Code-Breaking and Videogame Engrossment

Michael Skolnik

Abstract

Videogame code generates a virtual space governed by rules and mechanics that produce a range of moment-to-moment player experiences. Practices of play, labour, and reward are themselves designed and encoded into gameplay, and by extension, the player experience of it. When people play games, code arrests them, and involves them in the activity to different degrees at different points in time.

This article examines the relationship between these encoded cultural practices and the gameplay experience, through two case studies of gameplay segments that involve the player in code-breaking outside of the game world. Code-breaking functions as a metaphor, with these gameplay sequences challenging disciplinary assumptions, codes, and thought processes about games. These gameplay segments are a departure from the typical understanding of narrative-centric gameplay as diegetic work (us sinking time into playing in the game world) leading to diegetic reward (story/setting development, progression). While all gameplay is an engagement with code, puzzle-solving gameplay as a particular form of gameplay offers possibilities for different, challenging types of code-related engagement.

Through this analysis, this article makes the aesthetic argument that linking work outside of the game world with rewards inside the game world fosters a sense of engrossment (Goffman 1974), facilitates an enjoyable experience, and opens up new possibilities for games as an expressive medium with positive social outcomes. The article also argues for a holistic game criticism that takes into account the structure of work and reward, as well as the temporality of play based on micro-sociological accounts of gameplay (Deterding 2013).

Introduction

Videogames interpellate players into behavioural codes of play and hybrid player and character/avatar identities. This takes place on multiple levels; as the platform studies approach to game studies emphasises, pieces of gaming hardware such as consoles and controllers offer the player different affordances (Montfort & Bogost 2009). The game as a designed object composed of programming code structures the way that a player experiences the game’s rules, mechanics, narrative, and space. These interpellations are “insistent design invocations” which “hail players into particular roles and behaviours within a play context” (Ruggill & McAllister 2011: 34, see also Althusser 2008). These design invocations allow for play that is enjoyable despite the tedium and aimlessness that Judd Ruggill and Ken McAllister associate with videogame play (2011: 35). For example, ‘grinding’ in role-playing games (playing through repetitive and tedious gameplay segments to attain higher character levels and greater character power) is an insistent design invocation of this kind. The promise of playing the powerful questing hero later keeps players interested in spite of the fact that the player is playing the middling errand-runner now.

Play generally incorporates an element of work. Aarseth argues that interactive narratives, including narrative-oriented videogames, require “non-trivial effort […] to allow the reader to traverse the text” (1997: 1). This can also hold for non-narrative-oriented videogames, taking into account a range of possible tasks including mastering the controller interface, solving puzzles, powering through tedium, or engaging in the more delightful task of navigating compelling challenges. When this work is channelled into dealing with well-structured challenges with a reasonable difficulty curve, it can produce a desirable and enjoyable play-state, a flow-state (Csikszentmihalyi 1991) in which the player is motivated to keep playing to overcome the challenge.

This article examines two case studies, which centre on code-breaking as a game-play activity: the cipher puzzles in Assassin’s Creed II (Ubisoft 2009), and the protein-folding puzzles of Foldit (University of Washington 2008). These case studies position the work that the player undertakes in relation to the diegetic level (Prince 1987: 20) of the game’s action - drawing on Alexander Galloway’s use of diegesis (2006: 7-8). It does so in order to argue that the relationship between work and reward can offer different kinds of experiences with different political and aesthetic values, particularly in regard to narrative-centric games.

In this article, I argue that metadiegetic gameplay tasks, those “[p]ertaining to or part of a diegesis […] that is embedded in another one and, more particularly, in that of the primary narrative” (Prince 1987: 50), foster a desirable sense of engrossment; a condition involving the player oscillating between several different referential frames constantly, rather than identifying with the character in the game-world exclusively as with immersion (Goffman 1974; Fine 1983: 196, for immersion, see Murray 1997; Grau 2003). This gameplay structure is aesthetically desirable in video game design for entertainment purposes, allowing opportunities for deeper player involvement.

Games, work and reward

Generally, work and reward in narrative-centric games are considered on diegetic terms. Players work to progress through the story and are rewarded with plot development and new challenges in the game. If the game is well-made, these rewards and this new content delight them aesthetically. There are beautiful stories, challenges, worlds, characters, and experiences for players to encounter through play. Players’ work goes into the game’s world, and rewards manifest in it; this feedback loop continues until they stop playing. Diegetic work leads to diegetic reward. However, this is not the only relationship work and reward can have to diegetic level. The first case study illustrates the engrossing use of metadiegetic fiction puzzles. The second case study illustrates the complications of attempting this kind of analysis with non-narrative-centric games.

Engrossment and player involvement

Sebastian Deterding (2013) argues that formalist game studies are troubled by media convergence and instrumental play patterns that disrupt formalist assumptions about play. Deterding traces a history of player-centric, micro-sociological accounts of play being called for as a response to this problem, citing frame analysis (Goffman 1974) as the most used method for addressing it.

Frame analysis examines the different framings of events and experiences that people employ to understand social situations, for example, to discern when someone is joking, storytelling, or employing some particular kind of communicative act. Gary Alan Fine (1983: 182-196, see also Mackay 2001: 54) points to three such frames in relation to games, particularly role-playing games: the social frame (player-as-person), the game frame (player-as-player), and the game-world frame (player-as-avatar/character).

Fine, citing Goffman, argues that the constant need to shift between these frames during the course of play creates engrossment in the play activity:

Although perhaps contrary to common sense, people easily slip into and out of engrossment. Frames succeed each other with remarkable rapidity; in conversations, people slip and slide among frames. Engrossment, then, need not imply a permanent orientation toward experience. This point is consistent with Goffman’s discussion of talk as a “rapidly shifting stream of differently framed strips”. (Fine 1983: 182)

As a model for player involvement, engrossment carries some benefits over immersion (Murray 1997; Grau 2003), namely that critical distance is maintained and engrossment encompasses a number of gameplay-related practices that occur outside of play (strategic discussion, fan production, and so on; see McMahan 2003). More recent approaches to player involvement, such as Gordon Calleja’s notion of phenomenological incorporation (2011), are compatible with frame analysis and its engrossment-based approach. This article argues that the judicious use of metadiegetic elements in games – specifically puzzles in its case study games - fosters engrossment. The first case study explores this kind of metadiegetic puzzle-solving.

One alternate configuration of work and reward in relation to diegetic level is gamification; the layering of game-like elements on top of non-game tasks in order to make these tasks more compelling, which is an example of a possible set of Ruggill and MacAllister’s insistent design invocations. While numerous critiques of gamification have been made (well summarised in Rey 2012), particularly centring on gamification as a form of crude behaviourism or exploitation, for this article’s purposes, the focus of gamification is that it also employs a different structure of player work (per Aarseth) and reward - one where the work takes place outside of the game, and the rewards within. Advocates of gamification argue that this gameplay structure is more engaging and compelling for players (Zichermann 2011). The second case study also deals with this work/reward configuration.

Puzzle aesthetics

Veli-Matti Karhulahti’s “Puzzle Art in Story Worlds: Experience, Expression and Evaluation” (2012) examines the pragmatic aesthetics of puzzles with emphasis on diegetic fiction puzzles, which are “puzzles that are integrated to fictional story worlds […] in which stories take place” (2012: 2).

Karhulahti’s main argument is that puzzles, and especially fiction puzzles, are self-contained pieces of art with particular means of expression, and can produce and support aesthetic experiences in players who encounter them (Karhulahti 2012: 1). “[A] puzzle is indeed a small work of art that stimulates curiosity and provides a kind of aesthetic pleasure all its own” (Danesi in Karhulati 2012: 4). This argument borrows from John Dewey’s pragmatic aesthetics, which position art as residing in “aesthetic experiences that take the place of artworks” (Dewey in Karhulahti 2012: 2), and Phillip Deen’s application of pragmatic aesthetics to games (Deen 2011: online).

Karhulahti draws on Clara Fernández-Vara’s (2009) study of adventure game puzzles, to define a fiction puzzle as:

[A] mental challenge where there is no active opponent. It is integrated to a story world and there is usually a solution, which may be possible to obtain in more than one way. The solution entails insight and logical thinking, and it is attained by interacting with the story world primarily through a player character. (Karhulati 2012: 3)

While Karhulati positions a fiction puzzle’s integration into a fictional world as a yes/no proposition in the above quotation, there might be room to ask questions like “how integrated to a story world does a fiction puzzle have to be?” Or, in other words, “what diegetic level does it have to operate at?” Karhulahti seems to be aware of this, as, in the paragraph before this definition, he notes that fiction puzzles are only typically, but not always, solved through the direct control of a player character. For example, in the case of typing in a puzzle solution, the input is not directly a player character action, though it is representative of one (it is extradiegetic rather than diegetic). The solution might then be used in the player character’s speech to represent the character solving the puzzle, hypothetically. This seems to create a hierarchy of fiction puzzles in which those fiction puzzles solved through the direct control of a player character (either diegetic or mimetic) sit at the top, and in which those solved outside of the game by the player representatively (extradiegetic or metadiegetic) of the character sit below. Furthermore, this raises the possibility of more, different, kinds of player activity to play a role in fiction puzzles. In relation to the case studies, which are analysed in the next section, the code-breaking segment in Assassin’s Creed II is a possible example of a different kind of fiction puzzle. In it, the player character is presumed to be able to see the same hidden ciphered messages that the player can, but where there is no means to solve the puzzle in the game interface and in such a way that the player character can be made to indicate having solved the puzzle of the coded message. It is a puzzle that is clearly located in the fictional world, but the solution is inaccessible in it and in the game’s interface more broadly.

Case study 1: “The Truth” segments in Assassin’s Creed II

The Assassin’s Creed series takes a particular approach to diegetic level in its storytelling. The story of each game is told on two different diegetic levels, in relation to two protagonist-characters. In the Assassin’s Creed II (Ubisoft 2009), the player is cast into the role of modern-age protagonist Desmond Miles, who re-lives the memories of his Assassin ancestor, Ezio Auditore da Firenze, through the use of the high-tech Animus device. Most of the time, the player controls Ezio, punctuated by brief periods of controlling Desmond between missions. Occasionally, players are reminded about the simultaneous operation of these two diegetic levels, as occurs when one of Desmond’s companions, who supervise his experiences in the Animus device, will chime in to describe or contextualise an object, place, or person of importance.

While it is not a puzzle game, Assassin’s Creed II features puzzle elements. Most of these puzzles are spatial. Like Ubisoft’s previous Prince of Persia releases (2003, 2004, 2005), there are puzzles around platforming, in which the player must, for example, navigate protagonist Ezio Auditore da Firenze to the top of the interior of the church of Santa Maria Novella using a network of scaffolding, rafters, chandeliers, and other environmental features. In a similar vein, there are puzzles that involve navigating Ezio from one location to another without being detected. These are typical diegetic puzzles in the sense that all the work done to solve them takes place within the game and its fictional world, and their rewards are also diegetic in the form of progression or story development.

Some of Assassin’s Creed II’s optional puzzles, however, are atypical in the sense that they demand that the player works non-diegetically in order to solve them. A set of optional puzzle sequences are activated by the player, controlling Ezio, finding and examining each of twenty hidden glyphs on the exterior of buildings. Finding these glyphs trigger puzzles hidden in the Animus device, which are accessible to Desmond, but not Ezio. The types of puzzles within these sequences vary from locating a hotspot in an image, to solving code wheels, to identifying which five of ten paintings have something thematic in common. On some of the screens where these puzzles take place, typically in the image hotspot puzzles, ciphered messages are hidden, and revealed if the player moves the cursor over them, with a key to the cipher likewise hidden elsewhere in the image. Desmond’s non-player character companions, who give hints to the immediate puzzle of finding the hotspots, do not mention anything about the ciphers, nor is there anywhere within the game interface to solve them. The player is left to decipher the coded messages outside of the fictional world. The content of the ciphered messages relates to the overarching historical narrative of the series, filling in gaps between the periods that the series-to-date covered (the Third Crusade, Renaissance Italy circa the Pazzi conspiracy, and the present day). The cipher puzzles are metadiegetic.

These ciphers act as a reward for paying attention and enrich the game play experience by giving the players a greater understanding of the game’s narrative and its world, as well as a sense of satisfaction from deciphering the messages, some of which can take significant amounts of work or research to decode if the player is not already familiar with the type of cipher used. While many of the ciphers are simple transposition ciphers, others such as the Masonic (pigpen) cipher, have a much less intuitive key by which to decode them and might require frequency analysis, brute force methods, or research in order to be able to decipher the message without prior knowledge of how the cipher works.

One such cipher puzzle (illustrated through the following images) involves a basic transposition cipher hidden in an image of Nicola Tesla at the Telefunken Wireless Station. The main puzzle solution involves moving the cursor over Tesla’s lap, which reveals that Tesla was in possession of one of the Pieces of Eden, a techno-magical artefact that the game’s protagonist Assassins and antagonist Templars are searching for.

The subsequent puzzle sequence strongly implies that Mark Twain was the Templar agent who stole the Piece of Eden from Tesla before handing it off to Thomas Edison, who is also a Templar in the game’s narrative.

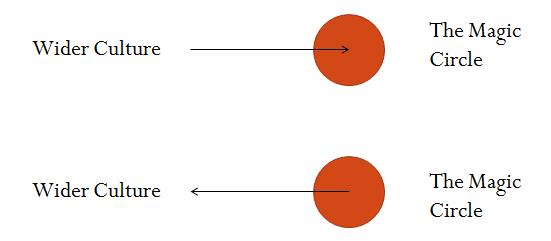

In addition to rewarding players with a deeper understanding of the game’s narrative, solving the ciphers offers additional possible rewards. The Tesla puzzle provides imaginative prompts for fan practice such as fan-fiction writing, as well as widening the game’s network of intertextual references. This is important because of a feedback loop that Katie Salen and Eric Zimmermann (2003) identify in games. Salen and Zimmermann argue that games are open cultural artefacts, in the sense that player-made cultural productions feed into players’ understanding of the game world, or the game world itself, and contextualise the game within the wider culture. The game and the wider culture continuously influence each other (Salen & Zimmermann 2003: 552). This argument employs Johan Huizinga’s notion of play taking place within a “magic circle” (Huizinga 1955: 57), a separate space in which the rules and pretences of the game are treated as real and centrally important (Huizinga 1955: 8).

The code-breaking game play sequence also explicitly destroys any sense of immersion in the game. If and when the ciphered message and key are discovered, the game effectively tells the player to leave and decode the cipher before coming back to solve the hotspot puzzle, which would involve moving the cursor such that the cipher would no longer be visible. At the same time, the code-breaking sequence fosters a sense of engrossment by signalling to the player to exit the game-world frame (to enter the game frame) with the specific promise of the player later returning to a more developed game-world. In other words, the game play sequence creates an integral aesthetic experience. Another way to conceptualise this change is through McMahan’s notion of extradiegetic engagement, in which the player shifts from being immersed in the game world to being involved in an external activity that is related to the game (code-breaking), though McMahan’s dual notions of immersion and engagement are not mutually exclusive with the engrossment framework.

The combination of out-of-game (extradiegetic) work and in-game (diegetic) reward involves some players in a more meaningful way than the typical combination of diegetic work/diegetic reward. Simultaneously, it does not alienate those players who never notice the hidden messages to begin with. This kind of player engagement through puzzles, though not limited to coded messages, is a device that game developers can and should use more often in order to engage players and provide richer experiences. This structure of involvement also accomplishes the same goal as its inverse, the gamification structure; greater levels of involvement from the player, with the main difference being that the involvement is in the puzzle/game as an aesthetic object rather than in an external, material, reward. This gameplay sequence does what gamification does while simply being a game.

