spectacle afforded by a clash of the titans, while helpless humans fearfully await the outcome, as the story line in several of his monster comics. The monsters may be lurking in volcanoes as in Konga #23, released by a nuclear explosion from ages-long imprisonment beneath the ocean floor as in Gorgo #5, or trapped in a world that time forgot beneath the Antarctic ice as in Konga #8. Sometimes the visiting aliens from outer space are gigantic monsters, such as the Venusian terrors in Gorgo #10. In all this theme was used in Konga #2, #3, #8, and #23, and Gorgo #5, #6, #10, #15, and #23.

Popular Consciousness of the Early 1960s in America

Taken as a whole, the themes used by Joe Gill for his monster stories tell us a great deal about the thoughts and fears that occupied the minds of the average American during the early 1960s. According to some, the therapeutic transformation of the Japanese fear of the nuclear bomb into the monster Gojira allowed the disturbing memories of the nuclear holocaust to be tamed (Billson 1996). Popular media in general could be argued to be carrying out this same subtle function of allowing society to process its deepest fears. The uncertainties arising from the “Are we alone?” question and others like it (“Are our enemies stronger than us?”, “Who will protect us?”, “What will happen if there’s a nuclear war?”, “What are these scientists doing to us?”, “Will I find true love?”, etc.) become, at least temporarily, assuaged by externalization and repetition through literature, movies, comic books, or any other kind of entertainment media. Joe Gill, by his own admission, was a major consumer of popular entertainment in the form of paperback novels (J. Gill, personal communication, December 28, 2005), and so it is natural that the mass of ideas that was floating around inside his head would re-emerge in his writing, reprocessing those same barely subconscious societal fears in his comic books, offering us an insight into the American mindset of the period.

Final Word

The Charlton monster movie comics of writer Joe Gill, taken as a body of work, represent a time capsule of revealing information not only about the society in which the comic books were conceived, but also of the process of comic book production in the early 1960s, a time when such forms of literature were a significant presence, particularly in the lives of young people. Especially they tell us details about the functioning of Charlton, a company that produced comic books, a very American form of popular media, during five decades in the mid- to late twentieth century. Charlton’s thrifty strategies for producing their books, such as re-using panels of interior art for the comic book cover (Figure 38), buying low quality paper and cheap inks (Irving 2000), printing covers on a press designed for cereal boxes (Frantz 2002), and paying their artists and writers low rates (Cooke & Irving 2000), when seen in the context of the struggle to survive in a highly competitive market, become quite admirable.

Figure 38. The cover of Gorgo #16 (1963) illustrates the way Charlton re-used interior art panels to construct a cover. The time taken to do this would be minimal compared to having an artist draw a cover from scratch. Art by Steve Ditko. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

DC and Marvel have been regularly producing archive editions of their earlier work, but because Charlton is an extinct company, there is very little available in the form of modern reprints for those interested in the Charlton material, and series such as the monster movie adaptations are in danger of disappearing as their 50-year-old pulp paper becomes fragile and turns to dust. Of these particular books only the Konga stories from issues 11, 12, and 13 have appeared in a black and white reprint edition entitled The Lonely One (Gill & Ditko 1989). As a piece of American cultural history of considerable artistic merit, the Charlton monster movie adaptations require fuller recognition than they have received to date (Figure 39).

Figure 39. Konga’s search seemed doomed to failure in a hostile world full of misunderstanding and fear in Konga #17: World of Fear, page 7, panel 2 (1964). Art by Bill Montes and Ernie Bache. Copyright Charlton Comics Group. [CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE]

Table A1. Steve Ditko: Published Pages 1961

Note. Abbreviations used in Table A1: AA = Amazing Adventures; AAF = Amazing Adult Fantasy; AF = Amazing Fantasy; G = Gorgo; JIM = Journey into Mystery; K = Konga; ST = Strange Tales; TOS = Tales of Suspense; TTA = Tales to Astonish.

Table A2. Steve Ditko: Published Pages 1962

Note. Abbreviations used in Table A2: AA = Amazing Adventures; AAF = Amazing Adult Fantasy; AF = Amazing Fantasy; JIM = Journey into Mystery; K = Konga; ST = Strange Tales; TOS = Tales of Suspense; TTA = Tales to Astonish.

Table A3. Steve Ditko: Published Pages 1963

Note. The following abbreviations are used in Table A3: Ann. = Annual; AA = Amazing Adventures; AAF = Amazing Adult Fantasy; AF = Amazing Fantasy; DS = Doctor Strange; G = Gorgo; GM = Giant Man; IM = Iron Man; JIM = Journey into Mystery; K = Konga; KR = Konga’s Revenge; ROG = Return of Gorgo; ST = Strange Tales; TOS = Tales of Suspense; TTA = Tales to Astonish.

