Scan Magazine: 2007-11-01

Determined Indeterminacy A Review of THE THIRD MIND at Le Palais de Tokyo Curated by Ugo Rondinone

THE THIRD MIND

Le Palais de Tokyo

13, avenue du président Wilson 75116 Paris

September 7th – January 8th

Ugo Rondinone and the new director of Le Palais de Tokyo, Marc-Olivier Wahler, have mounted a high-quality group show that criss-crosses an assortment of generational frontiers and stylistic barriers. Ugo Rondinone is an artist known for his talent for building systems of connections and, given the visual results of this exhibit, he has, in large part, very good taste in art. I particularly enjoyed his assembling excellent works of Brion Gysin, William S. Burroughs, Ronald Bladen, Lee Bontecou, Andy Warhol, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland, Martin Boyce, Paul Thek and Emma Kunz.

I think what might be interesting about this disquieting show, is to look at how this group show differs in its conjoining (or not) from other group shows by pinning it to the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs from the early 1960s known as The Third Mind. Also we can place THE THIRD MIND in the context of wider connections and ponder at what point does homage turn into exploitation?

First some background. Beat writer Burroughs and the artist Brion Gysin, known predominantly for his rediscovery of the Dada master Tristan Tzara's cut-up technique and for co-inventing the flickering Dreamachine device, worked together in the early 1960s on a publishing project that used a chance based cut-up method. A cut-up method consists of cutting up and randomly reassembling various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning. 1+1=3

In the recent biography of Allen Ginsburg, Celebrate Myself, Ginsburg’s archivist, Bill Morgan, excellently recounts some of the genesis of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs forays into radical Dada cut-up technique and collaboration based on Ginsburg’s diary entries.

Gysin in the mid 1950’s pointed out to Burroughs that collage technique has been a regular tool in painting and graphics since half a century. This came as late news to the young Beat writers of that time, so it is perhaps not surprising that Ginsburg’s first exposure to Burroughs’s use of the cut-up was met with disdain – Ginsburg considered it something along the lines of a parlour trick. (p. 318) Even more, Ginsburg speculated from New York that Burroughs had lost his mind through lack of sex. As a joke, Ginsburg and Peter Orlovsky cut up some of their own poems and rearranged them and sent them to Burroughs with the note “Just having a little fun mother”. (pp. 318 – 319). However Burroughs was so dedicated to the random cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique. When Ginsburg and Orlovsky arrived in Tangiers in 1961, Burroughs was working on an even more advanced use of the cut-up; he and Ian Sommerville were cutting and splicing audiotapes and Burroughs was making collages from newspapers and photographs while proclaiming that poetry and words were dead. (pp. 331-332)

Burroughs however soon began work on a cut-up novel, the Soft Machine, drawing material from his The Word Hoard, a collection of Burroughs’s manuscripts written in Tangier, Paris, and London that created the super mother-load manuscript serving as the basis for much of Burroughs’s cut-up writings. This manuscript was soon being “assembled” and edited by Ian Sommerville and Michael Portman; Burroughs’s companions. Sommerville was regularly speaking of building electrical cut-up machines.

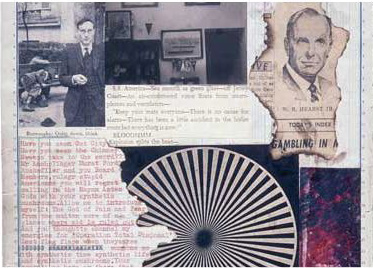

Fig. 1: William Burroughs & Brion Gysin, from The Third Mind

Burroughs would soon begin collaborating on a book project with Brion Gysin using the cut-up method; cutting up and reassembling various fragments of sentences and images to give them a new and unexpected meaning. The Third Mind is the title of the book they devised together following this method - and they were so overwhelmed by the results that they felt it had been composed by a third person; a third author (mind) made of a synthesis of their two personalities. Ginsburg remained highly skeptical for some time, but following his travels in India came to appreciate the cut-up technique, even while never employing it.

Now for THE THIRD MIND show itself. Two major works (themselves multitudinal) advance well Rondinone’s thesis of the third mind. Of course, foremost is the Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs collaboration The Third Mind. An entire gallery is devoted to the maquettes for this unpublished book from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art - and it does not disillusion the fourth mind: that of the viewer/reader. It is a golden hodgepodge feast and serves as the underpinnings of the exhibit.

Then there is the glamorous video installation/accumulation of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests from 1964-1966: a group of silent b&w three-minute films in which visitors to the Warhol factory try to sit still. Here we see an interlaced presentation that visually connects the youthful faces of Edi Sedgwick, Susan Sontag, Nico, John Giorno, Jonas Mekas, Gerald Melanga, Jack Smith, Paul Thek, Lou Reed and the distinguished Marcel Duchamp. The presentation is structurally connectivist given its 4 directional presentation as a low laying sculpture. It is incredibly enjoyable. Plus the room is ringed with black haunting photograms called Angels by the fascinating Bruce Conner from 1973-75.

In terms of a more traditional synthetic associational curatorial fission, the strongest effect was achieved for me in the Ronald Bladen, Nancy Grossman, Cady Noland gallery. Everything here is screaming in harmony of power, sex and violence. The entire space felt hard as nails – most all of it a macho silver and black. Bracketing the huge gallery were long rows of Nancy Grossman’s famous black-leathered heads, aggressively sprouting phallic shapes like picks and horns. Ronald Bladen’s 1969 minimal masterwork The Cathedral Evening aggressively dominates the interior space with a mammoth triangle breach. This is backed up by his famous Three Elements from 1965. Then, giving the gallery a sense of an almost palpably Oedipal contest, is a large group of superb black on silver Cady Noland anthropological silkscreens on metal from the early 1990s.

Fig. 2: Ronald Bladen, Three Elements

The other room that really collectively worked for me held Paul Thek and Emma Kunz. Three wonderful Paul Thek Meat Pieces are there; weird post-minimal sculptures that sickly encase flayed body sections in wax in long yellow transparent plexiglas shrines that literally shine. This meat-machine mix is counter-pointed with the healing magnetic-field ephemerality of Emma Kunz’s geometric drawings, done with lead and coloured pencils or chalk on graph paper. It was easy to envision some fierce spiritual forces zapping each other throughout that area.

Other rooms bring the connectivist bent to a jolting halt. I simply admired Martin Boyce’s huge neon sculpture (Boyce channeling Dan Flavin), but it produced no associative effects with the rest of the room. Worse of all was a room entirely devoted to the work of Joe Brainard. What was that doing there? One strains to see (or imagine) even a 2nd mind in that space. So the unavoidable thought arises: Rondinone must like this stuff – so that is at least two minds in synch. But does Rondinone think there is anything still interesting in a Gober sink? His The Split-up Conflicted Sink from 1985 also played a huge flat note for me in this supposed visual symphony, as did the overly unembellished black crosses of Valentin Carron, the stupid car bashed installation by Sarah Lucas, and the cloying faux-naïve canvases of Karen Kilimnik. How to connect this boring and naïve work to the third mind connectivity theme?

On thinking about the show on my way home, I concluded that the show’s relationship to connectivity is gravely naïve and passé (if pleasant in a quaint, charming way) in lieu of the multi-networked world in which we now reside. By now various theories of complexity have established an undeniable influence within cultural theory by emphasizing open systems and collaborative adaptability. One ponders if Rondinone has ever even heard of the theories of Tiziana Terranova, Eugene Thacker or other cultural workers involved in the issues of human-machine symbiosis as interface within our inter-network media ecology. So yes, part of the pleasure for me was bathing in this old fashioned naivety, having just spent some serious time reading and writing on the topics of conspiratorial shadow activities, and viral software logic based on complex inter-connectionism. Placed against issues of avant-garde cybernetics, the coupling of nature and biology via code, media ecologies, distributed management teams, internet mash-up music, artificial life swarms, the political herd mind, and Negri/Hardt’s multitudes, THE THIRD MIND played in my mind like a romp through a kindergarten playpen. Nice. It felt good to forget about that pervasive nagging political/cultural feeling of stalemate created by the resilience of our current reality in that it assimilates everything.

But no, Ugo Rondinone did not randomly cut and reassemble art to create a new third meaning. He did not cut-up anything. He did, like every music DJ, fashion designer, and group show curator, remix contemporary expression from recent decades to permit new meanings to emerge from the mix. The ideas in the collaborative work of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs were not needed to achieve this end - and perhaps they were poorly intellectually served here (even though it was great to see the work). There was no use of chance or randomness evident here (even the re-shuffled catalogue pages I heard was rather suspiciously non-random) that is necessary for a really unexpected – and perhaps disastrous – result. This show did not go that far. There was no random reassembling of various fragments of something to give them a completely new and unexpected meaning (as I saw in the show Rolywholyover: A Composition for Museum by John Cage at the Guggenheim Museum in Soho NYC in 1994). THE THIRD MIND is just a standard, but good, heterogeneous art show where the whole is greater than its parts.

Which is as it must be.

Joseph Nechvatal http://www.nechvatal.net

LINKS

Cut-up sound recordings can be heard here: http://www.ubu.com/sound/burroughs.html

There were also a number of cut-up films that were produced which can

be seen here: http://www.ubu.com/film/burroughs.html

- William Buys a Parrot (1963)

- Bill and Tony (1972)

- Towers Open Fire (1963)

- Ghost at n°9 (Paris) (1963-72)

- The Cut-Ups (1966)

My review of: IF/THEN - A Book Review of “Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses” by Jussi Parikka here: http://transition.turbulence.org/blog/2007/09/28/review-of-digital-contagions/

You may wish to put my text into the cut-up machine on the web here: http://www.languageisavirus.com/cutupmachine.html

Joseph Nechvatal presently teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York City (SVA) and at Stevens Institute of Technology. His computer-robotic assisted paintings and computer software animations are shown regularly in galleries and museums throughout the world.