With the proliferation and increased accessibility of online news aggregators, RSS news subscription-like feeds, online versions of newspapers, and information news databases, comes new possibilities for news analysis. In this paper we propose the use of new software tools and methods of analysis to determine the manner in which political leaders and social issues were covered in online news stories during the Canadian federal election (December 2005 to January 2006). In so doing we point out the biases of online news aggregators such as Google News, specifically the degree to which large commercial news outlets dominate such Internet news sites. That said, we recognise that our case studies, investigating the initial reaction of online news stories to televised leaders debates, clearly benefited from the near real-time uploading of stories minutes after the conclusion of the debates.

News research has of course always stressed the importance of time, either the timeliness of news, the news cycle, or the history of news (Patelis 2000, Schudson 2003, Tuchman, 1978). News stories are now uploaded onto websites, sometimes within minutes after the story has been written or edited. The collapse of time between writing and publishing/disseminating of news stories thus raises questions about how such online news aggregators (for example Google news, the main focus of this paper) while claiming to democratise news voices and perspectives through the internet, might in fact be entrenching the power of news wires and large commercial news outlets that have dominated the public sphere for the last century. As Cooper (2003: 26) argues,

“While the Internet has opened possibilities for new avenues of civic discourse, it has not yet even begun to dislodge commercial media from their overwhelmingly dominant role. There is also a strong trend of commercialisation and centralisation of control over the Internet that may restrict its ultimate impact on civic discourse.”

The concern with timeliness of news uploads, and their subsequent posting on sites such as Google news, again highlights media and news researchers historical concerns about how 'breaking news' stories frame or set the agenda for both subsequent reportage and news consumers (Bruns 2005, Entman 1993, Gamson 1989, Tuchman 1978, White 1964). The formatting of news into online portals or searchable databases also presents serious challenges to news and media researchers. While we suspect media researchers will not yearn for the days of nausea inducing micro fiche or film reading machines, the possibilities for cloudy thinking and dizzy heads still very much exists. Online news researchers can be very easily overwhelmed by the scope of digital news repositories, Google news searches for example can return tens of thousand of news stories, the information database Factiva returns thousands of hits. Studies that use specific online newspapers are much less problematic, with fewer large-scale methodological and technological questions (Menashe 1998, Saguy & Riley 2005).

This paper though is primarily concerned with applying new online research tools and methods to study of online news, in particular as formatted by the information powerhouse Google. With the widespread use of digital databases and online search engines come the persistent problem of search queries and parameters. Online news research requires a deft deployment of keywords to produce data sets of online news stories. A researcher therefore must already be relatively knowledgeable in his or her area of study as only a slight change in keyword search language can produce wildly differing types of news stories. Consequently in this paper we look to disaggregate or parse the various keyword tags, date stamps and other digital codes embedded in news stories that Google, Yahoo, Altavista and others use to rank and retrieve online news stories, as well as consider some of the larger contextual factors that structure query returns. In so doing we seek to delineate the possibilities and pitfalls of conducting digital news research.

We focus many of our comments on the Google news portal, and not newer technologies such as RSS feeds, for a number of reasons. First, information and news aggregators such as Google serve a distinct 'mass mediated' or aggregation function – as a one stop information shopping portal they promise to pull together, through de-centered and distributed algorithms, the most relevant news stories of the day. Second, Google, Yahoo and others format and rank their news stories both for their aggregated news portals and their RSS feeds. Thus, as Glaser (2005) argues, "While you can put your [RSS] feeds into news sections, you still can't pre-empt the top news story of the day." Additionally, users are 'prompted' with a pre-selected list of RSS feeds in order to lower the tech-savvy threshold and increase the spread of RSS. Therefore, in both cases there is a need to understand and investigate possible ranking and prompting biases as aggregators make RSS more widely available. Lastly, as Rogers and Ben-David detail, Google's search engine offers a controversial definition of news. In theory, press-releases (from governmental bodies or otherwise), mainstream news stories, and alternative press news stories all commingle in the data aggregate provided by Google as "news". In reality, through the process of ranking stories (for example by giving some stories added prominence through position and size of font, inclusion of photographs etc.) as we will see later, in the study of news coverage of the recent Canadian federal election, Google consistently promotes official, authoritative, commercial news sources and stories. Thus advances in access, quantity of news stories, and news "freshness", must be balanced against Google’s introduction, into their proprietary ranking algorithm, of factors such as the news outlet's staff size and reputation which are automated along with average story length and the like. These factors, in combination, have led to the observation that Google News is at risk of becoming more reflective of mainstream and commercial media, a phenomenon witnessed more broadly on the Web as well since the turn of the millennium. (For a discussion of Google News and literature relating to aggregator behaviour see Rogers and Ben-David 2005; for a discussion of side-by-sidedness see Rogers 2004).