Table B1. Konga

Note. Entries marked * indicate identification of artwork by Ramon Schenk, contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine.

Table B2. Fantastic Giants (numbering continues from Konga #23; reprints Konga #1 & Gorgo #1)

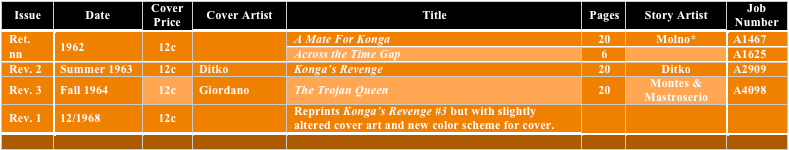

Table B3. Return of Konga and Konga’s Revenge

Note. Entries marked * indicate identification of artwork by Ramon Schenk, contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine. The following abbreviations are used in the table: nn = un-numbered issue; Ret. = Return of Konga; Rev. = Konga’s Revenge.

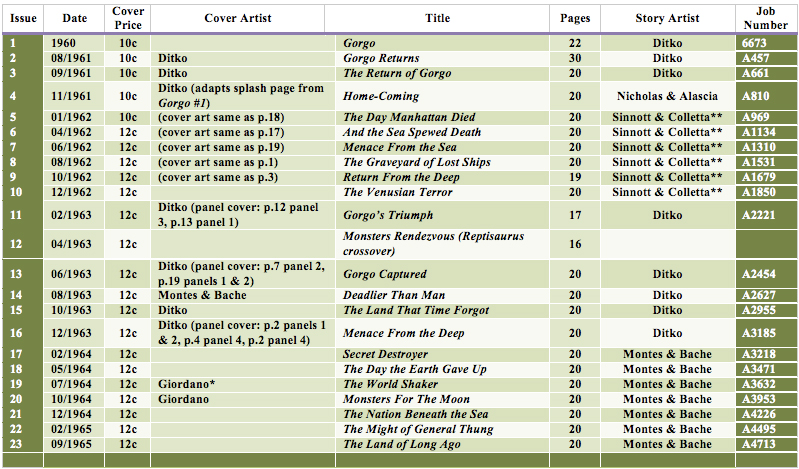

Table B4. Gorgo

Note. Entries marked * indicate identification of artwork by Ramon Schenk, contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine. Entries marked ** indicate identification by Ramon Schenk via communication with the family of artist Joe Sinnott.

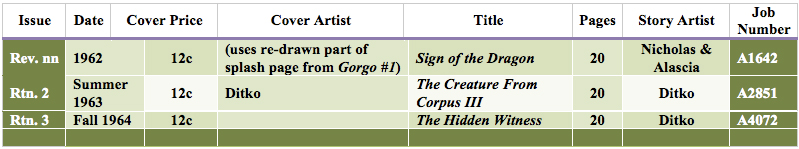

Table B5. Gorgo’s Revenge and Return of Gorgo

Note. Abbreviations used in this table: nn = un-numbered issue; Rtn. = Return of Gorgo; Rev. = Gorgo’s Revenge.

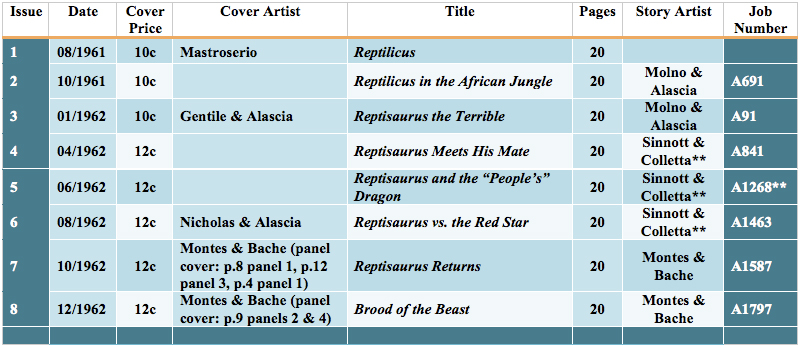

Table B6. Reptilicus (Reptisaurus #3 on)

Note. Entries marked ** indicate identification of artwork by Ramon Schenk, contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine, via communication with the family of artist Joe Sinnott.

