This essay will focus on the transcoding of a work from its print form as “AFFECTions: friendship, community, bodies” (Brewster and Smith 2003) into its multimedia form as soundAFFECTs (Dean, Brewster and Hazel 2004). In particular it will explore how this transition changes the affective experience the piece transmits. The print (words only) work “AFFECTions” is an experimental and multi-genre collaboration by Anne Brewster and myself which engages with the subject of affect, feeling and emotion (Brewster and Smith 2003). The multimedia work, soundAFFECTs, employs the text of “AFFECTions” as its base, but converts it into a piece which combines text as moving image and transforming sound. For the multimedia work Roger Dean programmed a performing interface using the real-time image processing program Jitter; he also programmed a performing interface in MAX/MSP to enable algorithmic generation of the sound. This multimedia work has been shown in performance on many occasions projected on a large screen with live music; the text and sound are processed in real time and each performance is different. However linked to this article is one version of soundAFFECTs: this is a flash movie which 'captures' one rendering of the piece. It is the same version of soundAFFECTs as the web realisation of the piece referred to several times in this article (Dean, Brewster and Hazel 2004) though the web realisation is a Quicktime movie.

These transcodings of the piece are all radically different creative enactments of it, and the multimedia work – because it is processed in real-time – is itself variable each time the work is encountered. This transcoding is a form of translation but not in the sense of original and copy. As Lev Manovich says, “In new media lingo, to ‘transcode’ something is to translate it into another format” (Manovich 2001). Walter Benjamin, in his essay “The Task of the Translator” suggests that a translation is much more than the reproduction of meaning, rather it is a creative reworking of it (Benjamin 1999:70-83). For Benjamin the translator is in error “if he preserves the state in which his own language happens to be instead of allowing his language to be powerfully affected by the foreign tongue” (Benjamin 1999: 81). Tim Woods argues, very suggestively, that in Benjamin’s essay translation is seen as a kind of defamiliarisation, an “eruption of the foreign” which foregrounds the idea that “a text is never an organic, unified whole…A translation is therefore not simply a departure from the original that is either violent or faithful, since the original is already divided, exiled from itself. Not only is no text ever written in a single language, but each language is itself fractured (Woods 2002: 200-201). The idea of translation as transformative production can also be applied to the transcoding of works into different media. In such transcodings mutation is more important than fidelity to an original, and one version is not better or truer than another. Comparison between the different versions produces difference as much as similarity, and such differences are likely to already be potential in the prior text.

In the following I want to explore what happens when the verbal text “AFFECTions” transmutes into the multimedia work soundAFFECTs. In particular, I want to focus on the way in which the emotional/affective aspect of the print version changes in the multimedia transcoding as a result of technological intervention and the fusion of text, image and sound. In order to do this I will need to distinguish my use of the terms “emotion” and “affect”. I will define emotion as subjectively-based but culturally-coded categories of feeling such as happiness and anger, and affect or affective intensities as a sensation, or a flux of sensations, less tied to a particular point of view or subjectivity. My argument will be that there is a shift in the multimedia work so that it communicates much more strongly through affective intensities, than the print text, and much less through the depiction and communication of subjectively-based emotional states. However the potential for this shift is inherent in the print text which oscillates between emotion and affect as I define it here, and is therefore already marked by difference “divided, exiled from itself” (Woods 2002: 201). An important part of my discussion will be exploring theoretical frameworks from cultural theory and cognitive psychology – discourses which were themselves influential in the writing of the piece – as a means to consider the change in emotional /affective experience which takes place in the transcoding from print to multimedia.

The print text: emotion and affect

In contemporary literary studies there has been a problem with regard to the discourse about emotion of which critics are becoming increasingly aware. In the 70s or 80s, literary studies – appropriately and very importantly – problematised the humanist assumptions underlying notions of writing as self-expression, and foregrounded the mediating activity of language. But as a consequence it somewhat bracketed out emotion/affect. For literary studies to reincorporate emotion it needs to distinguish, as Rei Terada does, between emotion and self-expression. In order to do this Terada argues, somewhat confusingly, that emotion is nonsubjective (Terada 2001). It is also necessary to discuss emotion in literature beyond narrowly equating it with certain kinds of realist or lyric writing in which codifiable emotions are readily recognisable, and which communicate through realist strategies of emotional involvement and identification. In some forms of experimental poetry, for example, in which realist representation and a cohesive subjectivity is problematised, emotion is less subjectively-based and is at least partly broken down into affective intensities. In the following I want to show how “AFFECTions”, the print-based collaboration from which the multimedia work was made, oscillates between emotion and affect, so that the affective intensities accentuated in the transcoded/translated multimedia work are already partly present within it. In order to do this I need to retrospectively talk about the writing of “AFFECTions” and its theoretical bases.

“AFFECTions” is a fictocritical, mixed-genre work: fictocriticism is a form of writing which brings creative and theoretical writing into a resonant relationship with each other and creates symbiosis and friction between the two (Brewster 1996; Kerr and Nettelbeck 1998). The piece is therefore a mixture of fiction, poetry, theoretical exposition and quotation. It consists of about thirty short sections, or modules, with varying degrees of disjuncture and conjuncture between sections. “AFFECTions” is a constellation of short narratives, poems, and sections of theory, but there are no through narratives, consistent metaphors or overriding arguments. Rather the piece explores affect from a number of different perspectives without trying to resolve them. The critical and creative work are juxtaposed, but one does not explain or illustrate the other, rather they exist in a reflexive, porous and open relationship. The piece does not take a position on affect, but circles round the topic in ways which bring together diverse, even conflicting, perspectives. It includes interjections about affect in relation to the process of writing, performance, the media, the war in Iraq, cyberspace, music, dance, ethics, representation, and so on.

In order to create the piece we read widely within the literature about affect and emotion – though not systematically or comprehensively. In other words our reading was exploratory, and we read to trigger creative responses, rather than to produce an overarching intellectual argument. Our reading was drawn from a number of different fields including literary and cultural theory, philosophy and cognitive psychology, but in retrospect two theoretical perspectives seem to hover over the piece. These two perspectives are, broadly speaking, from cognitive psychology and cultural studies. They also form the basis of my analysis, though this includes material I have read since we wrote the piece as well as before, and I will not attempt to distinguish between the various stages of that reading. Whereas the initial reading by both of us provided a trigger for the creation of the piece and the ideas in it, further perusal of the relevant theory has helped me to ponder retrospectively how the piece both talks about affect and encodes its own affective experiences. It has enabled me to conceptualise how this emotional/affective experience is transmuted when the piece is transcoded or “translated” from print to multimedia.

The first of these perspectives stems from the work of cognitive psychologist Keith Oatley, and is largely geared to emotion as I have defined it above. Oatley argues that emotions are cognitive responses, accompanied by bodily sensations, to our tendency to make plans and goals. Drawing on his work with Johnson-Laird, Oatley proposes that “an emotion occurs in relation to a person’s several plans and goals when there is a significant change in assessment of the outcome of a goal or plan” (Oatley 1992: 46). The matter is complex, however, because we have multiple goals which are in conflict with each other, and emotions enable us to coordinate these goals. We experience positive emotions when this coordination is successful, negative emotions when it fails (1992: 46). For Oatley:

emotions derive from the cognitive processes for integrating multiple and sometimes vague goals and for managing plans that are enacted with limited resources in an uncertain environment, often in conjunction with other people. Happy emotions occur when coordination between plans is being achieved and unanticipated events are assimilated. Distressing emotions occur when coordination fails, or when some plan goes badly, when a problem emerges that cannot be solved from current resources or when an important background goal is violated. Emotions function to allow otherwise disparate aspects of a complex system to be co-ordinated (1992: 43-44).

According to Oatley, therefore, emotions serve useful functions in helping us integrate our goals and plans, and can be important for quick decision-making because we do not have to sift through all the arguments or possibilities in the way which might be necessary to make that decision by purely logical means. Oatley questions the idea that emotions are necessarily irrational while thought is rational – even if that is true in some cases – and views emotions as an aid to thinking and behaving.Emotions can be an aid to making decisions rapidly in cases where there is incomplete information:

What they do is prompt us in a way that on average, during the course of evolution and assisted by our own development, has been better either than simply acting randomly or than becoming lost in thought trying to calculate the best possible action (Oatley and Jenkins 1996: 258).