Our investigation of potential online news biases and coverage focused on the coverage surrounding the Canadian federal election campaign in December 2005 and January 2006. Two media events were investigated, first the obviously staged, but widely reported leaders debates (The format of the leaders debates was hotly contested in Canada as the previous debates, two years earlier had been widely seen as too confrontational with leaders speaking over one another and consistently out of turn. As a result a more controlled format was introduced and these changes became a significant topic of discussion and media coverage during the period covered by our research: see Figure 2) and second, the media reaction to the shooting of a teenage girl during the busy boxing day shopping and holiday period in downtown Toronto – one in a series of violent shootings that rocked Canada's largest city over 2005. Subsequently media and citizens groups seized upon the shooting making it a significant campaign issue coming as it did roughly in the middle of the six week election campaign.

For the first debate research we deployed the search query “[federal party leader name] + Canada + Debate”, for the shooting example we used the search terms "Gun Violence + [federal party leader name]". These Google news queries were applied to all of the main federal party leaders in Canada (ie. “Stephen Harper + Canada + Debate” and “Stephen Harper + Gun Violence”) and then launched. To put the news returns into a more flexible database format the web tool called the "news scraper" was used. The scraper was produced by the Govcom.org Foundation, Amsterdam, and is part of an experimental suite that allows researchers to launch multiple queries into Google News or examine images and blog coverage online (http://tools.issuecrawler.net/). The scraper returns all of the relevant stories as a comma separated file including the search terms/query, URL of the story, date that it was posted, news outlet, location (country of origin), headline, and lead paragraph (or 'teaser text'). These data sets were then converted into a graphic representation by the heterogeneous data visualisation program Reseau-Lu (www.aguidel.com). The software makes visible the relationships between variables in a data set. We visualise two comparative sets of analysis herein. The first visualisation (Figure 1) cross-references a respective party leader (the initial query terms) with their coverage in multiple news outlets. In other words, the first map visualises which news outlets covered which respective leader or leaders. The second news map (Figure 2) cross-references respective party leader(s) (the initial query terms) with the story headlines from news sources. The news stories visualised in the Figures 1 & 2, the election debate maps, were gathered from Google news one hour after the end of the nationally televised leaders debate. The gun violence news stories (presented in Figure 3) were gathered three days after Boxing Day, 2006, when the shooting occurred.

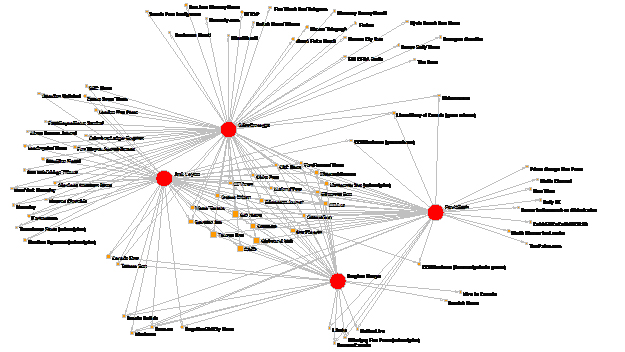

Figure 1 : First English Language Debate, Leader x News Source, Dec. 17, 2005 (click image for full size version)

Unlike Google's formatted news site, which ranks stories and presents them accordingly on their news portal (giving some stories and news outlets clear prominence over others), our visualisation uses the subject of the news stories, the party leader(s), to anchor the coverage (represented as red dots on the map). As a consequence, in the map above the visualisation provides much more than ranking of relevance – it takes the metadata embedded in the code of the news story to, in this example, visualise which party leader was mentioned by which news outlet. Looking at the map, it's abundantly clear, although not terribly surprising, to find that the commercial media dominate the coverage of the debate (we restricted our analysis to the top 25 news stories provided by Google News, future research might answer the question as to how 'far down' the ranking – if at all – alternative, not-for-profit, or smaller media outlet stories might be found). This finding would confirm our fear about certain forms of media outlets (and wire services) being able to produce stories in such a short time frame after an event. As an analysis of how media treat the party leaders, the news map, however, offers some compelling findings. What we view as Google's more controversial "news" items (press releases for example) were much more aligned with the incumbent Liberal Prime Minister, Paul Martin. A Liberal party of Canada press release discusses Martin, Layton (leader of the social democratic, New Democratic Party) and Gilles Duceppe (leader of the separatist Bloc Quebecois) in this manner, while a CCNMathews press release discusses only Martin and Layton. The fact that the leader of the Liberal party was most closely associated with the news releases is quite telling - in the lead up to the election the governing Liberal party was broadly critiqued as a tired and entrenched political machine flush with dubious insiders and questionable associates.

Interestingly, stories from International news outlets focused mostly on the smallest opposition party's leaders Layton and Duceppe. However, many of these stories are AP or newswire stories, particularly from U.S. outlets. This phenomenon is most pronounced in the coverage of Duceppe, while the international (mainly UK) sources covering Layton seem to produce more original material. The fact that web sites run by small town U.S. newspapers picked up stories about the debate illustrates the dependence of these media on wire services. As Paterson (2005) illustrates, despite the proliferation of news sources heralded by the Web, wire services remain a major source of news – particularly international news – and many sites simply function as aggregators and distributors of news produced by these traditional sources. For instance, Yahoo News Canada relies almost solely on Canadian Press (CP) wires service – a news co-operative owned by the major Canadian newspapers – for its Canadian news. While Google News Canada draws from CP as well as a number of websites operated by major Canadian television broadcasters.

Lastly, with regards to which outlets were able to file stories within an hour of the conclusion of the debate, it's interesting to note that only one radio outlet was included by Google (discussing Duceppe). Further research is required to explain why such a bias in favour of daily newspapers exists. The absence of reporting from alternative sites, by comparison, might be attributed to the differences between alternative journalism and more traditional forms of reporting. As Deuze (2003: 210) illustrates, alternative news sites “offer not only their own news on line, but tend to critically comment upon the news offered by existing media networks.” At this level, alternative media focus on “journalism about journalism” rather than “hard” news that takes a seemingly objective or factual approach to events. Moreover, as Atton (2003: 268) points out, “the structural imperatives within which alternative journalism takes place… are quite at odds with the market-driven institutions of the mass media.” Consequently, in a work-a-day world where resources are scarce, focusing on “breaking news,” in the hope that being quick to report on an event will garner a larger audience or market share is not a priority. This is not to say that alternative media outlets are not concerned with reporting on breaking news or topical events. Rather, when they do – such as the Independent Media Centers reports on anti-globalisation and other protests – news tends to focus on issues of social justice or instances of civil disobedience in an effort to re-frame mainstream media’s interpretations of these events.

Another explanation for the lack of alternative outlets in online news aggregators like Google news relates to production, particularly in Canada, where there are very few alternative news producers. Only a couple of sites, such as TheTyee.ca and The Dominion (dominionpaper.ca) produce any volume of quality, original material. Others, such as rabble.ca largely act as news aggregators (though rabble.ca has been at the forefront of producing and circulating podcasts) or as Bruns (2005:17) terms them “gatewatchers”, and work to identify and “gather important material as it becomes available.” And still, to a large degree, these sites provide news commentary, not “hard” or breaking news.

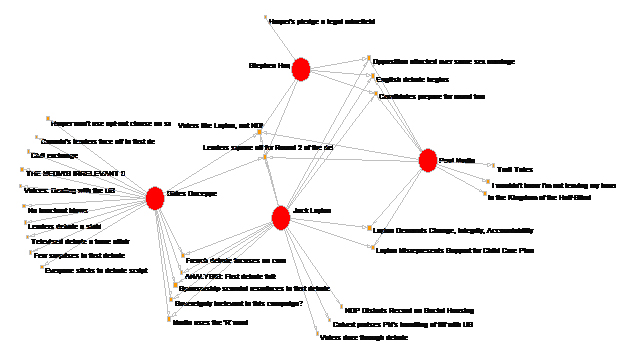

Figure 2 : First English Language Debate, Leader X Headlines, Dec. 17, 2005 (click image for full size version)

For the second analysis, above, Figure 2, we investigated the coverage of the same debate and political leaders, as represented by story headlines. This map provides insight into online news discourse and framing of the election debate – key terms that are often repeated across media attempting to answer the age old question: who won the debate? To this end, the most central story, which mentioned all of the party leaders in the debate, was “Voters like Layton, not NDP: poll”. The other most commonly shared story headline was the generic “Leaders square off for Round 2 of the debate game”. The story “Voter like Layton, not NDP: poll” was published by the Toronto star, one of the country's largest and most influential daily newspapers. “Leaders square off for Round 2 of the debate game” was posted by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the national public broadcaster (TV and radio). The map also shows that Jack Layton, who leads the smallest party in Parliament, achieved good name recognition and resonance in online headlines one hour after the English language debate. However, the headlines that discuss both Layton and Martin in this map show two sides of that resonance: “Layton Demands Change, Integrity, Accountability”, compared with the more negative “Layton Misrepresents Support for Child Care Plan” and “NDP Distorts Record on Social Housing.”

