This paper is an expanded version of “Judson Dance Theater and E.A.T.: ‘Utopian’ Collaborations in Sixties America”, which was presented at the conference e-Performance and Plug-ins: A Mediatised Performance Conference, held in December 2005 at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

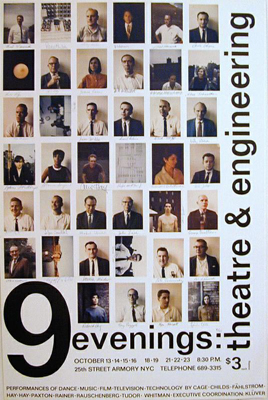

Figure 1: Poster for 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, 1966, designed by Robert Rauschenberg. Courtesy of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

This paper discusses a significant performance event of the 1960s titled 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. In 2006, MIT held an exhibition to mark the fortieth anniversary of this event, the first large-scale performance in the US in which electronic technology, and importantly, the working relationships between artists and engineers were central to its conception and actualisation. 9 Evenings created “an overarching electronic environment, a network that would connect the technical devices involved in the performances, an interface between the technical apparatus and the performers and engineers” (Bardiot 2005: 50-51).

Of relevance to a history of mediated performance are the new knowledges 9 Evenings produced about dancers' bodies and performance spaces within the context of an electronic environment. I would like to restore the historical specificity of these knowledges by focusing on two related aspects of 9 Evenings: the coincidence of the organisers' aims with those of the dancers who participated in it, and perhaps, the unanticipated outcomes of their particular view of materials – most notably that first material, the body – within the context of the wireless and audiovisual technologies used in 9 Evenings. I argue in this paper that it is the synergy of this view of materials and the nature of the electronic technologies of 9 Evenings that resulted in a representational expansion of the dancer's body that had not been seen before in American dance practice, although there were, as RoseLee Goldberg and Michael Rush detail in their histories of mediated performance, antecedents, such as Bauhaus performance (Goldberg 2001, Rush 2005). I also offer some exploratory remarks on the central role of sound in these works.

Live Events and Art-and-Technology in 1960s New York

I'd like to start by talking about the key players of 9 Evenings and their relationship to art practice in New York, and to larger cultural trends that shaped the artists' and technologists' approaches to the project.

Billy Klüver was a Bell Telephone Laboratories research scientist who had developed friendships with artists working in New York. The artist Robert Rauschenberg had worked with Klüver from 1962 to 1965 to develop his sound sculpture Oracle, which incorporated wireless radio into moveable components (Mattison 2003: 124). Klüver, who had been interested in avant-garde practice in art and film from his student days in Sweden, had assisted other artists in the early-to-mid 'sixties with projects requiring technical input. Klüver had helped Jean Tinguely, the Swiss kinetic-art sculptor, with his 1960 work, Homage to New York, which was designed to self-destruct during its ‘performance’ at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. For Homage to New York, Klüver and his colleagues at Bell Labs “constructed timing and triggering devices to release smoke, start a fire in a piano, break support members” (Klüver with Martin 2003: 22). Rauschenberg and Klüver first met in relation to Homage to New York, either during its construction (Martin 2007a), or at its opening (Mattison 2003: 123).

In the mid-1960s, Rauschenberg and Klüver organised meetings for their artist friends to meet engineers in order to discuss a project that would become 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. The 9 Evenings project originated as an invitation to participate in a festival of art and technology in Stockholm, although logistical and organisational difficulties and differences of opinion led to the project being mounted much closer to home (Loewen 1975: 64). Many of the dancers who had choreographed and performed earlier in the 1960s within the Judson Dance Theater were among the artists attending project discussion. The Judson Dance Theater, based at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, New York, was well-regarded among visual artists in the New York scene, and a small number of other cognoscenti, such as the Village Voice’s dance critic Jill Johnston. However, their choreographic works, which critically questioned the conventions of ballet and modern dance, were not then widely known. In the decades since the 1960s, as dance historian Sally Banes puts it, Judson has been recognised as “the seedbed for post-modern dance, the first avant-garde movement in dance theater since the modern dance of the 1930s and 1940s” (1993a: xi). It is likely that the Judson dancers knew about Klüver through Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg performed with the Judson Dance Theater for a few years in the early to mid-1960s (Banes 1987: 13), designed the lighting for some Judson concerts (Mattison 2003: 171), and had worked as lighting director and stage manager for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (2003: 169). Coincident with his work on Oracle with Klüver, Rauschenberg was also devising his own performance works, notably Spring Training and Pelican.

Artists were paired with engineers, often Bell Labs colleagues of Klüver's, who would work with the artists to address the technological needs of their projects. The result was 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, held at the 69th Regimental Armory in New York in October of 1966. The program included performances by dancers who had been associated with Judson: Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, and Alex Hay. Rauschenberg devised a performance involving a tennis game and infrared camera, and sound works were prepared by John Cage, the experimental composer, and David Tudor, who had been known as a performer of “often daunting new music…closely associated with Cage, Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff” (Kahn 199: 328). Also contributing performances were Robert Whitman, whose pieces at the Reuben Gallery several years earlier had been described as Happenings, although Whitman viewed his work as events that were theatrical in nature (Goldberg 2001: 128); and Öyvind Fahlström, who, like Whitman, saw his works as theatre pieces (Martin 2007a).

9 Evenings occurred at the start of what was to become a trend in the US toward ‘art-and-technology’ collaborations. There were at least ten such major events held in the United States between 1966 and 1972 (Shanken 1998), four in New York alone: 9 Evenings; Software. Information technology: its new meaning for art (at the Jewish Museum); The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (at the Museum of Modern Art); and Some More Beginnings (at the Brooklyn Museum). The latter two exhibitions were associated with Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), the organisation arising from Rauschenberg’s and Klüver’s efforts to bring artists and technologists together.

As the titles of these events suggest, American intellectual and cultural life of this period was characterised by the recognition that a threshold had been reached – the ‘Digital’ or ‘Computer Age’ was superseding the ‘Machine Age’, and instead of mimicking muscle the new machines would function like the human brain (Hultén 1968: 3). Along with the many art-and-technology-themed events of the period, and a growing awareness within the wider culture of changing technologies, particularly those of communication, information, and the media, forums on the question of the future proliferated (Lee 2004). The Guggenheim Museum's lecture series On the Future of Art explicitly linked the “crisis within contemporary art” (Fry 1970: vii) with the concern “of the culture as a whole with its own future, a tendency which has appeared rarely if ever before with its present intensity” (Fry 1970: ix). In this series, thinkers outside the New York art world, such as the behaviourist B.F. Skinner and Arnold J. Toynbee, a historian of the rise and fall of civilisations, were asked to contribute alongside notable art-world figures, as “the nature of the problem demanded fresh insights beyond the normal limits of critical and art-historical discourse” (Fry 1970: vii). This interdisciplinary turn indicated not only a willingness to investigate frameworks normally outside those of art in response to an urgent situation, but suggested that changing times required new ways of thinking across boundaries previously seen as rigidly drawn. The art-and-technology concept, as an exemplary interdisciplinary exchange at the frontier of new science, would have seemed particularly well positioned to creatively address problems of increasing significance to humankind.