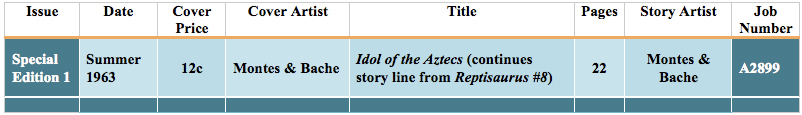

Table B7. Reptisaurus the Terrible Special Edition

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Joe Gill (1919-2006), a talent not fully recognized in his own time. He was kind enough to entertain me with his comic book stories when I was a child, and then to talk to me forty-five years later about his many years of work at Charlton Comics.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the following people for their advice and valuable assistance in the completion of this paper: the late Joe Gill (Seymour, Connecticut), writer of innumerable Charlton comics; Ramon Schenk (Rotterdam, The Netherlands), contributing editor of Charlton Spotlight magazine; Michael Ambrose (Austin, Texas), editor and publisher of Charlton Spotlight magazine; Nick Caputo of the Yahoo Ditko-Kirby discussion group. For those interested in reading further on the life of Joe Gill, the Fall 2006 issue of Charlton Spotlight magazine features a 24-page interview with the great writer by Jim Amash.

References

Amash, J. (2006) “The Joe Gill interview” in Charlton Spotlight 5: pp. 2-25

Anderson, C. (2004) “The Old Corral”, http://www.b-westerns.com/trio.htm, accessed February 14, 2008

Bell, B. (1998) “Ditko Looked Up”, http://www.ditko.comics.org/, accessed February 14, 2008

Bell, B. (2005) “Introduction: Steve Ditko and Marvel Comics”, pp. 5-6 in Marvel Visionaries: Steve Ditko, ed. M. D. Beazley, New York: Marvel Comics

Bell, B. (2008) Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books

Benton, G. (2004) “Gojira vs. Godzilla: The Original Allegorical Meaning of Godzilla and the Damage in the Americanization Process”, http://gojistomp.org/movies/documentary/godzresearchpaper.html, accessed December 4, 2005 [site no longer exists]

Berger, A. A. (1973) The Comic-Stripped American: What Dick Tracy, Blondie, Daddy Warbucks, and Charlie Brown Tell Us About Ourselves, New York: Walker

Billson, A. (1996) “Monster Movie” in New Statesman 127 (4394): pp. 39-40

Comic Book Gorillarama (2003) “Konga”, http://members.shaw.ca/gorillagallery/myweb2/konga.htm, accessed February 14, 2008

Cooke, J. B. & Irving, C. (2000) “The Charlton Empire: A Brief History of the Derby, Connecticut Publisher” in Comic Book Artist 9: pp. 14-21

Daniels, L. (1995) DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes, New York: Bullfinch (Little, Brown and Company).

Dark Horse Comics (2009) “Dark Horse Comics Company Timeline”, http://www.darkhorse.com/Company/Timeline, accessed March 23, 2009

Ditko, S. (1992) “First Choice”, in Robin Snyder's History of the Comics 3 (2): p. 31

Fischer, C. (2004) “Unmasking the Villain: Notes on Ditko, Kirby, and Marvel-style Plotting” in The Comics Journal 258: pp. 97-100

Frantz, R. (2002) “It’s a Long, Long Way to Derby” in Charlton Spotlight 2: pp. 6-13

Gill, J. & Ditko, S. (1989) The Lonely One, Bellingham, WA: Robin Snyder

Irving, C. (2000) “Joe “Mr. Prolific” Gill: The Phenomenally Productive Writer Speaks” in Comic Book Artist 9: 22-24

Lee, S. & Mair. G. (2002) Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, New York: Simon & Schuster

Miller, J. J. (2009) “The Comics Chronicles: A Resource for Comics Research”, http://www.comichron.com/, accessed March 28, 2009

Miller, T. (1999) “Struggling With Godzilla: Unraveling the Symbolism in Toho’s Sci/Fi Films” in Kaiju-Fan 10 (Winter): http://www.historyvortex.org/GodzillaSymbolism.html, accessed February 14, 2008

Nyberg, A. K. (1998) Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi

“Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact” in The New York Times (1938, October 31): p. 1

Randall, B. (2004) “Ditko’s Hands: An Appreciation” in The Comics Journal 258: 91-93

Raphael, J. & Spurgeon, T. (2003) Stan Lee and the rise and fall of the American comic book, Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press

Roberto, J. R. (1997) “Godzilla and the Second World War: A Study of the Allegorical Meaning in “Godzilla” and “Godzilla Raids Again” in Kaiju-Fan 5 (Spring): http://www.historyvortex.org/GodzillaSecondWorldWar.html, accessed February 14, 2008

Taylor, T. (2001) “If He Catches You, You’re Through: Coyotes and Visual Ethos” pp. 40-59 in The Language of Comics: Word and Image, ed. R. Varnum & C. T. Gibbons, Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi