Direct-On-Found Footage Filmmaking: Mining the debris of image consumption & co-directing with nature

Katherine Berger

It is undeniable that images and the screen dominate much of our waking lives, pilfering our eyes as we privilege the visual. However, as the digital gains ubiquity, it’s the experimental film artist who mines the debris of our image consumption gluttony. There is a small but rising contingent of contemporary film artists who utilise and rescue analogue technology from its demise, namely the latent archive of pre-existing footage, and rework the images via handmade, direct-on-film animation techniques. I am a player in this resurgence, choosing to rehabilitate past images and favour the physical object of film. Although, I take advantage of digital technology (when it comes the capturing, editing and dissemination of my films), as a complete contrast to creating images digitally, a method of utilising analogue film in combination with the natural world and it’s elements is employed. This contemporary junction is of interest; where the proliferation of digital offers a ‘freedom’ and ease for modern filmmaking, yet the lingering potentials of analogue and the ‘hands-on’ becomes increasingly pertinent as we move swiftly through the digital era.

Firstly, it’s interesting to note that the practices of using pre-existing footage (commonly referred to as ‘found footage’) and ‘ direct-on-film animation’, both which have prevailed since early cinema, have usually been documented as separate practices. Seldom has this intersection of both practices been examined, and although historical examples of direct-on-film animation were predominantly created on clear leader or opaque (processed) film - examples as far back as the 1930’s (discussed later in this article) can be uncovered where direct-on-film animation has been employed on pre-existing footage. So while many contemporary found footage filmmakers have embraced what digital technologies offer (such as already digitised vintage footage such as rare educational films) there are still an evident number of filmmakers (more so from the 1980’s to the present) who are still intent on exploiting film’s analogue properties and often laboriously animating vintage, pre-existing footage frame by frame. Due to this intersection of activity, the neologism ‘direct-on-found footage animation’ can be activated.

To create a direct-on-found footage animation, techniques such as scratching, scraping, gluing, cutting, burning, painting, drawing, treating with various chemicals or burying the film in the earth to hasten the decaying effects are employed on the surface of found footage. These materialist investigations were particularly prevalent in the 1960’s and 1970’s (when there were strong avant garde movements taking place, particularly in North America, the UK and also pockets of activity in Australia). However, while these hands-on techniques were used to reaffirm the physical presence of the artist through the direct relationship with the filmstrip, the artists (during this period) were more often more concerned with abstraction and foregrounding the material of film to break the illusory function of mainstream/ Hollywood cinema. What shouldn’t be disregarded is when the use of found footage, in conjunction with direct animation, is the significance of disrupting the physical surface of the film, in addition to disrupting the original pre-existing images that lay embedded within the substrates of the emulsion. As William Wees, a highly regarded proponent of using recycled images, succinctly stated,

When a film's starting point is neutral, imageless leader, the emphasis falls entirely on the dance of lines, shapes, textures and colours created “out of nothing” by the filmmaker. When the filmmaker works on found footage, something different happens. In addition to their innate interest as gestures of personal expression, the visual effects added by the filmmaker assert the individual filmmaker’s power to reclaim the terrain of public images for personal use. Thus even the most painterly and abstract found footage films offer an implicit critique of the film industry’s standardised representations of the world, and like other kind of found footage films, they interrupt the endless circulation and unreflective reception of mass media. (Wees 1993:32)

As Wees posits, “something different happens”, it’s almost like the filmmaker becomes that of an alchemist who turns lead into gold, taking part in an almost mystical and metaphysical event that gives the filmmaker the “power to reclaim the terrain of public images” (1993: 32).

Thus, the direct film artist can create works that move beyond abstraction to become works that invert and/or subvert the pre-existing images and offer various commentaries concerning our image-consuming lives. Furthermore, as analogue film succumbs to decay and degradation over time, just like the human body or the natural world, the film artist can draw a comparison between the fragile body of the film, the fragile body of the filmmaker and the fragile body of the world around us. Contemporary experimental film artists who employ hand-manipulation methods would argue that questions regarding life, and ultimately death, can be prosed through the medium of celluloid film, including what is life without touch, without physicality? What is life without decay? What has the medium of film left to tell us? How is the object of ‘found footage’ and the potential to inscribe on it via direct animation techniques still relevant in today’s digital era? Just like psychics propose to be a medium between the living and the dead or the present and future, the medium of film acts as a platform for communication for the film artist.

The significance of using actual found footage lies in the fact that it is an artisanal mode that can only take place in the real, physical world; no type of digital machinery can copy this process. The film artist needs the tangible film to sustain a corporeal relationship with the film medium. It also ensure that the film artist was indeed dealing with ‘found’ footage, as in the digital realm people were making films out of reused material that was not really ‘found’ anymore, but perhaps ‘ripped’ off a DVD or taken from archives already digitised online. It’s the use of the actual object of film where the film artist can arguably ‘communicate’ through the medium of film and as the wild concept mentioned earlier, ‘communicate’ with the natural world by allowing nature to take part in the affecting and animating of the filmstrip. By relying on chance and randomness to play a part in how the film is degraded and decayed, the film artist takes advantage of a tactile and hands-on relationship with the film surface and uses the natural world as a ‘co-directing’ force to create films. A film theorist who has written extensively on direct-animation and the North American avant garde, Tess Takahashi, proposed for her paper, After the Death of Film: Writing the Natural World in the Digital Age, that “the ways in which celluloid film’s capacity for registering the marks made by the artist’s hand, natural elements and accidents function as writing” (2008). Therefore, suggesting a new language or a form of communication, where the natural world can take part, can be created via direct-on-found footage animation.

By using the archive to create new works, film artists are also commenting on the photographed image as ‘historical truth’ and reclaiming images that were once used to shape our society, morality and worldviews. Furthermore, forming a dialogue with history and with the present world and creating new narratives and new histories or historiographies.

The borrowing and reanimation of the archival fragment becomes as way of disturbing the smooth structure of an historical narrative, in order to reintroduce the possibility of other realities in the gaps and pauses” (Cocker 2009).

With the advancements of digital technology over the last few decades, a concomitant result, not only is an increase of pre-existing found film to be re-investigated and re-inscribed (rather than discarding or simply consigning it to various archives), but digital’s ability to capture these films that are constantly in a state of decay and flux. This allows the film artist to still have a corporeal relationship with the film medium, which the viewer is aware of, whilst capturing the delicate decay and degradation of the film image (whether natural or created on purpose by the artist through the various hand-manipulation methods). Furthermore, as each film has a life span, just like human beings, we can look after it as much as possible but eventually the memento mori and relentless melt (a term coined by Sontag 1997:15) of the emulsion remains - it cannot last forever.

Just like the cell dividing and multiplying nature of humans, no two film-cells are exactly alike. Each cell of each film is unique. Scratches and marks on a film are akin to the wrinkles and scars on a human body or the rings on a tree trunk, the emulsion of film is like a layer of skin that holds and protects the image and the history and memories contained within. They demonstrate time, reaffirming that we are all organic matter and bear the condition of decomposition, which is a natural, inevitable occurrence. Analogue film has a tactile quality that in a sense “breathes and wobbles” (Bertrand and Routt, 2007:97) as it constantly shifts in time and decays. Therefore, in an era of digital proliferation of images, the emphasising of the analogue, the handmade and the photochemical are key strategies for film artists to create thought-provoking works. Film artists are able to, in a sense, bring unknown distant places and/or fascinating characters into their own world and allows them to see not just old film but endless possibilities, as the images contained within each reel or tin could be given a new life and created into a new film. As Susan Sontag states, “To collect photographs is to collect the World” (Sontag 1977: 3). The film artist can go beyond the visual, the 2D nature of the images and in an almost metaphysical sense; go beyond the immediate surface of the film and drive deeper into its ‘layers’. By hand-manipulating film, the film artist can inject their ‘self’ into a film’s ‘history’ and create a new trajectory for the chosen footage via the touch of the filmstrip.

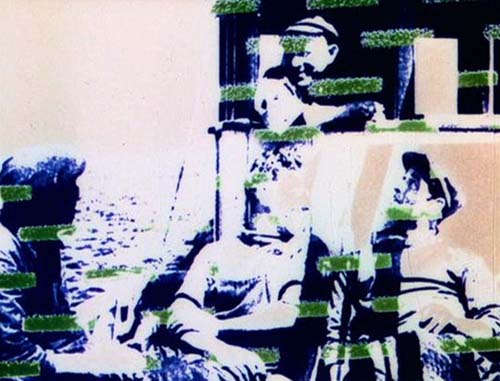

To look back at the history of Direct-on-Found Footage Animations and uncover key examples, Len Lye, a pioneer of direct-on-film animation, actually made one of the very first Direct-on-Found Footage Animations in 1937 called, Trade Tattoo. Whilst working for the UK General Post Office Film Unit, Lye created the film by using found outtakes from other GPO Film Unit documentaries, such as Night Mail (1936). Lye transformed the original black and white footage of dull postal duties, into a vibrant, colourful display – hyping up the life of a postal worker to seem so much more interesting. Lye wanted to evoke a “romanticism about the work of the everyday” (Horrocks 2001:151) and did so by adding colourful markings directly onto the film stock, in tune with upbeat music. Although one of the first examples of Direct-on-Found Footage Animation, it’s rarely acclaimed for its use of found footage and it’s subversion of the original images; Lye’s direct-on-film animation techniques have only really been of interest to date.

Another early example, prior to the explosion of video and digital technologies was a film by Hy Hirsh called, Scratch Pad from 1960. It was created on 16mm found footage and went for approximately 7 minutes. Hirsh scraped and scratched over footage of streets and urban areas, abstracting the images and drawing attention to the graphic lines found in urban areas, such as the roads and telegraph poles. Hirsh’s film, ultimately commenting on industrialisation and the new manufactured landscape, which was taking over the natural environment.

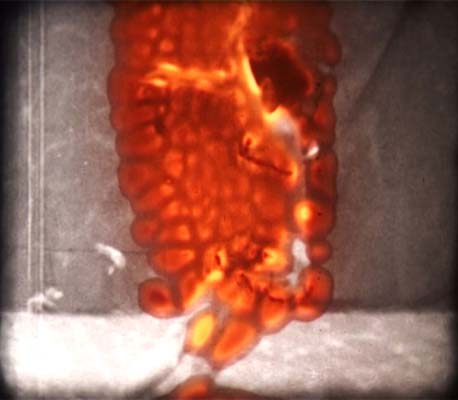

The late 1970’s to early 1980’s saw an obvious increase in Direct-on-Found Footage Animation since the advent of digital, which had began its rise to become the new filmmaking and exhibition format. As a result, motion film went through a period of futility and was often discarded or destroyed, particularly amongst the big studios that were excited by the prospect of digital. A key example from the 1980’s is by the German Schmelzdahin Collective with their Direct-on-Found Footage Animation, Stadt in Flammen (1984, 5 minutes, Super 8mm). The group from Bonn in Germany saw themselves as film alchemists and wanted to push the selected footage (mostly found and sometimes photographed) into a ‘metamorphosis of earthly digression’. They worked, in a sense, in harmony with Nature as they often left their films up to elements of chance and allowed the natural environment to make its mark upon the pre-existing images that lay on the filmstrip. To create Stadt in Flammen, the found footage of a film with the same title (created only a few years prior), was subjected to various substances and buried in the earth or left in a pond for several months to hasten the decay of the film’s original images. Author Owen O’Toole writes, “Stadt in Flammen is the most volcanic film I've ever seen; the emulsion literally crawls off the film base, like a lava flowing across terrain… Like ancient paintings crack and fall away from their surfaces” (O' Toole 1989/90). This film is significant because of its collaboration and co-direction with the natural world in the production of the film.

From the year 2000 onwards, we can find a number of examples of film artists directly animating on found footage (new distribution methods and a wider dissemination of films across digital networks can account for this). An example from 2000, is Brian Frye’s Oona’s Veil (8 mins, 16mm), where Frye took a screen test of Charlie Chaplin’s wife Oona, her only film-record, and “reconstructed the footage into an intense meditation on seeing and being seen” (Diagonal Thoughts 2008). Furthermore, the original footage was “mutilated, exposed to chemicals and even buried. The result is an unearthly film portrait, with occasional spots of black emulsion, creating a continuously shifting exchange of glances between the image and the spectator” (Diagonal Thoughts, 2008).

Another example from this period is a film called, DECASIA: The State of Decay (2002, 70 mins, 35mm), by American film artist, Bill Morrison. Morrison has made a number of films where the decay of pre-existing footage is revealed with enormous flair. In regards to his film Decasia, Morrison went to various film archives and asked if he could use any decaying and decomposing films, particularly footage from the conception of motion pictures. As a result, Morrison digitised highly flammable and severely decayed nitrate-based films from 1910-1918. The footage that Morrison selected were of images that bubbled, twisted, and morphed on the filmstrip, otherworldly images that came to life through the movement of the decay. Whereas highly preserved vintage film or photographs seem to slice a moment and preserve time, in this instance the decay of the images don’t let us forget time’s ‘relentless melt’ via Sontag. Although it is the natural decaying function of film that is a primary point of fascination, it is concurrently the importance of digital technologies, which is equally significant, as it is through the digital that the decay was captured.

Another contemporary example is by Australian Filmmaker, Tony Lawrence and his film, Girl on Fire (2008, 2 mins, Super 8mm). Lawrence purchased vintage footage online of a girl who was filmed underwater, seductively swimming on the bottom of a pool. However, due to the poor conditions of storing the film (where the film repeatedly got wet over the years), it resulted in the film suffering fiery, amber rusty spots. However, what is so remarkable is that it’s almost as if ‘nature’ chose to only affect only the girl with rust and as a result, she appears as if ‘on fire’. Her youthful beauty that she may have wished to be immortalised and seen by many on film, could not escape the impending ire of nature and time.

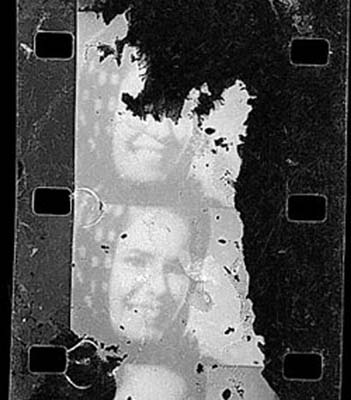

A significant artist who has made a number of films directly animating on the surface of celluloid film and incorporating the natural elements into her creations, is the Canadian film artist, Louise Bourque. Bourque utilises hand-manipulation techniques to create her films, which focus on abstraction, colour, texture and promotes what Bourque sees as, “disintegration as transformation” (2004). Jours en fleurs (35 mm, 4.5 minutes, 2003) was the title of Bourque’s film, which referred to a woman’s menstrual cycle, translating roughly as Days in Bloom. Bourque took pre-existing footage of trees and flowers and soaked the strips of film in menstrual blood for several months to create the film of sparkling and translucent patterns and vibrant colours. The film has a distinct feminist edge and as Bourque states, “The film captures both the beauty of nature and its destructive force… I think of the film as a collaboration with nature” (2004). Another interesting example of Bourque working with nature and the corporeality of both her film practice and her own body is the film, Self Portrait Post Mortem (35mm, 3 minutes, 2002). Not strictly, found footage, but footage that Bourque had buried and forgotten about 5 years prior of herself that were apparently, “captured by chance” (Malone 2006). During the production of one of her early films. Bourque referred to the film as “an exquisite corpse” and that she was once again employing, “nature as collaborator" (Malone 2006). In the film, the luminous images are being taken over by the decay, which nature presents as a way to inscribe on and transform the footage and create an “unearthed time capsule, containing long-buried footage of the maker's youthful self” (2006). The footage becomes rumination on the nature of time, decay and our inevitable aging, which is aligned with the natural world that one day our bodies will return to the earth.

Try that we might to control it; nature is a force that we, as the human race, must surrender to. When discussing the natural world as a co-director of direct-on-found footage films, an interesting case study is the salvaged films of film artist Helen Hill after Hurricane Katrina. We can argue that nature participated in the creation of new works between nature and Hill. Hill had shoot numerous rolls of film prior to the Hurricane around the streets of New Orleans where children could be seen playing and people going about their day. Yet after being submerged in the water for over two weeks, the film was now being taken over by a powerful display of decay threatening to swallow up each frame until there was nothing left. Rather than dispose of the films, Helen Hill discovered nature had left its mark on her original footage and it was a call to create new films. Furthermore, Hill discovered she had a way of representing the ‘unrepresentable’, which was the force of the Hurricane. Unless you lived through it, it’s hard to visualise the ferocity something of this magnitude can cause except the standard aftermath imagery. Hill’s films demonstrate something indescribable and undefinable through the wrathfully decayed images left in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. As the natural world has played silent witness to everything the human race has done from the dawn of time, what better way to reinscribe and reimagine the historical artefacts of pre-existing footage than have nature and the natural world take part in it?

A noteworthy example about the powerful poetics of decay is in relation to the film The Story of the Kelly Gang from 1906 directed by Charles Tait. The National Film and Sound Archive invested a lot of money salvaging what footage remained from (what is referred to as) the first feature film ever made. However, if we look beyond the sections that are seemingly unaffected by age, what stands out are the parts where the “movement seems ‘organic’ and animated, bubbling or pulsing, breathing; arguably more alive than any represented life, closer then to cinema-life” (Bertrand and Routt, 2007: 97-98). The authors of the book accompanying the DVD release goes on to say, “the movement of decomposition appears undirected, motivated but uncontrolled, confined but infinite in its permutations – a manifestation of Eisenstein’s three- of four-dimensional cellular montage.” (Bertrand and Routt, 2007: 97-98). However, rather than saying it appears ‘undirected’, we could argue that nature and the natural environment was assisting in the direction of the footage, making its mark on the footage along with time.

Direct-on-Found Footage Animation artists “embrace a process-oriented mode of production, in which the film's form and subject are discovered in the course of the making, rather than following a preconceived script or plan - an art of discovery, then, not only of management and execution” (Gehman 2003). It is not the final film but the process in which it was created that is the key aspect to this artform. To work in this way is a process of discovery, it’s akin to performance and relies on direct experience for the filmmaker. It also relies heavily on chance and the accidental. There have been many art movements and cultures that have placed high importance on the role of chance and allowing nature to take its natural course in art from the Chinese Taoists to Dada artists. The Dadaists felt that the work of art wasn’t and shouldn’t try and be in the artist’s control, and is a way they could go against what was perceived as logical. Dada artists also found it was a way to return to nature and the cosmological forces of the universe. The Dada artist, Hans Arp, believed that the following of laws of chance creates ‘pure life’ and ‘gives us access to mysteries’. This is similar to the Taoists who believe in chance, spontaneity and trusting one’s intuitive intelligence, which ultimately leads to what they referred to as “harmony with nature” (Capra 1991).

To delve a little into my own film practice, I consider the power and the poetic beauty of co-directing with Nature, and sense a reconnection and rekindling of a relationship to Nature through the organic material and physicality of film. An example is a film titled, Mother Tongue, created from 16mm film source material purchased online (when I was staying in the far north of Canada), The film was from the 1950’s and was the capturing of an Inuit family going about their day in the frozen Artic – most likely taken by an anthropologist. The footage, which originally belonged to the National Film Board of Canada, was a magical time capsule of a passing way of life due to climate change, industry and urbanisation. Although the footage was already impressive, I decided to take the film with me on a trip to Tasmania, and buried the film in some fairly dense rainforest. On the opposite ends of the world, industry and the greed of wealth was affecting both landscapes. The footage was uncovered again only two months later, and only very lightly cleaned so that I could run it through a flat-bed editor and capture the decaying images digitally. The footage that resulted from the almost ritualistic burying was a vibrant splashing of colours reanimated on the surface of the film. The images, which had become quite muted in tones over the years, were now bursting with colour and movement due to the emulsion decay and decomposition and the images would hide and reveal amongst the decay. By treating the filmstrip as a sort of writing surface, Nature can be seen as inscribing itself on the film and creating it’s own commentary on perhaps the natural world suffering at the hands of industrialisation. Furthermore, there are ethical implications of using found footage, particular of a native Inuit family, where questions are raised about the representation (and often exploitation) of indigenous culture. The work was created with the idea of co-directing with nature in mind and a desire to open up a dialogue for communication, reception and perception of the world around us through the medium of analogue film.

While digital technology threatens to make analogue film obsolete, this has not stopped the fervent examination of experimental filmmakers to seek pre-existing footage to use in conjunction with techniques of direct animation. Utilising a ‘hands-on’ approach to filmmaking, which has become particularly meaningful, as we become increasing separated and fragmented by living our lives through the screen. The significance of analogue film in the creation of Direct-on-Found Footage Animations, in a highly ubiquitous digital landscape, is its ability to operate as a tool for communication and become a meeting point for the film artist, the film as a body, and the world at large. The spectator can also be assured that the filmmaker had a corporeal relationship with the filmstrip – drawing attention to the physical world and the importance of our presence in it. This direct relationship with the film medium and its ability to transform, mutate and decay raises pertinent questions including our ephemerality and also our dependence on the image as memory or historical truth. Furthermore, while digital cinema is missing that alchemical trace, it has allowed for the capturing of various states of decay of the film image and allowed filmmakers to work with nature in ways that we may never have first imagined. In the creation of Direct-on-Found Footage Animations, no longer is the visual privileged over other senses, and what emerges is a much-needed reclamation and examination of our over-consumption of images.

References

Bertrand, I. and Routt, W.D. (2007) The Story of The Kelly Gang, Victoria: Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM)/The Moving Image.

Capra, F. (1991) “Taoism”, The Tao of Physics – The Way of Eastern Mysticism, http://www.uni-giessen.de/~gk1415/taoism.htm, accessed June 18, 2012.

Cocker, E. (2009) “Ethical Possession: Borrowing from the Archives”, in Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies, Nottingham Trent University, UK, http://www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/cultborr/chapter.php?id=9, accessed May 29, 2012

Diagonal Thoughts Website (2008), “Ghosting the Image / Program Notes” (June 4), http://www.diagonalthoughts.com/?p=140, accessed May 29, 2012.

Fan, L. (2004) “Louise Bourque, Beyond the Fringe”, Free Online Library, http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Beyond+the+fringe.-a0126683522, accessed June 10, 2012.

Gehman, C. (2003) “The Independent Imaging Retreat Website”, http://www.philiphoffman.ca/filmfarm/Chris_Gehman.htm, accessed June 10, 2012.

Horrocks, R. (2001) Len Lye: a Biography, Auckland: Auckland University Press

Malone, M.J. (2006) “A Conversation With Louise Bourque” (March 19), http://www.bigredandshiny.com/cgi-bin/mobile.cgi?section=article&issue=39&article=A_CONVERSATION_WITH_18212542 , accessed June 10, 2012.

O’Toole, Owen (1989/90) “Stadt in Flammen”, Arsenal Distribution Website, http://films.arsenal-berlin.de/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/9045 , accessed May 29, 2012.

Sontag, S. (1977) On Photography, New York/Ontario: Penguin.

Takahashi, T. (2008) “After the Death of Film: Writing the Natural World in the Digital Age”, Issue 42.1 (January), http://visiblelanguagejournal.com/web/abstracts/abstract/after_the_death_of_film_writing_the_natural_world_in_the_digital_age , accessed May 29, 2012.

Wees, W.C. (1993) Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films, New York: Anthology Film Archives.

Filmography

(In order discussed in article)

Trade Tattoo (Len Lye, 1937)

Night Mail (GPO Film Unit, 1936)

Scratch Pad (Hy Hirsh, 1960)

Stadt in Flammen (Schmelzdahin Collective, 1984)

Oona's Veil (Brian Frye, 2000)

DECASIA: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002)

Girl on Fire (Tony Lawrence, 2008)

Jours en fleurs (Louise Bourque, 2003)

Self Portrait Post Mortem (Louise Bourque, 2002)

The Story of the Kelly Gang (Charles Tait, 1906)

Mother Tongue (Katherine Berger, 2011)