This, according to Oatley (and Jenkins), is an example of heuristics; a heuristic is “a method of doing something that is usually useful when there is no guaranteed solution” (1996: 258). Oatley is unusual in the way he draws many of his examples from literary texts, blurring the distinction between real life and fictional cases. But these are usually realist 19th century texts such as Anna Karenina or Middlemarch, in which the emphasis is upon character and situation. Oatley tends to analyse situations within the novels in terms of the emotions the characters experience, and how these relate to the frustration or fulfillment of their plans. He does not attempt to look at affect in less realist fiction or poetry, and he also does not consider the psychology of the reader and how this might be involved in the means by which the work communicates. In particular, he does not attempt to investigate how the reading process itself might be characterised by emotional interruption or fulfillment.

On the other hand, our reading also encompassed cultural studies material which was influenced by the work of Deleuze and Guattari. This material tends to interrogate the assumptions behind more humanist perspectives, and consequently is less cognitively and subject/person-based. Rather it stresses pre-personal and non-subjective “intensities”. For Deleuze and Guattari everything belongs to a flow of “becoming” which constitutes one immanent plane of being. According to them we have to perceptually and intellectually carve up the world to understand it, but fundamentally everything is interconnected. Deleuze and Guattari do not deny the presence of the subject, but see the subject as an artificial construction. For Deleuze and Guattari (1994) emotions and perceptions become affects and percepts at least partially detached from a point of view centred in a specific subject. Here the distinction between subject and object central to cognitive theory collapses, as affects cross over, engage with, and move between both human and non-human bodies producing affective intensities. Deleuze and Guattari also draw attention to different formations of sensations such as “the embrace” or “the clinch” (the coupling of sensations) and “withdrawal, division and distension” (the uncoupling of sensations) (1994: 168). Affect is closely linked in Deleuze and Guattari’s work with transformation and even with creativity itself. They suggest that artists are “presenters of affects, the inventors and creators of affect” (1994: 168) and that “a great novelist is above all an artist who invents unknown or unrecognized affects and brings them to light as the becoming of his characters” (1994: 174).

We also explored cultural studies material, particularly the work of Brian Massumi, which focuses on the relationship between affect and politics: the way in which responses to political events can be primarily affective, and the means by which affect is manipulated through the media by politicians to draw the populace into line with a conservative view of current events (Massumi 2002).

Both these perspectives (the cognitive and the cultural) are incorporated into the collaboration in direct and subliminal ways. In some sections the theoretical input is quite direct, such as in the following passage which outlines Keith Oatley’s ideas and then moves outward with the idea of the plot – the fictional equivalent of Oatley’s “real-life” plan:

Keith Oatley argues that emotions are cognitive processes that arise from our tendency as human agents to make plans, rather like plots in a narrative. Positive emotions occur when goals are fulfilled, negative ones when they are thwarted. The situation is complex, because we usually have multiple conflicting goals; our plans involve other people; and we often have to make decisions in an unpredictable environment. Not just one plot, then, but plots within plots, competing plots, and plots without beginning or end.

(Brewster and Smith 2003)

Another passage also draws on theoretical material from Derrida, and implicitly Massumi. It introduces the notion of the manipulation of feeling by politicians at the start of the Iraq war, partly through the promotion of stereotypical and negatively geared emotions towards the “enemy”. The affective reaction of the speaker is one of bodily dysfunction:

It's 11.30 p.m., just before Bush is to address the US. I am almost incapacitated by a tired sick feeling. I guess we have all become drugged by the American imperative to feel — outrage, fear, pride (and our intense counter-feeling which John Howard named this morning in his address to the nation as 'rancour') which started with the attacks of September 11th. We watched with a growing frustration the incitement in the US of a powerful discourse of feelings, an instrumentalist military sublime. The American president drew a justification for war-mongering on the basis of his feelings of outrage. He once again arrogates to the American people the right to be human, to suffer; correspondingly the inhuman is returned to the third world, which has no claim to a collective subjectivity.

A journalist asked John Howard this morning whether he saw historical precedents (such as Viet Nam) in the current situation and he blithely dismissed 'history'. At times like this, he said, we can only think about the present. This is precisely where a discourse of feelings is so politically expeditious; it erases the history of antagonisms and an analysis of causes (such as a rapacious US foreign policy). And so we see the insidious effects of instrumentalist feeling in what Derrida calls the grotesque 'onto-theology of national humanism'.

(Brewster and Smith 2003)

Different approaches to emotion and affect hover over the piece thematically, but formal aspects of the piece can also be construed in a similar light. On the one hand there is more subject-based writing, that is writing where we are aware of authors, characters, narrators or voices as focal points, even though they are highly constructed and tend to convey emotions which are conflicting, complex and destabilising. These passages tend more towards the depiction of emotional situations and the pressure toward emotional identification by the reader. On the other hand, the piece also includes types of writing which are less subject-based and which convey affect in a way less tied to a particular point of view or focalisation. These passages move closer to the notion of affective intensities. Obviously these two extremes (the more subject-based and the less subject-based) form the end points of a continuum and most of the writing is along that continuum rather than at its extremes.

Similarly, the collaboration involves different ways of engaging with affect and emotion through linguistic and generic strategies aimed at representation or the break down of representation. On the one hand, it consists of more (though by no means entirely) narrative, realist and expositional types of writing, which at least partially encourage the illusion of emotional identification by the reader with situations and characters within the text – as well as some passages which directly transmit theoretical ideas. But at the same time it also includes types of writing which break up semantic, narrative or descriptive continuities. These types of writing tend to disrupt emotional categories and dissolve them into a flow, or assemblage, of sensations/impressions or affective intensities. Such writing has a strong connection with the long tradition of twentieth and twenty-first century experimental writing and, most recently, with American language writing and its various successors.

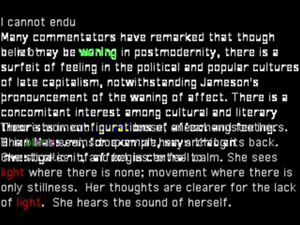

Two examples will serve to illustrate the way the different modes of writing are inscribed in the text (UNSW stands here for University of New South Wales):

|

|

|

|

In the first poem the sense of subjectivity is fragile. The speaker wonders if she can still be alive if she is not remembered, and expresses considerable doubts about what her feelings actually are: whether they are joy at “escaping”, or regret at no longer being in the former workplace. Feelings are not characterised as being easily coordinated cognitively: “I don’t recognise a feeling until I’m falling out of it”. However, despite the fragility of the subject, and her lack of emotional and cognitive coordination, there is a sense of a focal subjectivity and an identifiable situation – the removal from one work environment to another. In Keith Oatley’s terms, the emotional ambivalence is caused by the conflict between two goals: the desire for change and a new workplace, and nostalgia for the previous one.

In the second piece, however, an overall point of view, or single identifiable situation, is less present. This is hardly surprising because the piece is a collage composed of fragments taken from newspaper headlines during the (second) 2003 Iraq invasion by the US-led coalition. In this piece there is less sense that the fragments project a unified point of view. The indecisiveness or hesitancy at the end is not that of a particular person, and while the fragments suggest a situation — for example “shock and awe” was the name given to the attacks in the Iraq war — that situation is conveyed in a way which is indeterminate and fractured. It does not relate the sensations it transmits – such as “stunned” – to a particular consciousness, or locate them in a personalised emotional state. Furthermore, different viewpoints – such as that of the propagandist government and of the reader of the newspaper – are collapsed into each other, so that an overiding viewpoint is splintered and multiple perspectives unfold which include feelings of disarray and impotence. These are not firmly rooted in a consistent subjectivity and as a result seem close to the concept of affective intensities. Another section of the collaboration, “Frrrustration” is also a very good example of affective intensities because it is composed almost entirely of bodily sensations conveyed in a build up of short phrases: “the body takes over like a crazed mechanical wind-up toy, rehearsing the pretext of metaphor. its elegiac pulse thumping like a jackhammer, its discursive fluids leaking, bones grinding, muscles clenched in this Olympian task of speaking”.

