Scan Magazine: 2006-06-18

Contemporary Slumber

Daniel Kojta, PELT Gallery 2006

Sleep is an increasingly privileged site, a kind of last frontier around which the cameras have a tendency to hover. From Andy Warhol, to Chris Marker, to Bill Viola, and even to Big Brother, there's a fascination with watching people sleep, as if one day there will be a breakthrough, something remarkable to see, some secret slippage granting entry to that altered state of consciousness of seeing what 'we', as a collective, are dreaming. From our own subjective experience of dreaming [and active remembering], of seeing pictures and movies in our own heads, we register when the metaphoric cameras are on internally, in our own minds, even when asleep. Occasionally, the extra-perceptual track of dreams hasn't been automatically wiped in the morning.

However, looking on, at sleepers, from the outside, the cameras rolling, in probe position, there rarely is anything to see beyond snoring and restlessless; Bill Viola's awkward and unattractive sleeping in The Passing is more fitful and prosaic than Warhol's more poetic, but equally solo dandies, languishing in the technological version of Romantic painting's sleepers. Anne Girodet left Endymion Asleep in naked rapture; the youthful male body in abandon, sheets asunder, ravished by the viewer's eye, while a hazy nimbus of radiant light suggested the deeper contentment of dreams. Watching sleepers is a trope of limit, in which the other's alterity is never more present, alive and proximate in the teasing absence of access to the other's unconscious.

We all know we go somewhere when we sleep, and dreams are evidence that the camera in the head, through which Bergson described consciousness and perception, is always on. Why then is there this amnesia; the morning tape mostly black? Chris Marker's Le Jettee perhaps went furtherest in depicting a future post-holocaust state in which the interrogators of the future probe the sleep state for evidence of the past. Under hypnosis we can dredge up speech, and under general anaesthetic words can pour in a tirade impossible to hold back. But tapping directly into the images of sleep eludes the cameras, and even Marker's science fiction only recovered independent frames of photogrammes, as if to mark the idea of the struggle to recover images amid the fitfulness of the shifting layers of sleep.

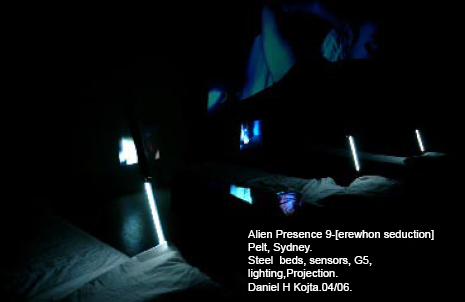

Daniel Kotje's installation Alien Presence – [ erewhon seduction ] at Pelt gallery in April bathed the space in projections of multiple sleepers. By day, in viewing time, the whole room breathed across and around the empty beds, where, by night, he had relays of sleepers, three at a time, pooling their collective sleeping states while the cameras collected independent 'sleeps'. There's a power in multiple sleepers, and the idea of collective dreams. Even if, as we all know, the camera never manages to capture the imperceptible, still some glimmer of that imperceptible world beckons. There's a quasi consciousness of the point of becoming-imperceptible, a liminal zone where our imagination goes to work and we almost see, but never do. (Do Marker's increasingly rapid progression of individual photogrammes of a woman sleeping accelerate to the point of transition to cinema's moving image, and signal this change of state - of 'seeing' the past - given that at that moment the girl opens her eyes?)

Under a key tone of blue, the 'sleeps' of Kotje's sleepers flicker through their dematerialized state of projected light as the condensed version of a more ethereal higher state beyond perceptual grasp. That the image is of sleeping, of multiple sleepers, matters, as if they were a lens or an energy channel to some higher form of seeing. Images of hills or lakes, or everyday traffic and people, turn us back towards the real. But sleeping and the association with the material presence of the sleepers' beds pushes against the limit of seeing; we want to see beyond the immaterial images of the prostrate bodies of the sleepers, and let the force of their collective sleeping bump us up one step higher on the immaterial plane. Like meditation, there's a structure to the breathing in the sleeping, which might just possibly trigger a shift in our own brainwave states.

Architect Jean Nouvel had already experimented with mixing the states of cinematic projection and sleeping by projecting full-scale cinematic movies onto the ceiling above the beds where people sleep. Like the wicked queen in Barbarella who sleeps in the chamber of dreams, Nouvel's projections saturate the darkened bedrooms and sleepers drift off bathed in the immaterial ghostlight of cinema's 'dreams', with the suggestion of the merging of two dreamstates. Kotje magnified this power nightly, accumulating projections, as his sleepers rotate - a rollcall of artists and visionaries from Stephen Barrass to Adam Cullen agreed to surrender their sleeps to the cumulative force of this project. If not dreams, a suggestive patterning of 'sleep force' or 'sleep breathing' collectively communicates from the zone of sleep.

Ann Finnegan is a writer living in Sydney.

Daniel H Kojta is a New Media artist utilising contemporary and antiquated technologies within 'immersive' installations that engage the audience in interactive environments. ON AIR Contemporary Art Studio is located in the Blue Mountains NSW.