Case study 2: simulating protein folding with Foldit

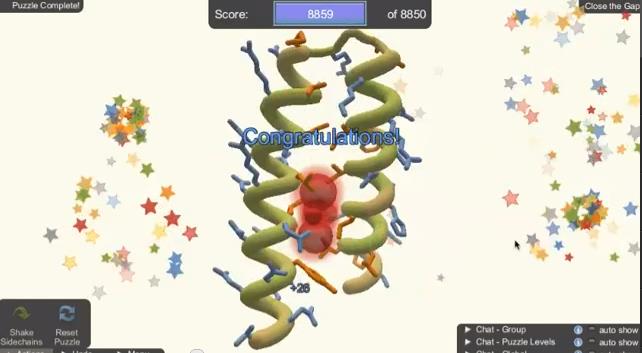

Where Assassin’s Creed II provides a clear-cut example of an extradiegetic work-diegetic reward structure in a gameplay sequence, the University of Washington’s Foldit (2008) provides a more complicated example of the interplay between work and reward, in game and out. Foldit is a game about folding protein, in which players are presented with protein strands and asked to use the game’s simplified protein folding tools to fold the protein into an optimal configuration. This involves manipulating simplified representations of protein strands such that the new shapes of the protein structure exhibit certain properties that physical protein strands would also have to have. For example, folding proteins in Foldit involves minimising empty space along the protein chain while also keeping sufficient distance between atoms, maximising the strength and efficiency of electrical bonds in the protein chain, and other criteria. The player has access to a number of computer-assisted tools to fine-tune the optimisation from a starting point that is determined by the player’s physical manipulation of the protein structure with the point-and-click interface. The idea behind Foldit is to tap players’ pattern recognition and problem-solving skills to help direct and speed up the computational side of protein modelling (UWFoldit 2012: 1:26-2:06). This has been successful in certain narrow but significant applications, leading to breakthroughs in protein modelling for certain protein structures and to new possibilities for protein-tailored antiretroviral drugs as treatment for HIV/AIDS (Khatib et. al. 2012).

Foldit is a game without a fictional world, so it would be odd to think about the work and rewards that a player undertakes and receives in terms of diegesis and extradiegesis. In that sense, its game play, while composed of a series of puzzles, are not fiction puzzles. At the same time, the work and reward structure in Foldit seems to operate on multiple levels. The player works ‘diegetically’ in the sense of within the game-frame, to optimise the shape of given protein structures, and receives rewards in that same frame, such as points and global leader-board rankings, as well as “fun animations and sounds” (UWFoldit 2012: 1:15-1:20).

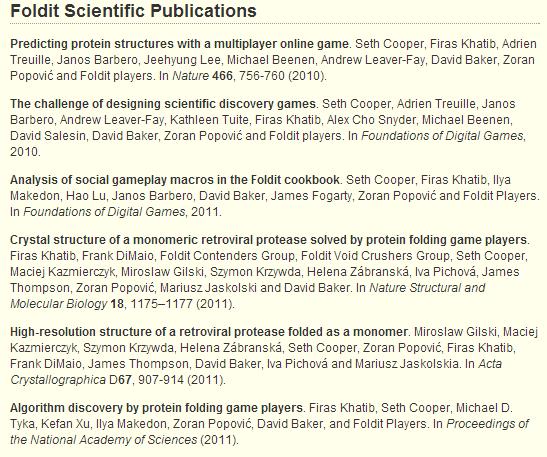

At the same time, the player’s work is translated into an extradiegetic context, in which it is used to assist medical research in the social frame of everyday life. This also leads to a further set of extradiegetic rewards for players, such as the satisfaction of contributing to medical research, and the social capital and recognition that comes with making these contributions through, for example, joint authorship credit on scientific articles describing Foldit-generated advancements (UWFoldit 2012).

Foldit incorporates diegetic and non-diegetic work and reward at different times. The developers of Foldit as well as external commentators rightly describe the game as making use of a gamified structure. As described in the above analysis, the work of players in the game combines with external rewards and creates a feedback loop that motivates the players in their play. Foldit also uses a similar meta-diegetic approach to Assassin’s Creed II’s code-breaking segments in that there are in-game rewards for contributing to solving out-of-game problems (that are simulated in the game).