Overall, then, the print text oscillates between emotional identification and affective intensities, taking up also various positions in between, and transmitting ideas about emotion and affect through both its content and its form.

From print to multimedia and from emotion to affect.

I now want to explore how in the transcoding from print to multimedia the piece shifts more strongly from emotional identification to affective intensities. The multimedia piece is called soundAFFECTs and it brings together text, image and sound. soundAFFECTs uses “AFFECTions” as its base though it does not employ the whole text. Sections of the text now take the form of modules, each created as still or moving frames of a digital video, which are rearranged in each digital version. The modules are processed by Roger Dean, with programs written by him within the real-time image-processing platform Jitter, treating the text as a series of visual objects. The most important difference between soundAFFECTs, the multimedia work, and “Affections”, the page-based text, is variability. In the multimedia work there is no fixed text; the order of texts, and the way any particular one is processed, will be reconstituted each time. In other words, the multimedia work consists of an infinite number of realisations which nevertheless have some common features. The soundtrack, or at least a significant portion of it, is generated by Roger from the same algorithms and is also variable. This means there will always be some shared features between the versions but also considerable differences. So this is a form of creative production which is dynamic, productive and generative, unlike the print text which remains identical with itself on a material level even if it is composed of differences at the level of content and style.

A number of different processes occur in soundAFFECTs. The texts are treated as visual objects in blocks. They are superimposed on each other; they are also stretched or compressed. Texts disintegrate into, and overwrite, other texts (though they do not necessarily overwrite them in the sense of replacing them). Texts are repeated, the screen divides into several sections sometimes multiplying the same text, sometimes combining different ones, and so on. At times – particularly towards the latter end of the processing – the text becomes an intensively visual, dynamic and kinetic spectacle, with the screen divided into several segments and a number of different processes operating at once with considerable rapidity. soundAFFECTs greatly accentuates certain characteristics already inherent in the print text towards interruption, fragmentation, circularity and non-linearity. It also speeds everything up enormously, creating a sense of extreme flux. The processing and the speed problematise the reading process: the words are “flickering signifiers” (Hayles 1999: 47- 48). Sometimes they disappear before they can be fully digested, sometimes they appear in only partly readable forms, or even in forms which can hardly be read at all. soundAFFECTs speeds reading up (we cannot read at our own pace and must scan the text much of the time rather than reading it); it also promotes movement and transformation of the text.

Most relevantly to my argument, the multimedia realisation(s) break down the semantic, narrative and expositional aspects of the print realisation. In so doing they largely erode a sense of the subject (distinct authors, narrators, characters or voices). The words point momentarily to authors or narrators who themselves flicker, transform and dissolve. Relevant here is Katherine Hayles’s idea that the binary opposition between presence and absence (so predominant in some poststructuralist thinking) has been replaced in the discourses of informational systems by the binary of pattern and randomness. But Hayles also argues that the need to theorise embodiment as part of the cyber-experience means that pattern must go hand in hand with presence, randomness with absence (Hayles 1999). In soundAFFECTs words become patterns not only because they transform into visual designs, but also because they convey shifting patterns of meaning which are not continuous or sustained. At the same time the ghostly sense of voices/bodies which put these patterns into motion, or arise out of them, continuously haunts the text. These voices /bodies are those of the authors who are writing the text, the narrators who transmit it, and the characters who inhabit it.