Unlike the general tenor of the art-and-technology forays to come, 9 Evenings represented the convergence of several different streams of recent performance activity occurring in New York. Norma Loewen sketches a history for 9 Evenings, and E.A.T., within the context of live events and installation in New York of the late 1950s and early 1960s. As art historians such as Barbara Haskell, writing on Pop, Happenings, and Minimalism in New York, have stated, advanced practice at this time was not as differentiated as it would later become, and there was a good deal of crossover among artists (Haskell 1984: 51 and 65, Meyer 2001: 45). Simone Forti had first shown her dance work at a Happening (Forti 1974: 36), for example, and the contribution of sculptor and performer Robert Morris to the Fluxus volume An Anthology was the result of his friendship with artist Walter De Maria and La Monte Young, an experimental composer (Haskell 1984: 98). The other significant contributory strand to 9 Evenings – and one less remarked upon – was that of experimental and electronic music composition: Cage's and Tudor's embracing of distinctly “unmusical” sound, and, less obviously, Young's desire to “get inside” a sound, to experience sound as attenuated and enveloping (Young 1965: 81).

9 Evenings was also notable for its sheer scale. The Armory space had a vaulted steel roof 120 feet high at its apex and a floor area of 120 by 150 feet – an expansive space with poor acoustics (Whitman 1967: 28, Klüver 1979: 1, Klüver with Martin 2003: 32). Simone Whitman (Forti) stated that “the decision was made to stick with the Armory anyway” because “[t]he space itself was beautiful” (Whitman 1967: 28). 9 Evenings received considerable attention in the popular press as well as within the New York art world. Prior to its staging, Billy Klüver was interviewed in Life magazine (August 12, 1966) and as Whitman (administrative assistant to Klüver for 9 Evenings) records in her journals of the event, interest was substantial, necessitating the rental of first 1,000, then 2,000 chairs per performance (Loewen 1975: 65).

Collaboration, the Work of Materials, Exteriorising Interiority

Rauschenberg and Klüver shared the view that collaboration facilitated between artists and engineers would establish new relationships for understanding and using technology, and that larger, societal goals were at stake in this endeavour. As Robert Mattison explains: “For Rauschenberg and Klüver, E.A.T. was not simply a practical way to bring artists and engineers together. It embodied a plan for a better world and a moral imperative in an otherwise troubled planet” (2003: 125). Klüver passionately believed that art had a role in humanising technology. In Klüver’s words, “artists had the intellectual freedom and sense of personal responsibility which could shape the new technology for the benefit of the individual” (Klüver with Martin 2003: 21). Klüver would eventually resign his position at Bell Labs to become the president of E.A.T., consistently promoting these objectives in projects over the next several decades (Tomkins 1976: 98).

Klüver’s focus was the relation between artists and engineers and art and new technology, rather than the question of bridging the perceived gap between art and science as such. Klüver began to consider how these relationships might work in a book tentatively titled Engineering in Art that he began to draft in 1965, after assisting Cage with his piece Variations V (Loewen 1975: 40). Klüver felt that art and science were quite different human undertakings that could not be “brought together” (Martin 2007a). In the Engineering in Art draft, Klüver wrote:

It is hard to think of two professions with such great dissimilarities as the artists and the scientists. … I feel like a man standing with one leg each on an icefloat [sic]. The icefloats are drifting apart and I will end up with the fish. C.P. Snow cornered the market with his “two cultures.” Art and technology, art and science are not two cultures, they are two separate worlds speaking two entirely different languages (Loewen 1975: 41).

Loewen positions Klüver’s theorising at this time, as expressed in Engineering in Art, as the source of inspiration for the event that became 9 Evenings. Klüver saw the Stockholm festival “as a possible impetus for realising what a book could not and became in charge of the American contribution to the project” (Loewen 1975: 46).

I would like to further Loewen’s argument by asserting that these ideals of Klüver’s concerning the way such collaborations could work, articulated in the lead-up to what became 9 Evenings, were of central significance to the nature of the 9 Evenings works. In the Engineering in Art drafts, Klüver wrote “'At present techniques have been established by [Claes] Oldenburg and others to “use” the specific character of human beings as part of the work of art. Thus the process by which the engineer can be used is part of contemporary art'” (Loewen 1975: 41). As Klüver felt that “most artists would and could use technology if given access to it” (Loewen 1975: 41), in this statement he was probably intending to encourage artists to consider using technology by framing it as consistent with contemporary practice. Loewen pithily summarises Klüver’s point: “The engineer was considered another material for the artist who would be used as such” (Loewen 1975: 41). In a talk given on January 28, 1966, in the beginning stages of work on the American contribution to the Swedish festival, Klüver linked this way of working to larger goals to underscore the significance of his conception of the artist-technology relationship: “What I am suggesting is that the use of the engineer by the artist will stimulate new ways of looking at technology, and of dealing with life in the future” (Loewen 1975: p. 45).

Rather than considering Klüver’s and Rauschenberg’s stated aims in terms of a utopianism that has been seen by art historians to typify art-and-technology collaborations of the American ’sixties, I would like to explore the significance of Klüver’s and Rauschenberg's view of the artist’s 'use' of 'materials'. In Klüver’s model of the artist-engineer relationship, the engineer would facilitate the artist’s vision and open new possibilities for the artist to consider. Klüver stated “This new availability was largely responsible for the size and complexity of the machine”, referring to his work with Jean Tinguely on Homage to New York (Klüver 1961 in Loewen 1975: 17). In this view, the new possibilities that might extend or modify the artist’s conception, or the work-in-progress, would be to do with the nature of the ‘machine’ itself – the inherent characteristics of the totality of materials available to the artist, including the engineer as much as the physical components employed in the work. The artist must by necessity work in "total anarchy and freedom", although the fruits of the artist’s labours would be, paradoxically, the result of the very limitations – and enabling attributes – of their materials. As Rauschenberg had said of his piece Pelican, performed on roller skates while wearing a parachute on his back, “'It was a using of the limitations of the material as a freedom that would eventually establish the form'” (Kostelanetz 1968: 82 in Loewen 1975: 26). The artist would see, as the result of this work through and on materials, new possibilities for society’s use of technology that the engineer could not identify alone. Rauschenberg did not specifically link the artist’s working methods with technology to the larger aims he and Klüver supported, in the way that Klüver had. However, no doubt related to his own approach to materials, often heterogeneous, Rauschenberg too saw the technology used by artists in 9 Evenings as a material that would necessarily shape the performances: “I think just the experience of dealing with these kinds of material that have this particular character is probably going to end up being an enormous influence on the work esthetically” (Whitman 1967: 27).

The Judson view of technology as such was much the same as Klüver’s, though for differing reasons. Technologists would be used as materials by artists, whose vision they would help realise, as Klüver might have said. Of greater relevance to the artists formerly working in the Judson group was that “[t]echnology offered an objective rigor that was a welcome antidote to the subjectivity of dramatic dance, and a logical extension of a concern with methodology” (Banes 1987: 14). Judson dance was noted for a certain coolness, an attitude that shared affinities with the tendency in advanced art of the first part of the 1960s toward neutrality – the “disavowal of expression”, as James Meyer has put it, referring to the characteristic approach of Pop and Minimalist practitioners (although their work may not have borne either style label at the time). Countering Abstract Expressionism's gestural language, “artists from both camps developed techniques that threw the transparent representation of emotion into doubt” (Meyer 2001: 47). Likewise, Judson dance sought to distance itself from the conventions of expressivity and loaded emotion that typified modern dance and ballet, instead looking toward externally imposed and aleatory structures to progress movement through time. These technologies would also allow the Judson performers to extrapolate from their usual practice. The limitations and strengths of technologies available in 9 Evenings would play a similar role in structuring and isolating movement as had the frameworks of tasks, games, rules, and schematic grids with which Judson work had been consistently preoccupied. Judson dances often mediated movement through materials, including representational media, as in Paxton's Proxy, whose movement score was a collage of “sports photographs and other posture imagery” (Banes 1987: 59). Similarly, in Geranium, Childs used a taped radio broadcast of a football game that seemed to provoke her movement activity (Banes 1987: 135). Rainer read texts, used a variety of objects and props, and reused segments of her own work in later works, a strategy Carrie Lambert relates to Rainer's particular interest in media and mediation (Lambert 2002). These performers would have regarded the inclusion of the new technologies in terms of their qualitative contributions – to be worked with and around as materials with unique properties, similar to the way that they worked with wood planks, rubber balls, stairs, mattresses, texts, voice, and bodies.

To understand the Judson dancers’ treatment of materials in the 9 Evenings situation, it is also useful to consider the improvisational strategies taught in dancer Ann Halprin’s 1960 summer workshop, which was attended by Rainer, Forti, Trisha Brown (whose early choreography was also associated with the Judson Dance Theater) and experimental composer La Monte Young, among others. Halprin's approach, which relied on the use of tasks, sound, and natural objects to initiate and structure dance movement, influenced Forti most directly (as Forti had studied with Halprin since the mid-1950s), Rainer, and others who would form the Judson group (Forti 1974: 29, Ross 2003: 50, Banes 1987 and 1993a, Goldberg 2001: 140). In a 1965 interview with Rainer, Halprin said, “We would isolate in an anatomical and objective way the body as an instrument” (Rainer and Halprin 1965: 143). This reconsideration of the body was intended to counter habitual movement, the “repetition of similar attitudes that didn’t lead to any further growth” (1965: 144). Halprin also felt “systems that would knock out cause and effect” were necessary, enabling her (and her students) “to find out things that I’d never thought of, that would never come out of my personal responses” (1965: 144). Forti stated there was much talk in Halprin’s classes of “expanding our movement vocabulary”; the body’s responses to a stimulus or an idea would be explored, and the body “would come out with movement that went beyond plan or habit” (Forti 1974: 29). In her interview with Rainer, Halprin referred to “a desire to find out more about the human interior”, to investigate “feelings” and the “subconscious”. Getting at this was a “technical problem”, and the feelings that arose in improvisation became a useful “new material” (Rainer and Halprin 1965: 163-164).

According to dance historian Janice Ross, Halprin’s improvisational techniques were “a means for physicalizing intuition, for giving feeling a physical form”, a view that would be “refuted” by Rainer, Forti, and Brown, Halprin’s most influential students (2003: 50). After having seen Halprin’s finished work, Rainer would later comment that she was surprised at its comparatively traditional and theatrical quality, which she found quite unlike the radical experiments of the workshop (Ross 2007: 147 and 151). What interested Rainer was the “pre-performance stage she encountered in Ann’s workshop”: in her own choreography, Rainer would take “the exercises involving the unadorned execution of movement tasks as finished performance material” (2007: 151).

For Forti, and particularly for Rainer, Halprin’s approach to feeling in movement work was taken up as the mining of interior material, a neutral manipulation of otherwise emotive or autobiographical content. Jill Johnston, a dance critic who enthusiastically reviewed Judson performances for the Village Voice through the 1960s, described in a 1964 review Rainer's “screaming tantrum” in Three Seascapes as “an exciting abstraction”. In this review, Johnston aptly wrote, “She doesn't mean it, or pretend to mean it, the way older modern dancers did. She's presenting emotions as facts and not as idealized commentaries on the human condition” (Johnston 1964: 45). This view of interiority was that of a repository of “material” that could be externalised through the body's own processes for objective consideration. This material, like any other material Judson dancers may have used – a ball, a picture of a baseball player, a plank, a pear, and, in 9 Evenings, tape recorders, transducers, projections, wireless control – was available for manipulation in performance.

I argue in this paper that the representations of the performing body invented in the dancers’ works of 9 Evenings were directly related to the way this treatment of materials and processes – in coincident agreement with Klüver’s formulation of the artists’ engagement with technology – was mediated through the particular attributes of 9 Evenings’ electronic environment.

Electronic Technologies and the Performance Environment

As Simone Whitman recalls, scoping the Armory facility in August for Klüver to determine whether the wireless radio system would work, “The building wasn’t going to shield us from interference. On the contrary, it was acting as a great antenna, bringing us all kinds of extraneous signals. I called Billy from the Armory phone booth. He said the engineers would deal with it somehow” (Whitman 1967: 28). Klüver and the engineers recorded a six-second reverberation in the Armory space, and ambient noise seemed to dominate the acoustic environment, blotting out sound local to the listener (Klüver 1979: 1). As Klüver recalls, “when everyone was working during the set-up, the ambient noise was such that you couldn’t hear what people were telling you 10 feet away” (Klüver 1979: 1). Deborah Hay’s treatment of composer Ichiyanagi Toshi’s Funakakushi would exploit this quality, its sound passing across the space as a sourceless “cloud”. Cage would use the Armory's tendency to draw sound in, and Tudor's work would play with its extended reverberation time. Other works, such as Whitman's, took advantage of the effects of loudness in this acoustical environment (Martin 2007a).

The use of wireless technology was central to the 9 Evenings performances. As Klüver put it:

The wireless is like the crown of the whole thing. There’s nothing like it that exists on the market. Actually what we’re doing is putting radio in the theatre. We asked the FCC [Federal Communications Commission] for 15 frequencies for continuous performance between the 13th and the 23rd of October. This is really much more fantastic than anything else that has been done (Klüver 1967a: 28).

The wireless system formed a core element of TEEM, an acronym for Theatrical Electronic Environmental Modular system, according to Per Biorn (Martin 2006), the engineer who worked with Yvonne Rainer on her 9 Evenings performance ‘Carriage Discreteness’. TEEM was a purpose-built modular control system whose elements, arranged in different configurations for each artist's piece, allowed for centralised control (2006). Bardiot states that the wireless “effectively prefigured the foundational principles of TEEM” in the sense that it created a network, an electronic environment (Bardiot 2005: 50-51) in which performance would occur. The 9 Evenings artists, given their backgrounds in Judson dance and experimental theatre and music, would have been used to performing in spaces exceeding that of the “proscenium arch”. Likewise, in Judson dance concerts, experimental theatre pieces, or music concerts associated with Fluxus, such as those Ichiyanagi organised for Cage and Tudor in Japan (Munroe 1994: 217-218), events occurred outside the thematic and narrative structures of more traditional forms of theatre, instead favouring strategies of acausality, dissociation, and simultaneity. I suggest that these strategies formed the performative correlate to an electronic environment well suited to simultaneous, discontinuous, apparently uncaused activity (no wires, no apparent triggers).

While the performance space in 9 Evenings was of course not “networked” in the sense of this term within contemporary digital culture, Bardiot’s observation suggests the centrality of the wireless to the conception of the works themselves as interconnected arrays of technologies, physical space, performers, and, for some of the performances, spectators. In this sense, the networks created in 9 Evenings can be seen as matrices of equivalent performative possibilities. Events were the outcomes of possibilities only realised in performance, and these were associated with each other only by their arrangement in a schema that constituted the work. Within 9 Evenings’ technological field, the realisation of this schema would often (but not always) occur at a remove, by wireless or other remote controls, and, for the dancers’ works, through an electronic mediation of the body that was often mapped by sound.

The Extensible, Spatialised Body

I'd now like to discuss some of the 9 Evenings works, focusing on those of the Judson artists, but starting with Cage and Tudor, whose contributions most clearly focused on sound rather than body – although, as I'll indicate later, the spaces of sound and of body became intertwined. I'll introduce my discussion of these works with remarks from a talk Klüver gave at MIT after 9 Evenings, published in the E.A.T. Proceedings some months after his talk:

Sounds coming out of the body or other ways of representing the motion [of the body] also interest the dancer. For over four years, we have on several occasions tried to do something with the body sounds. Cunningham was one of the first to be interested. In a dance by Yvonne Rainer we had to settle for her breathing which was transmitted offstage, by an FM transmitter. The body is very quiet and you need elaborate equipment to pick up muscle potentials and brain waves (Klüver 1967b: 12).

For Cage’s work in 9 Evenings, titled ‘Variations VII’, Cage and engineer Cecil Coker set up an array of devices that included contact microphones attached to appliances, such as a blender and toaster; photocells mounted on the performance area that triggered sound outputs, as in Variations V, a work of the previous year for the Cunningham Dance Company, in which the dancers' movements cued electronic sound; one person (and perhaps more, depending on the report) “wired” to capture bodily sounds; and a number of open telephone lines connected to various New York locations including the restaurant Luchow’s, the Bronx Zoo’s aviary, and the New York Times press room (Klüver 1979: 5, Klüver with Martin 2003: 38). The audience was encouraged to walk around to experience sound within the space.

In his analysis of Cage and sound, Douglas Kahn associates Cage’s “famous visit to the anechoic chamber, where he heard the ever-present sounds of his body, the low sound of his blood circulating, and the high-pitched sound of his nervous system in operation” with his interest in amplification devices and related technologies (1999: 158). Through these investigations, Cage extended musicality to all sounds one could hear, and came to feel there always is sound, even if we cannot hear it. Cage would “rhetorically use the promise of technology to extend all sound and always sound outside the operations of his body to hear the vibrations of matter” (Kahn 1999: 158-159). Cage structured his 9 Evenings work to capture all of New York as sound – or, rather, the possibility of capturing all of New York as sound: the sounds of the body's microcosm, those of the small and local, and the sounds of activity outside the Armory. ‘Variations VII’ suggested these worlds as metaphors for each other through their shared function as sound source: their sounds, made equally available for audition, mixed in the space to provide for listeners the whole sonic spectrum.

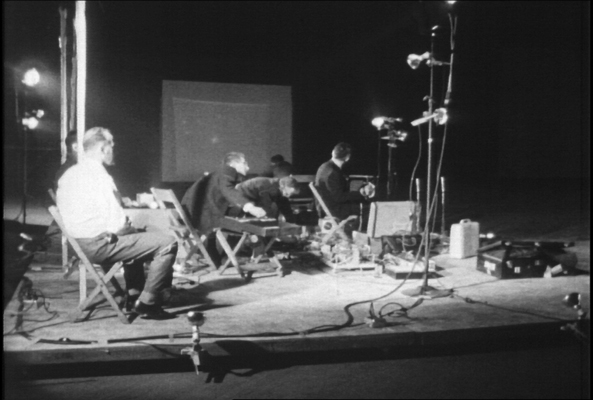

Figure 2: Frame capture, 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, 1966, “Bandoneon ! (a combine)”, camera: Alfons Schilling and Bell Labs Engineers, produced by Billy Klüver, 16mm black-and-white film. Courtesy of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

David Tudor contributed ‘Bandoneon ! (a combine)’ (where the ‘!’ is the mathematical sign for factorial, not an exclamation mark). Engineer Fred Waldhauer’s complex electronic system situated the processed sound of a bandoneon, a concertina-like instrument, at the centre of a network of sound, lights, and projectors. While the lengthy echo of the Armory space posed problems for some of the artists, “Tudor worked with this long reverberation time” (Klüver with Martin 2003: 36). The bandoneon’s sound was distributed to several processing devices, including a “processing circuit” that Tudor built; this device was, in turn, linked to four transducers (2003: 35) attached to “instrumental loudspeakers” Tudor had constructed of wooden planks, plate glass, a steel tray, and aluminum sheets, which moved about on the Armory floor on radio-controlled carts otherwise used for Deborah Hay’s piece (Driscoll and Rogalsky 2001: 3). The instrumental loudspeakers were intended to produce sound specific to the resonant characteristics of their materials. Tudor had been interested in “resonat[ing] physical objects” since 1965, the year before 9 Evenings (2001: 2).

Klüver has discussed ‘Bandoneon !’ as “in effect us[ing] the entire Armory as his [Tudor’s] instrument” (Klüver with Martin 2003: 36, also mentioned in Klüver 1979: 4). Catherine Morris has likewise commented that in ‘Bandoneon !’, Tudor “sought to turn the Armory into a musical instrument activated by a single musician” (2006: 18). Morris relates ‘Bandoneon !’ to Tudor’s “earlier experiments in transforming a piano into a singular orchestral entity by inserting various objects into the instrument’s string structure”, thus turning the bandoneon “into a central control unit” (2006: 18). The Tudor literature suggests, however, a reversal of these terms: that instead of centralising an “orchestra” in a single “instrument,” Tudor saw the “instrument” as a dynamic system composed of heterogeneous parts and behaviours, including its own feedback. I suggest the meaning of Klüver’s remark derives from this aspect of Tudor’s early compositional practice. ‘Bandoneon !’ was one of Tudor’s earliest live performances of one of his own compositions. He had been primarily known until then for his “realisations” of Cage’s and other composers’ works. Tudor’s realisation of Cage’s Variations II for amplified piano, recorded in 1961, revealed an interest in the totality of sound produced: as Richard Teitelbaum has explained, in Tudor’s realisation of Variations II, “the total configuration would be regarded as the instrument”, and “[t]herefore, any sound generated in the system (such as audio feedback) would be accepted and utilized in the performance” (Teitelbaum 1961: unpaginated). James Pritchett links Variations II to ‘Bandoneon !’: “While the specific systems and performance situations of Bandoneon! and Variations II are quite different, the underlying compositional approach is the same” (2001: 9).

The compositional strategy typifying Tudor’s early works, including ‘Bandoneon !’, was one of “the design of a complex, uncontrollable electronic instrumental system that must then be explored through performance” (Pritchett 2001: 9). As such, Pritchett states, the emphasis in Tudor’s early compositions was on the performer’s “action” rather than perfection of “results”. In Tudor’s Variations II, multiple interactions among sound channels that included microphones and loudspeakers created a complex performance situation in which the performer had to flexibly adapt to changing sonic conditions as “sounds merge, overlap, and run into one another in waves of feedback and reverb” (2001: 8). Michelle Kuo describes ‘Bandoneon !’ similarly: “a web of sonic and visual effects exponentially distending in time” (2006: 32). In ‘Bandoneon !’, “[t]he multiple layers of processing and switching prevented Tudor from being able to completely control it, so that his performance took the character of an exploration of the possibilities presented” (Pritchett 2001: 9).

Although the actions and effects of their 9 Evenings works were quite different from those of Tudor’s, the Judson dancers’ view of materials that I’ve outlined earlier bore striking similarities to Tudor’s desire to explore the particular properties of physical objects and systems in action. And if ‘Bandoneon !’ was an exploration of performative possibilities, it was well suited to the strengths of 9 Evenings’ technological network, which we have discussed. I’d like to make one further point about the behaviour of systems considered performative totalities – in itself a concept central to electronically mediated performance since its first manifestation in 9 Evenings. The scope and complexity of sound in ‘Bandoneon !’ would suggest a limit to what the audience could have ‘known’. For Kuo, ‘Bandoneon !’ demonstrated, more than anything else, an “insurgency of effects, one’s inability to take in the work as a whole” (2006: 32). We will return to this point about the audience’s partial knowledge of the performance of complex systems in discussion of works by Lucinda Childs and Yvonne Rainer.

Steve Paxton’s work ‘Physical Things’ was described by Paxton in the 9 Evenings program as a “dance with a set” (Paxton 1966a: unpaginated). The audience entered room-like spaces constructed of transparent polyethylene, linked by a large S-shaped tunnel. From the last room a transparent, 100-foot-high tower rose, “with white noise pouring down from above”, as Klüver recalls (Klüver 1979: 2). Although performers danced in the rooms of the plastic structure, perhaps as if it were a set, Paxton's notes reflecting his early thinking suggest the work was, rather, conceived as a site for materialisation of disembodied sensory effects. His notes ask “can sound ‘materialize’ in a space at different discrete points? without speakers? can the surrounding area be silent? could images, smells, or matter be ‘materialized’ in this same way?” (Paxton 1966b: unpaginated). It was possibly easiest to effect such a “materialization” with sound. Leaving the polyethylene structure, visitors were given hand-held units that picked up signals from wire loops fastened overhead in a net. They could hear different recordings depending on their position in relation to the wire loops: jungle birds, readings of the Song of Solomon, self-hypnosis instruction on how to quit smoking, and Mahler’s Songs of the Earth (C. Morris 2006: 16), among other sounds and vocals.

Sally Banes describes ‘Physical Things’ as one of several works by Paxton featuring “huge, transparent, plastic inflatable tunnels” (1987: 62). Beginning with Music for Word Words (1963), which involved a plastic “room” that deflated to become a human-sized costume, these works explored a confusion of the textures of plastic and skin and of scale and function, Banes states (1987: 62). Like Paxton's "100-foot plastic tunnel" in a work of the previous year, The Deposits, the S-shaped tunnel of ‘Physical Things’ was “analogous to human intestines, adding another type of confusion... – that of interior and exterior” (Banes 1987: 62). Through its manipulation of scale, the work positioned body-space in a metaphoric relation to larger spaces, as the Cage piece had similarly occasioned through sound. The structure seemed to encompass architectural space, domestic space, and the space of the body, but as indistinct or overlapping categories. Doris Hering, who reviewed 9 Evenings for Dance Magazine, noted that the clear polyethylene walls of the tunnel “heaved and trembled” (1966: 37): an uncertain, insubstantial architecture. As in Music for Word Words, the plastic rooms of Paxton’s structure in ‘Physical Things’ deflated to approximate organic forms. When the structure was dismantled, it “slowly collapsed...resembl[ing] beached jelly fish” (Hering 1966: 38).

Simone Whitman interviewed many of the performers as they were first considering their works, and kept a journal documenting the development of 9 Evenings. In an interview dated April 11, 1966, Childs discussed her interest in creating dance works that would function through what she termed “translation”, a shift from one kind of action or process to another between otherwise unrelated elements. The use of a sonar beam in Childs' piece ‘Vehicle’ was determined at a meeting in response to her idea: “sensitizing movement and making a…or visual or sound or any kind of interpretation or translation of what happens under different kinds of stress or energy, I used that as a possibility, they came up with this idea which I accepted” (Whitman 1966: 13; ellipsis is Whitman’s).

In ‘Vehicle’, Childs swung three red fireman’s buckets containing light bulbs within a scaffolding structure, cutting ultrasonic sound beams created by transmitters installed in stands inside the scaffold. The frequency of the signal reflected by the buckets back to the Doppler sonar receiver was related to the speed and direction of Childs’ swinging. The result of the original, ultrasonic signal mixing with the reflected signal was audible sound, which was transmitted to speakers positioned around the Armory space. The sound, a “swishing noise like wind blowing through a forest”, was processed to generate video images projected onto a large screen (Klüver 1979: 6). These visuals and the lights in the buckets were turned on and off in relation to sound from a radio station, which the audience could not hear (Klüver 1979: 6).

In her statement for the 9 Evenings program, which sounded remarkably similar to Rauschenberg’s comment that materials used in 9 Evenings would shape aesthetic results, Childs described her ideas as “generally derived from the laws which govern the materials themselves and I attempt to allow the qualities and limitations of materials to be exposed in different situations” (Childs 1966: unpaginated). As Catherine Morris explains, in Vehicle, “Childs’ interest in extrapolating dance movement…was transferred to normally invisible electrical transmissions and mundane objects, effectively illuminating the corporeal medium of sound waves” (2006: 11). We see Childs' interest in qualifying performance activity in relation to materials earlier, in Geranium, and in her well-known piece Carnation (1964), in which she manipulated ordinary objects such as a colander, hair curlers, sponges, and a plastic bag, forcing the soft curlers and sponges into her mouth. As in Cage’s work, and Alex Hay’s, which we will shortly discuss, Childs attempted to reveal that which is otherwise not available to perception. Further, Childs wanted to create a situation whose product would be the result of both the intrinsic nature of objects – the buckets – and her movement action on them. Robert Morris described this relationship in an essay of 1970: “The body's activity as it engages in manipulating various materials according to different processes has open to it different possibilities for behavior” (1970: 62). Morris was speaking of his own works, at that time having moved away from Minimalism, but his ideas on process and materials shared affinities with those that had characterised Judson works.