As Foldit seems to cover the entire spectrum of diegetic and non-diegetic work and reward at different times, assessing the player experience is more complicated and is temporally contingent on which gameplay structure is operating at the given time. It can be argued that over the course of a long period of play, Foldit eschews immersion and favours an engrossment-based model of player-involvement. Players move between the social and game frames through the work they put into the game and the rewards they get out of participating.

Foldit ’s approach to gamification in particular enables particular forms of criticism. One can examine the game’s work/reward structure and make judgments about its ethics and efficacy. By engaging with diegetic and extradiegetic work and reward, Foldit treats each of its puzzles in a balanced fashion; each puzzle is presented as a matter of scientific and social importance, a self-contained challenge/aesthetic experience (Dewey 1934, Danesi 2002, Karhulahti 2012), and a gamified path to reward, which can motivate different kinds of players, in different ways, at different points in their play. In addition to the possibility of being more efficacious than a more ‘pure’ reward-based gamification, this use of gamification in concert with genuine, aesthetic, puzzle-solving experiences is also less exploitative. Foldit is a game, is gamification, and is possibly something else.

Tracking player involvement across a work/reward spectrum: a method for holistic criticism and analysis

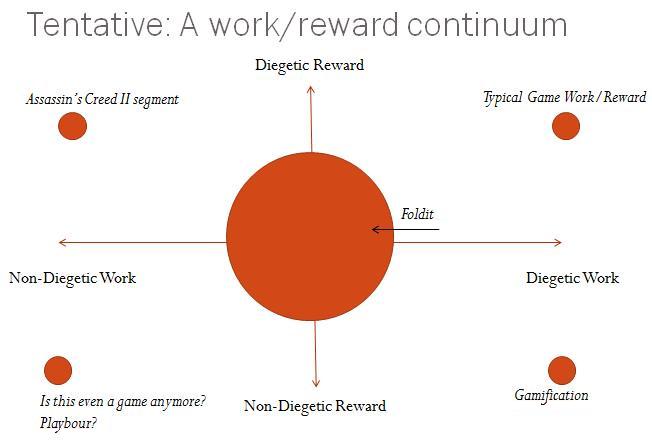

Extrapolating from discussing the case studies to discussing game studies and analysis in general, two possibilities stand out as potentially useful: first, the notion of a continuum of diegetic/extradiegetic work and reward, and secondly, that the player’s motivation and experience changes in response to shifts on that spectrum at certain points in time.

This work/reward continuum, tentatively, looks like this, in relation to the examples given in this article:

As discussed earlier, the typical game play structure of diegetic work and reward is at the upper right of the diagram. It is associated with play and reward within the game-world frame, when applicable in games with a fictional world and narrative, or the game-frame in games without those. At the lower right, a switch to non-diegetic reward changes the work/reward structure to that of gamification. The work is still put into the game-world or game-frame, but the motivating reward comes from and relates to the social frame. Games that award achievements and trophies also fit this structure of work and reward. Work is expended to play the game in the particular style that will unlock the given achievement/trophy, for the cultural capital that the achievement and trophy gives as a marker of status and skill. Mikael Jakobsson’s study of the Xbox Live achievement system as a massively multi-player online role-playing game (2011: online) provides a strong indication of this:

In contrast to the optional characteristic of achievements as scaffolding, this experience showed a glimpse into the force of the system leading gamers to engage with games in ways that they never thought they would. I did not realize it at the time, but I had ceased playing the trivia game and was at this point only playing the XLMMO [Xbox Live Massively Multi-Player Online Game]. (Jakobsson 2011; emphasis in original)

At the upper left, the work/reward structure shifts again, to non-diegetic work yielding diegetic reward. This is the game play structure of the Assassin’s Creed II code-breaking puzzle game play segment. At the lower left, non-diegetic work and non-diegetic reward suggests that players are doing something other than playing a game when this game play structure is in effect. One suggestion for what occurs in this situation is playbour, exploitative work disguised as play, the extreme negative kind of gamification, particularly if players are being misled to think that they are simply playing a game.