This leads us to the multi-sensory aspect of soundAFFECTs: text, image and word combine and this greatly increases the range and interaction of sensations. An important aspect of this is what I have elsewhere called semiotic exchange, that is the way different media, when brought together, can modify – even take on – each other’s characteristics (Smith and Dean 1997). In soundAFFECTs the text becomes image, while the sound intensifies the content of the words. This is a type of synaesthesia – that is, one sensory modality is “translated” into another so that the meaning of the words is experienced in terms of both sonic and visual stimuli (in poetry synaesthesia usually alludes to the transference which occurs in metaphor from one sensory realm to another). Synaesthesia is central to multimedia practice, but in soundAFFECTs it also takes the form of what we have conceptualised as “algorithmic synaesthesia” (Dean, Whitelaw, Smith and Worrall 2006). In algorithmic synaesthesia image and sound share, at least partly, the same data and algorithmic processes. In soundAFFECTs, for example, many of the sonic effects are “translations” of the movements of the text as image, and in the web version of the piece it is noticeable that the greatest density of sound is where there is most movement in the image. In addition, some of the source sounds which may be implemented in renderings of the piece were made using programs such as Metasynth, in which a static image is read kinetically by an algorithm which generates sound. (Some of the technical details of the programming and performance of the image and sound were provided for me by Roger Dean).

The sound, in particular, is extremely important in the shift from emotion to affect because sound (in general) is a flux of sensations, even more than words. Words, in contrast, always bear the burden of a referentiality which partly interrupts and fixes the flux, and point to concrete situations in which pure sensation is dampened down, objectified and solidified. Discussion of emotion in music, for example in the work of Meyer, has often centred on the way it evokes emotional states deriving from the fulfilment or frustration of expectations (see Meyer 1956). This is somewhat akin to Oatley’s concept that emotions arise in response to the fulfilment or interruption of goals. However the concept of a flux of sensations – of affective intensities – seems to address more directly music’s abstract, less cognitive and less referential aspects. This is particularly significant with regard to computer music, where audience expectations are likely to be less pronounced than in more traditional musical forms.

In soundAFFECTs the sound continually moves the words beyond the domain of the referential while also interacting with it. Lawrence Kramer’s work on mixed media and musical meaning is relevant here (Kramer 2002). He argues that music is more “semantically absorptive” than other media. When juxtaposed with the “imagetext” – a term he has adopted from W.J.T. Mitchell to signify the fusion of image and text – music takes on the semantic meanings generated by that imagetext. At the same time musical meaning exceeds the referentiality of the imagetext. In mixed-media, Kramer suggests, meaning “runs on a loop” (2002: 153). The music seems to emit a meaning that “it actually returns, and what it returns, it enriches and transforms” ( 2002: 153). For Kramer:

From the standpoint of the imagetext, music has greater communicative immediacy, though less communicative power. Music, indeed, is one of the defining modes of an immediacy that the imagetext has to exclude in order to stabilise itself, to enable its generalising, abstracting, and speculative capacities, even at the cost of an ambivalent fascination with the excluded and excluding other. But as soon as meaning effectively runs from the imagetext to music along the semantic loop, the music seems to convey that meaning to and through the imagetext in preconceptual, prerepresentational form (Kramer 2002: 153).

While Kramer does not refer specifically to affect here, the affective properties of music – and I mean affect here rather than emotion – seem to be implied in this idea of the capacity of music to return meaning to the imagetext in “preconceptual, prerepresentational form”.

The sound in soundAFFECTs is algorithmically generated and different in each performance. Nevertheless, all renderings of it will involve the genre known as noise: this means that the sound changes, but the changes come from relative distribution of energy in the frequencies, rather than abrupt transitions of pitches and “notes”. There is, therefore, a continuous flow of sound with some variation, but it is not structured in a way which segments it or emphasises beginning, middle and end. It is rather like Deleuze and Guattari’s description of a plateau as “a continuous, self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination point or external end” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 22). In several sequences in the web actualisation, for example, the sound consists of a band of frequencies which move from low to high in a repeating cycle. The impression when listening to the opening of this realisation of the piece is of protracted ascents of rising pitches. These slow ascents then develop into simultaneous ascending cycles at different speeds but with increasing density and leveling out of the pitch as the piece progresses. In addition, the use of multi-channel, spatialised sound when the work is performed live produces a high degree of immersion for the audience which helps them to receive the work with immediacy and as a flux of sensations. This immersion is greatly accentuated by the darkened room, the large screen, and the sharing of the experience with others. In this respect the experience of the web realisation is different from that of the performance realisation(s).