In Deborah Hay's piece, ‘Solo’, an ensemble of performers dressed as musicians sat to the side of the space, operating remote-controlled platforms carrying performers in white costumes who walked or rode according to specific rules. Hering wrote in her review, “The total effect was of trying through activity to create a moonlike atmosphere of impassivity” (Hering 1966: 38). Hay had wanted a “white, even, clear event in space” whose elements were “equal in energy and visibility” (D. Hay 1966: unpaginated). This statement can be seen within the context of the Judson interest in a certain cool regard, an uninflected progression. In Rainer's essay on what would become her signature dance work, Trio A, a dance noted for its steady pulse, its one-thing-after-another quality, Rainer wrote of Trio A's evenness of “energy distribution” (Rainer 1968). Although Rainer and Hay would consider “energy” rather differently in their later work, we can see a common interest at this time, as in Childs' ‘Vehicle’, in the energy commensurate to a particular activity, and the movement of energy between forms and processes.

The sound piece for Hay's work, Ichiyanagi Toshi's Funakakushi, “originally an 8-channel work composed for eight outdoor stone speakers on Shikoku Island”, was intended as a cloud of sound that would move and gradually dissipate as the radio-controlled platforms rolled evenly through the space. Klüver: “Deborah Hay described the effect she wanted, ‘The sound had to travel, it needed space to flow and disappear. The source had to be dispersed and undefined’” (Klüver 1979: 3). To achieve this effect in the Armory, David Tudor “played” the photocells of a proportional control board with a penlight flashlight. That this undefined sound-shape was the counterpoint to ‘Solo’'s even, regular movement activity suggests a parallel structuring similar to that of Alex Hay's 9 Evenings work, ‘Grass Field’.

Alex Hay described ‘Grass Field’ as consisting of three different processes “equal in time”: the sound broadcast, the “skin-tone” costuming of performers, and a “singular work activity”, the patterned placement and retrieval of sixty-four numbered six-foot squares of canvas by Robert Rauschenberg and Steve Paxton (A. Hay 1966: unpaginated). Hay was seated in the centre of the array of cloths, and an enlarged image of his face was projected behind him from a camera placed in front. Like the use of electrodes in Cage's ‘Variations VII’ to capture body sounds (Martin 2007b), Hay’s body was studded with electrodes to pick up the sounds of muscle activity, eye movements, and brainwaves (Klüver 1979: 2). These were connected to a unit attached to his back that transmitted the sounds to the control booth, from where they were broadcast. Klüver comments that the engineers had to be quite innovative to build a battery-driven amplifier in 1966 small enough for Hay to wear (Klüver with Martin 2003: 32).

Two years earlier, as Klüver had mentioned in his talk at MIT, Klüver and his Bell Labs colleague Harold Hodges built equipment for Yvonne Rainer’s solo dance At My Body’s House (Sachs 2002: 136-137, Rainer 1974: 295) to pick up and broadcast the sound of her breathing. Rainer wore a contact microphone at her throat and a small wireless transmitter at her waist, which relayed sound to a speaker (Klüver with Martin 2003: 24). Rainer stated that she began the dance by standing still for three minutes while loud Buxtehude organ music played, followed by “small, rapid footwork” (1974: 295). “At one point I told a story about an elephant from The Diary of William Bentley used in Parts of Some Sextets,” Rainer later wrote (1974: 295). As Rainer has explicitly indicated where the music element occurred, we might assume that the audience could hear her breathing during the “rapid footwork” section. Her breath and throat sounds would also have been audible during the elephant story. Where Judson work occurred in relative silence, or did not use music sufficiently grandiose or loud enough to call attention to itself – as Rainer describes the Buxtehude here, and as she used Berlioz’s Requiem in her 1963 piece, We Shall Run (Rainer 1974: 290) – there was still the production of sound, from actions on objects used, and of the dancer's body itself in performance. In the small space of the Judson Church, the audience would have heard the sound of performers’ breathing and footsteps clearly. In At My Body’s House, Rainer attempted to create what she must have felt was a similar effect, amplified to meet the demands of the space to hand. The Judson dancers' strategies of quotation and methodological transparency would suggest they were also interested in the sound of breathing and footwork as the legible traces, or indexes, of the dancers’ movement, or, rather, their “energy distribution”. These sounds are traces that point to the body. Here, because the body could be “seen” to visibly produce these sounds, they were likely to have been understood by the viewer as located within the body before them. Amplification, such as we see in At My Body’s House, would have estranged sound somewhat from the body producing it, but there would nonetheless have been a perceived relation between the trace and its source.

Sound in the 9 Evenings works, on the other hand, was increasingly estranged from the performer’s body: through transformations and amplifications effected by electronic technologies, the relation between the body’s externalised product and the body was no longer clear. The body was conflated with the space into which it was attenuated through its mediated issue. This conflation was more than simply an expansion of known sensory response. Works such as Paxton’s, Childs’ and particularly Alex Hay’s demonstrated a new complication of the sensory, and of proprioception, to which electronic mediation now gave rise: what are the limits of the proper body when it is no longer marked at its physical periphery by the natural work of the senses?

Another effect of this re-presentation of the performer’s body was a confounding of what in performance studies is termed the “live” and the “mediated”. I would like to restate this observation in terms of my discussion of the 9 Evenings’ artists’ view of materials: as a simultaneous (and unacknowledged) emphasis on the body’s materiality and its abstraction. The body represented in Hay's work was highly material because, through its own inner workings, it generated sound and vision intrinsic to its nature, the incontrovertibly contingent trace of this particular body's interior, which could not be seen. It was simultaneously abstracted as a productive machine that generated representational effects while its own visibility was diminished. This abstraction was to do with the idea of translation we have seen in Childs’ ‘Vehicle’. In ‘Grass Field’, the interior-bodily was translated to the visual and aural. Implicit in this idea of translation is the understanding that processes can be translated into each other because they share an equivalence of some kind, of means, materials, or time. We recall Hay’s description of his work’s unrelated, simultaneous processes that were, to use his description, “equal in time” (and elapsed time, as we have discussed, was the only structure that the events in a 9 Evenings work needed to have in common in an artistic and electronic environment favouring dissociation and acausality). By locating the performer’s body (Hay’s), a locus of absolute contingency, at the centre of a matrix of “equal” processes, not sidelined – as if the body were merely a source of outputs like the Armory’s control booth, which was indeed at the side of the space – Hay’s piece performed the paradox of the Judson dancers’ approach to materials. The structure of the work was one of an abstracted equivalence, but the nature of what would actually occur in performance was very much to do with the inherent qualities of the materials used.