Assassin’s Creed II ’s code-breaking puzzle segment, in the context of the entire game, its narrative, and its setting, is a tiny part of the overall Assassin’s Creed II experience. It is an optional puzzle that takes place within an optional puzzle, with no resemblance to the third-person action game play that characterises the Assassin’s Creed series. A player can easily engage in hours of typical game play before coming across this kind of puzzle, and the player is quickly returned to typical game play after solving it. Encountering this puzzle entails a fairly extreme pair of shifts in game play experience that occur within a very short time; the type of work shifts from diegetic to extra-diegetic, and then back. I have argued that what happens to the player in the code-breaking gameplay interval is that this shift in gameplay focus provides a richer, more motivating game play experience for some players, though it might also alienate others, or fail to engage them as intended. For example, players may be driven to consult an online walkthrough rather than to crack the code themselves.

Players respond to shifts in how the game play experience is structured in terms of work and reward over time. Examining how players respond to these shifts can lead to more developed and nuanced accounts of players’ game play experiences and the efficacy of game mechanics. This is the case whether researchers analyse individual experiences by way of deep reading (Keogh 2012), analyse collective experiences in aggregate statistically (Ermi & Maÿra 2005), or engage in micro-sociological analyses and extrapolate from the data gained (Deterding 2013).

The case of Foldit further demonstrates the importance of a temporal approach to the game play experience, as every possible configuration of work and reward can be present at different points in time. Examining game play in terms of shifts in work and reward structures over time is central to examining the player experience as well as the efficacy of the game’s design in such a case. Frame analysis is a viable method for conducting this analysis as these shifts in activity are accompanied by shifts in frame. These kinds of analysis can be used in order to address questions such as whether diegetic or non-diegetic rewards motivate players more at certain points in play, or how players perceive the kinds of work they put into the game play activity.

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that an engrossment-based framework best allows us to understand shifts in player involvement in games over time, especially when the work expected of the player and the rewards received by the player are variably diegetic or extradiegetic. I have also proposed a continuum of work and reward in games that can allow us to track shifts in the work/reward structure of games over time, allowing us to focus our attention on the temporal aspects of these shifts and the game play experience. We can identify gameplay sequences where the typical structure of diegetic work leading to diegetic reward is temporarily replaced, and analyse them in relation to the whole of the game in order to examine the possible intended effects of these shifts, what degree of aesthetic efficacy they have.

The initial analysis of the case studies presented in this article points to several conclusions that might be generally useful springboards for temporally-based, frame-analytic accounts of atypical gameplay sequences (per Deterding 2013). First, the assumption that gameplay should be structured around diegetic work leading to diegetic reward is not necessarily true. Changing this structure through strategic and aesthetic design decisions can lead to interesting, generative, and engaging aesthetic experiences that are desirable.

Second, while positioned as a work/reward structure that involves players deeply in a game, gamification is not necessarily any better of a design strategy in general than its opposite structure, which is found in the hidden cipher puzzles in Assassin’s Creed II. While gamification sometimes fosters a player’s deep involvement in gameplay, it is sometimes antithetical to that outcome. For example, adopting a play-style optimised for attaining achievements or external rewards can be potentially jarring and deleterious to a sense of immersion, engrossment, or involvement in a game. The hidden cipher gameplay sequence from Assassin’s Creed II is highly engaging for those players that embark upon solving the optional puzzle while requiring effort outside the game and keeping the rewards strictly inside it.

Third, a new field of possibilities opens up when games blend diegetic and non-diegetic work and reward, as the example of Foldit demonstrates. Foldit resists classification and demands close temporal analysis because the game play experience fluctuates in response to the flow of gameplay and the player’s individual motivations over time. The micro-sociological surveys of gameplay that Deterding (2013) advocates for are a useful approach to this, though a great amount of detail is required to account for shifts in player attitudes coinciding with shifts in gameplay structure.