All these factors result in a much stronger push and pull between continuity and discontinuity in the multimedia work than in the print text. On the one hand, the texts are more interruptive in the multimedia work and rapidly displace each other; there are also interruptions when from time to time a black screen lingers between texts. But in other respects the multimedia work is much more continuous: there are no gaps between the texts, except for the occasional black spaces; there is considerable repetition of texts and the disparate texts are welded together with image and sound. The overall effect is that the multimedia realisation(s) break up the emotional ups and downs and emotional identifications which characterise some sections of the print text into a flux of sensations. As a result they produce an affective environment which fluctuates more continuously than the “words only” text.

The question remains, then, how we can theorise this change in affective experience in the transcoding from print to multimedia. I suggest that in order to do this we look at it through the lens of the cultural and cognitive theory, I discussed earlier. In terms of Deleuzian theory, the multimedia work is stronger, as I have already implied, at creating “affective intensities”. Sensations couple and uncouple in the way Deleuze and Guattari describe, as the texts are superimposed on each other or disintegrate, and the words couple and uncouple with image and sound. The multimedia work soundAFFECTs increases, much more than the print work, “Affections”, the flow of becoming (that is, it speeds everything up). Deleuze talks about how we slow down the flow of becoming, the vast and chaotic data we receive, in order to perceive and comprehend the world. Speeding it up again is perhaps to return, even if momentarily, to the state of flux and becoming. soundAFFECTs also puts what Deleuze and Guattari call “planes of composition” together (in this case the sequences in Jitter) only to disrupt them, making a non-linear text considerably less linear. Here non-linearity seems to be identified with increased intensity. Massumi suggests that “intensity would seem to be associated with nonlinear processes: it creates resonation and feedback that momentarily suspend the linear progress of the narrative present from past to future” (Massumi 2002: 26).

In addition, soundAFFECTs detaches emotions and perceptions from a sustained monolithic point of view, creating affects and percepts. This happens because the multimedia piece breaks down – much further than the print text – the sense of specific states of affect and perception rooted in particular subjects, though the process is already beginning in the print text. These affects and precepts are not distinct states, linked together by causes and effects, but are multiple, simultaneous and superimposed. So soundAFFECTs puts the focus – even more than “Affections” – on the relationality between texts, and the relation between text, image and sound. The ascending and overlapping cycles of sound, described above, also communicate a sense of changing and simultaneous intensities, rather than evoking a particular emotional state.

In fact soundAFFECTs produces its ethical and political content through affective intensities rather than sustained representation or exposition of political issues. The screener/reader catches glimpses of political and ethical meanings rather than detailed political insights, and these meanings are extended, fractured and transmogrified by the addition of the sound and the transmutation of text into image. This is, of course, in keeping with objectives of avant-garde art which has always conveyed political meanings in ways which are fragmented, anti-representational and intermedia. Relevant here is the work of Tim Woods and Andrew Gibson who theorise outwards from the theoretical stance of Emmanuel Levinas to argue that an ethical writing does not have to be determinate or representational. This is because ethics itself is not built on a foundational or fixed morality: for Gibson it is not based on “categories, principles or codes” and does not presume “an exteriority comprehensible in terms of hypostasised essences, static identities or wholes” (Gibson 1999: 16). For Woods, similarly, an ethical poetry does not involve totalities and totalising structures, but emerges in fragments, gaps and fissures typical of an alternative tradition of poetic writing from Gertrude Stein to American Language Poetry. An ethical poetry, according to Woods, resides in a “poetics of interruption” (Woods 2002: 255). This poetics of interruption is also a vehicle for affect: in soundAFFECTs, the political and ethical become affective through the increased intensity brought by the visual and sonic, despite the gaps in the meaning.

On the other hand, the work of Keith Oatley, with some qualifications, can also shed light on this transition from print to multimedia. To adopt Oatley’s theoretical stance is to view the work from a more cognitive and empirically based position, and any extrapolation we make from his ideas could only be tested in an experimental/empirical context. In order to do this we have to adapt Oatley’s ideas to the reading/reception process which he does not himself do. In so doing, we can speculate that the experience of viewing soundAFFECTs is that of forming a plan made up of sub-plans which need to be coordinated. Throughout the work we can hypothesise that there is a push and pull for the reader/screener between the fulfillment of the overall plan (the absorption of the multi-sensory work) and the interruption of the plan by the sub plans (the reading of the texts). This interruption gives rise to a state of rapidly fluctuating arousal.