It is also likely that the problem of scale in the Armory would have contributed to the abstraction of the dancer’s body. In the Judson Church, the space for which much of the Judson performers' works were organised, small gestures were likely to have been quite visible to the audience. Although writers have discussed the stonily matter-of-fact expressions of the Judson dancers, Rainer’s work notes, for example, reveal a good deal of choreography specifically for the face: in the ‘Bach’ section of her 1963 work Terrain, for example, Rainer’s choreography notes include an instruction to do an “arabesque with grimace” (1974: 42). Unless amplified to a great extent, say, via video projection onto a large screen, as in Alex Hay’s piece, such gestures would not be legible in a significantly larger arena like the Armory, except from the closest seats. The Judson performers may not have anticipated the results of the extreme order of amplification required.

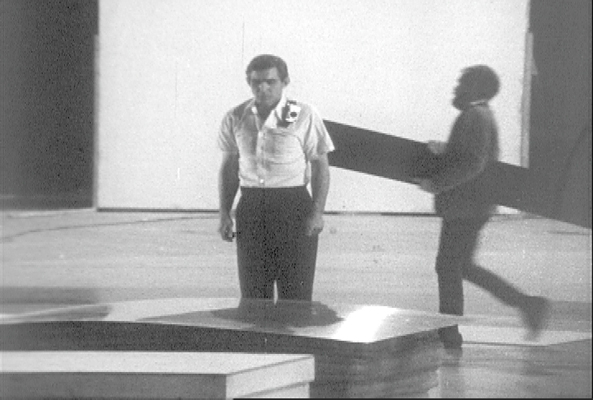

Figure 3: Frame capture, 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, ‘Carriage Discreteness,’ 1966, camera: Alfons Schilling and Bell Labs Engineers, produced by Billy Klüver, 16mm black-and-white film. Courtesy of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

Like Alex Hay’s description of ‘Grass Field’’s structure, or the juxtaposed rhythms of parallel sound and movement tracks in Deborah Hay's ‘Solo’, Rainer saw her work ‘Carriage Discreteness’ in terms of the management of separate but synced processes. Rainer described ‘Carriage Discreteness’ as “[a] dance consisting of two separate but parallel (simultaneous) continuities and two separate (but equal) control systems” (1974: 305). Rainer controlled the “performance continuity” of ‘Carriage Discreteness’ from a balcony above the Armory floor, improvising instructions to pick up and move materials which were communicated by walkie-talkie to performers (Rainer 1974: 305, Biorn 2007). Performers included the Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, who had made Styrofoam beams that were laid on the Armory floor with other objects, such as plywood, masonite, and wood planks and “slabs”. There were also four performers placed in the audience, two with bullhorns (Rainer 1974: 305). The second “parallel but simultaneous” continuity was the “event continuity”, “controlled by TEEM in its memory capacity” (Rainer 1974: 305). These events included film clips, such as W.C. Fields juggling bricks and another from a James Cagney film; slide projections; a taped conversation about a movie between Lucinda Childs and dancer William Davis; and actions involving props dropped from above or passed over the space (Rainer 1974: 305, Klüver 1979: 5). Rainer invested ‘Carriage Discreteness’ with a neutral tone and an attenuated, even temporality. Art critic Lucy Lippard, who had attended Rainer’s piece, described the performers as “aloof”, “unhurried”, evincing a “willfully antiflamboyant quality” (Lippard 1967 in C. Morris 2006: 72), much as critic Doris Hering had remarked on the “moonlike impassivity” of Deborah Hay’s piece.

Throughout her practice, Rainer had often structured performances to involve discrete movement activities within the same performance space, which Lambert analyses as investigations into spectatorial attention and distraction (2002). While we can see this strategy in ‘Carriage Discreteness’, I would like to qualify its operation. In this piece, we can also see evidence of ideas Rainer was developing concurrently, to do with the question of work, or “effort,” and how it related, or did not relate, to movement that the audience could see. Working within the same set of considerations, Rainer made her landmark work Trio A, and wrote an essay analysing it, in the same year that she made ‘Carriage Discreteness’ for 9 Evenings (although the Trio A essay would not be published until two years later, in an anthology on Minimalism). In her program notes for ‘Carriage Discreteness’, Rainer stated her interest, as she did in her Trio A essay, in making “effort” “evident or not” (1974: 305). The organisation of movement in ‘Carriage Discreteness’ – apparently unbidden from the audience perspective, as the audience could not hear Rainer's instructions – was to do with the visibility of process. Only a part of the performance activity was able to be “seen” by the spectator (not unlike the way the light bulbs in the buckets of Childs’ work were turned on and off without the audience knowing what the trigger was). Rainer was concerned with exactly what work-like activity, and the effort commensurate to it, would be shown to the spectator…or not.

The other side of Rainer's interest in what would be made visible to spectators was the issue of managing that visibility. In a passage in her 1974 book Work 1961-73 concerning the time required for the “imagery” of a piece titled Act to “register” on an audience, Rainer stated of ‘Carriage Discreteness’: “the hand of God changed the hugely dispersed configuration into a slightly different configuration” (1974: 83). Given the context of her discussion, the arrangement of performers in a space in relation to the audience’s registration of its reconfigurations over time, we can hear in Rainer’s comment an awareness, dryly humorous, of the fantasy of control – “the hand of God” – that was linked to the audience’s inability to fully perceive how the production was controlled. Rainer could be in “a place remote from the performing area” (Rainer 1974: 305), yet was nonetheless able to give instruction on the spot to performers. ‘Carriage Discreteness’, a work that could only have been actualised through the expanded scope that the 9 Evenings environment facilitated, performed both the question of the visibility of process and its coordinated management at a distance.

We have considered the effects of the intersection of Judson thinking concerning process and materials with the particular situation of 9 Evenings – the externalisation of the body's interiority through audiovisual amplification, a new uncertainty about the body’s limits as a result of its conflation with the larger performative space and a meta-management of discrete, and perhaps remote, activities. These works participated in a central mystery of this period in American industrial and cultural history, that of the relation of the tangible body to its estranged “work”. This question of the body’s labile utility and dispersion was also necessarily one of processes and systems that were fundamentally changing, the uncertainty of what would replace them, and the utter strangeness of machines whose workings could no longer be seen, nor even imagined, machines that were no longer familiarly mechanical.

I would like to thank Julie Martin for her useful clarifications and Per Biorn for his assistance with my questions on technical aspects of ‘Carriage Discreteness’.