Fourth, and finally, game studies can benefit from a more refined vocabulary to deal with work and reward in games, especially as it relates to the player experience. This paper has provided a tentative one with the work/reward continuum, as well as its use of Fine’s engrossment framework and Karhulahti’s puzzle aesthetics. There are also a number of possibilities for further research in this area. Interdisciplinary research with scholars in fields such as sociology and psychology might yield further insights into the ways that work and reward operate in games. The design of work/reward systems for games for social change and gamified systems might be further examined and improved in light of these conclusions.

Works Cited

Aarseth, E. (1997) Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Althusser, L. (2008) On Ideology, London & New York: Verso.

Calleja, G. (2011) In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation, Boston: MIT Press

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York: Harper Perennial.

Danesi, M. (2002) Puzzle Instinct: The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Deen, P.D. (2011) “Interactivity, Inhabitation, and Pragmatist Aesthetics” in Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research 11: 2 http://gamestudies.org/1102/articles/deen

Deterding, S. (2013) “Modes of Play: A Frame Analytic Account of Video Gaming”, presented to Graduate School of Media and Communication, Hamburg University, Hamburg, 14 August.

Dewey, J. (1934) Art as Experience. From The Collected Works of John Dewey, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University

Ermi, L. & Maÿra, F. (2005) “Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion”, presented to DiGRA Conference 2005 - Changing Views: Worlds in Play, 16-20 June, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Fernández-Vara, C. (2009) “The Tribulations of Adventure Games: Integrating Story into Simulation through Performance” (PhD Thesis), Atlanta: Georgia Institute of Technology.

Fine, G.A. (1983) Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Galloway, A. (2006) Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

GeopLP (2012) “Assassin’s Creed 2 - The Truth (Part 3)”, viewed, 14 June 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IXR2U1llwk8

Goffman, E. (1974) Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Boston: Harper Colophon.

Grau, O. (2003) Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Huizinga, J. (1955) Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, Boston: Beacon Press.

Jakobsson, M. (2011) “The Achievement Machine: Understanding Xbox 360 Achievements in Gaming Practices” in Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research 11: 1 http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/jakobsson

Karhulahti, V-M. (2012) “Adventure as Art: The Aesthetic Value of Puzzles”, Proceedings of the 6th Philosophy and Computer Games Conference, January 29-31, Madrid, Spain.

Keogh, B. (2012) Killing is Harmless: A Critical Reading of ‘Spec Ops: The Line’. Online: Stolen Projects.

Khatib, F., et. al. (2012) “Crystal Structure of a Monomericretroviral Protease Solved by Protein Folding Game Players”, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 18 pp. 1175-1177.

Mackay, D. (2001) The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: A New Performing Art, Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

McMahan, A. (2003) “Immersion, Engagement, and Presence: A Method For Analysing 3-D Video Games” in The Video Game Theory Reader (Wolf & Perron, eds), New York: Routledge. pp.67-86.

Montfort, N., & Bogost, I. (2009) Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Murray, J.H. (1997) Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, New York: Free Press.

Prince, G. (1987) A Dictionary of Narratology, London: University of Nebraska Press.

Rey, P.J. (2012) “Gamification, Playbor, and Exploitation”, viewed 14 June 2013, http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/10/15/gamification-playbor-exploitation-2/

Ruggill, J.E., & McAllister, K.S. (2011) “Aimlessness” in Gaming Matters: Art, Science, Magic and the Computer Game Medium, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 32-49

Salen, K. & Zimmermann, E. (2003) Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Cambridge: MIT Press

UWFoldit. (2012) “An Introduction to Foldit”, viewed 14 June 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvYFjo3vCk

Zichermann, G. (2011) “How Games Make Kids Smarter”, presented to TEDxKids Brussels, Waterloo, Belgium, 1 June. http://www.ted.com/talks/gabe_zichermann_how_games_make_kids_smarter.html

Biographical Note

Michael Ryan Skolnik is a doctoral candidate at Swinburne University of Technology, researching interventionist aesthetics and videogames. He is a media/performance artist whose work has involved augmented reality and hybrid live/game spaces. His most recent performance, Occupations: A Forum (2013), examined urban protests and police responses using Augusto Boal’s aesthetics of Theatre of the Oppressed and a play-space generated in Jason Rohrer’s independent videogame Sleep is Death (2010).