The main problem with Oatley’s approach, from a cultural theory perspective, is that it retreats into more subject-based, humanist position and that it falls back into the idea of emotion. However, Oatley’s theoretical framework has the advantage of being very concrete and precise. It could be used as the basis of empirical research to explore matters of reception, and how reactions of the audience differ when reading the text, viewing the multimedia work, or experiencing a combination of the two.

To conclude, the transcoding of the text “AFFECTions: friendship, community, bodies” into the multimedia experience of soundAFFECTs provides a changed affective experience characterised by a rapid flux of sensations rather than sustained emotional build-ups and identifications. To account for this transition, and the impact of the multimedia work, we require a theoretical framework which engages with the idea of affective intensities put forward by Deleuze and Guattari. But it is also useful to take on board Oatley’s concept of emotional interruption and its possible applications. Ideally, an appreciation of the piece would involve reading “AFFECTions” and viewing soundAFFECTs, since both works evoke different types of meaning and affective response which can be seen to be mutually enriching; here transcoding becomes a two-way, symbiotic process. Reading texts, listening to sound, or looking at images is increasingly part of a multimodal experience which requires negotiation between different media, technological environments, and affective experiences. Such a multimodality points to a huge diversity of textual possibilities, an increased range of aesthetic and cultural modes of production, and to transcoding as an ongoing and continuously evolving process.

References

Benjamin, W. (1999) Illuminations, London: Pimlico

Brewster, A. (1996) “Fictocriticism: Undisciplined Writing”, Proceedings of the first Conference of the Association of University Writing Programs, Sydney, University of Technology, Sydney

Brewster, A. and H. Smith (2003) “AFFECTions: friendship, community bodies”, in Text. vol. 7 no. 2, http://www.gu.edu.au/school/art/text/oct03/brewstersmith.htm, accessed February 20, 2007

Dean, R., A. Brewster and S. Hazel (2004) “soundAFFECTs”, in Text. vol. 8 no. 2, http://www.griffith.edu.au/school/art/text/oct04/content.htm, or http://www.gu.edu.au/school/art/text/oct04/smith2.mov, accessed February 20, 2007

Dean, R., M. Whitelaw, H. Smith and D. Worrall (2006) “The Mirage of Real-Time Algorithmic Synaesthesia: Some Compositional Mechanisms and Research Agendas in Computer Music and Sonification” in Contemporary Music Review, vol. 25 no. 4, pp. 311-326

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1994) “Percept, Affect, and Concept” in What is Philosophy, London/New York: Verso

Deleuze, G. and Guattari F. (1994) What is Philosophy? London/New York: Verso

Gibson, A. (1999) Postmodernity, Ethics and the Novel: from Leavis to Levinas, London/New York: Routledge

Hayles, N. K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Kerr, H. and Nettelbeck A. (eds.) (1998) The Space Between: Australian Women Writing Fictocriticism, Perth: University of Western Australia Press

Kramer, L. (2002) Musical Meaning: Toward a Critical History, Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press

Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press

Massumi, B. (2002) Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Durham/ London: Duke University Press

Meyer, L. B. (1956) Emotion and Meaning in Music, Chicago

Oatley, K. (1992) Best Laid Schemes: The Psychology of Emotions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Oatley, K. and J. M. Jenkins (1996) Understanding Emotions, Oxford: Blackwell

Smith, H. and R. T. Dean (1997) Improvisation, Hypermedia and the Arts since 1945, London: Harwood Academic

Terada, R. (2001) Feeling in Theory: Emotion after the “Death of the Subject”, Cambridge, Mass./London: Harvard University Press

Woods, T. (2002) The Poetics of the Limit: Ethics and Politics in Modern and Contemporary American Poetry, Basingstoke: Palgrave