References

Banes, S. (1993a) Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962-1964, Durham/London: Duke University Press

Banes, S. (1993b) Greenwich Village 1963: Avant-Garde Performance and the Effervescent Body, Durham/London: Duke University Press

Banes, S. (1987) Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance, Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press

Bardiot, C. (2006) “the diagrams of 9 evenings”, trans. Claire Grace, in 9 evenings reconsidered: art, theatre, and engineering, 1966, Catalogue for the exhibition 9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre, and Engineering, 1966, C. Morris, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT List Visual Arts Center

Biorn, P. (2007) Email communication with the author, February 22, 2007

Childs, L. (1966) Artist’s statement, in 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, P. Hultén and F. Königsberg (design and eds.), New York: Experiments in Art and Technology (unpaginated)

Driscoll, J. and Rogalsky M. (2001) “David Tudor’s Rainforest: An Evolving Exploration of Resonance”, The Art of David Tudor, Symposium of the Getty Research Institute

Forti, S. (1974) Handbook in Motion, Vermont: third ed. 1998, self-published, first published: Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

Fry, E. F. (1970) “Introduction”, in On the Future of Art, New York: The Viking Press, Proceedings of the 1969 lecture series On the Future of Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Goldberg, RL. (2001) Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present, London/New York: Thames & Hudson

Haskell, B. (1984) Blam! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism, and Performance 1958-1964, New York/London: Whitney Museum of American Art, in association with W.W. Norton & Company

Hay, A. (1966) Artist’s statement, in 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, P. Hultén and F. Königsberg (design and eds.), New York: Experiments in Art and Technology (unpaginated)

Hering, D. (1966) “The Engineers Had All the Fun”, Dance Magazine, vol. 40 no. 12 (December)

Hultén, K.P.G. (1968) “Foreword and Acknowledgements” in The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, Catalogue for the exhibition, New York: The Museum of Modern Art

Johnston, J. (1964) “Pain, Pleasure, Process”, Village Voice, 27 February, in Johnston, J. (1998) Marmalade Me, Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England

Jones, C. A. (1996) Machine in the Studio: Constructing the Postwar American Artist, Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press

Kahn, D. (1999) Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts, Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: The MIT Press

Klüver, B. (1979) “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering: A Description of the Artists’ Use of Sound”, manuscript, Berlin: Augen Und Ohren, Klüver-Martin Archives, Berkeley Heights, New Jersey

Klüver, B. (1967a) “Theatre and Engineering: an Experiment. 2. Notes by an engineer” in Artforum, vol. 5 no. 6 (February 1967)

Klüver, B. (1967b) “Interface: Artist/Engineer”, E.A.T. Proceedings, April 21, reprinted from a talk given at MIT, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Barbara Rose Papers, Accession No. 930100, Series III B, Box 2, folder 6

Klüver, B. (1961) “The Garden Party”, quoted in Loewen, N. (1975), Experiments in Art and Technology: A Descriptive History of the Organization, unpublished PhD dissertation, New York: Fine Arts Department, New York University

Klüver, B. and Martin J. (2003) “The Story of E.A.T.” in E.A.T. – The Story of Experiments in Art and Technology, Tokyo: NTT InterCommunication Center

Kostelanetz, R. (ed.) (1968) The Theatre of Mixed Means: An Introduction to Happenings, Kinetic Environments and Other Mixed-Means Performances, New York: Dial Press

Kuo, M. (2006) “9 evenings in reverse” in 9 evenings reconsidered: art, theatre, and engineering, 1966, Catalogue for the exhibition 9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre, and Engineering, 1966, C. Morris, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT List Visual Arts Center

Lambert, C. (2002) Yvonne Rainer’s Media: Performance and the Image, 1961-73, unpublished PhD dissertation, Stanford University

Lee, P. (2004) Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s, Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: The MIT Press

Lippard, L. (1967) “Total Theatre?” in Art International, no. 20 (January)

Loewen, N. (1975) Experiments in Art and Technology: A Descriptive History of the Organization, unpublished PhD dissertation, New York: Fine Arts Department of New York University

Martin, J. (2007a) Email communication with the author, 17 January 2007

Martin, J. (2007b) Email communication with the author, 22 February 2007

Martin, J. (2006) Email communication with the author, 27 December 2006

Mattison, R. S. (2003) Robert Rauschenberg: Breaking Boundaries, New Haven/London: Yale University Press

Meyer, J. (2001) Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties, New Haven/London: Yale University Press

Morris, C. (2006) “9 evenings: an experimental proposition (allowing for discontinuities),” in 9 evenings reconsidered: art, theatre, and engineering, 1966, Catalogue for the exhibition 9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre, and Engineering, 1966, C. Morris, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT List Visual Arts Center

Morris, R. (1970) “Some Notes on the Phenomenology of Making: The Search for the Motivated” in Artforum, vol. 8 no. 8 (April)

Munroe, A. (1994) “A Box of Smile: Tokyo Fluxus, Conceptual Art, and the School of Metaphysics,” in Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, A. Munroe, New York: Harry Abrams Incorporated

O’Doherty, B. (1966) “New York: 9 Armored Nights,” in Art and Artists, vol. 1 no. 9 (December)

Paxton, S. (1966a) Artist’s statement, in 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, P. Hultén and F. Königsberg (design and eds.), New York: Experiments in Art and Technology (unpaginated)

Paxton, S. (1966b) Page of notes headed ‘Steve Paxton’, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Experiments in Art and Technology Records 1966-1993, Accession No. 940003 reprinted as an image in Morris, C. (2006) “9 evenings: an experimental proposition (allowing for discontinuities)”

Pritchett, J. (2001) “David Tudor as Composer/Performer in Cage’s Variations II,” The Art of David Tudor, Conference Paper, Symposium of the Getty Research Institute

Rainer, Y. (1974) Work 1961-73, New York: New York University Press/Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

Rainer, Y. (1968) “A Quasi Survey of some ‘Minimalist’ Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimal Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, or an Analysis of Trio A,” in Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology, G. Battcock, New York: Dutton

Rainer, Y. and Halprin, A. (1965) “Yvonne Rainer interviews Ann Halprin” in Tulane Drama Review, vol. 10 no. 2 (Winter)

Ross, J. (2007) Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, Berkeley/London: University of California Press

Ross, J. (2003) “Anna Halprin and Improvisation as Child's Play”, in Taken by Surprise: A Dance Improvisation Reader, A. C. Albright and D. Gere eds., Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press

Rush, M. (2005) New Media in Art, London: Thames & Hudson

Sachs, S. (2003) “Chronology,” in Yvonne Rainer: Radical Juxtapositions 1961-2002, Catalogue for the exhibition: Yvonne Rainer: Radical Juxtapositions 1961-2002, Philadelphia: The University of the Arts

Shanken, E. A. (1998) “Gemini Rising, Moon in Apollo: Attitudes on the Relationship between Art and Technology in the US, 1966-71,” ISEA97: Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Electronic Art, A. Nereim ed., Chicago: ISEA97, www.duke.edu/~giftwrap/Gemini.html, accessed October 3, 2005

Teitelbaum, R. (1961) Note to the 1961 Columbia recording of Variations II, reprinted as “’Live’ Electronic Music” in Kostelanetz, R. (1970/1991) (ed.) John Cage: An Anthology, New York: Da Capo Press

Tomkins, C. (1976) The Scene: Reports on Post-Modern Art, New York: The Viking Press

Whitman, S. (1967) “Theatre and Engineering: an Experiment. 1. Notes by a participant” in Artforum, vol. 5 no. 6 (February)

Whitman, S. (1966) “Interview with Lucinda Childs 4/11/66”, typescript of interview dated April 11, 1966 between Childs and ‘S’, likely an extract from Simone Whitman’s interviews with 9 Evenings participants, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Experiments in Art and Technology Records 1966-1993, Accession No. 940003, Series I, Box 3, folder 3.15

Young, La Monte (1965) “Lecture 1960” in Tulane Drama Review, vol. 10 no. 2 (Winter)