In terms of headlines that touch upon campaign issues, Martin, Harper, and Layton are all mentioned in the story entitled “Opposition attacked over same sex marriage.” The two main party leaders effectively vying for the prime ministership, Martin and Harper, together and separately, are only linked to one campaign issue in online headlines one hour after the debate: same-sex marriage. Duceppe and Layton were most associated with the other hot button issues leading into the election campaign, a patronage scandal within the ranks of the governing Liberal party and the perennial and divisive issue of Quebec sovereignty. As previously noted, Duceppe association with many stories concerned with the format and dynamics of the debate itself, again reminds us of the self-reflexive nature of the media reportage on election debates – that is, media reporting about the stage or format of the news event itself. Layton, for example, is also mentioned in the story entitled: “Voters doze through debate”. Lastly, although the Bloc Quebecois only ran candidates in the predominately French speaking province of Quebec (75 of 308 ridings), overall their party leader Gilles Duceppe, received the highest volume of online news coverage by Google one hour after the English language debate. This is very likely the result of his heightened coverage from the French language debate that took place the night before.

Methodologically speaking, this 'headline' map also raises further questions about the Google ranking method. Specifically, we were puzzled to find that in a small number of cases our search terms for a specific leader returned headlines that in fact mentioned another leader. For example, a headline leading with "Harper won't use opt-out-clause on same sex" is returned in relation to Duceppe, while a headline including "Martin uses the R word" is linked to Duceppe and Layton. After reviewing the original stories it was clear that the query-leader was present in the body of the story, but not in the headline. One possible explanation is that factors such as the reputation of the news outlet or other ranking criteria resulted in these unusual linkages. In any case, at this stage of the research the question of how search terms return news stories, that is the functioning and logic of Google's ranking algorithm, was again called into question. In other words, if we search for "Paul Martin" why does Google not return stories that have Martin in the headline, teaser text, or full text of the story?

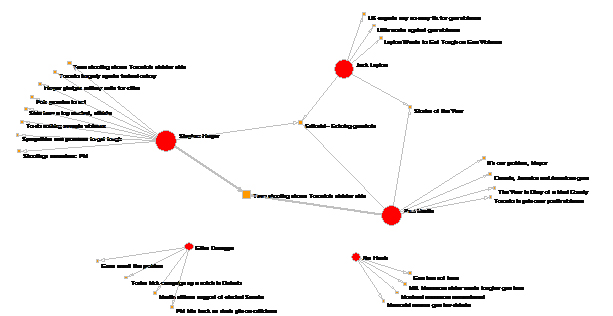

Figure 3 : Top online headlines associated with each leader on the issue of gun violence, December 29, 2005 (click image for full size version)

In addition to the leaders debates, we sought to include coverage of an evolving event or issue that confronted the candidates during the course of the election campaign – a much less predictable, scheduled, and scripted event. For this reason we chose to focus our research on the framing – via story headlines – of the gun violence issue. To begin with, we found that the media framed each respective leader in a different light, in other words there were few headlines that brought together coverage of more than one leader. The vast majority of the media stories on this issue were focused on one respective leader’s reaction to the shooting, not a debate between leaders or their party positions. The Conservative party leader Stephen Harper (whose Conservatives would go on to win the election, however they were only able to form a minority government in the Canadian House of Commons) had the most resonance and connection to the issue of gun violence in online news. In the days following the shooting (research conducted December 29th) Harper had the most coverage. This may be related to Harper’s quick return to campaigning after the holiday, whereas the other leaders took more time off over the traditional holiday break. More importantly, Harper's coverage in the news headlines emphasised his active plans to respond to the issue. For instance, in the National Post, one of Canada's two national newspapers, Harper's coverage included the headlines: “Sympathies and promises to get tough”, while the Toronto Star exclaimed “Harper Pledges Military Units for Cities”. Layton was also cited in media stories discussing tougher action: “Layton Wants to Get Tough on Gun Violence.” (CFRA radio). The incumbent, Martin, however, registered no headlines that included a call for action. Gilles Duceppe and Jim Harris (the Green party leader excluded from the leadership debates) were not widely cited by the media (compared to the other candidates on this issue). Harris, however, was linked to the gun ban issue and its relation to the anniversary of the shooting of female students at a university in Montreal.

Conclusions

This brief paper set out to provide insight into the possibilities for online research within, alongside – and as a critique of – existing mainstream online information and news aggregators. Our goals were three fold: first, we sought to provide an outline of new research methods for studying digital news. Much of our research would not have been possible without experimental, small scale, research software tools that disaggregate or otherwise strip the web – and its content – of the interconnection between the interface design and the algorithmic rankings of search returns (the seemingly naturalised promotion of certain stories and outlets over others). Such tools, moreover, enable the viewing of discrete aspects of digitised new stories, eg. codes and tags in their html text that explicitly state their location, their date of publication, the type of news outlet/wire service, the hosting location, etcetera. Such data, as we have seen above, compared, correlated, and visualised can offer intriguing insights into the mode of production of digital news, the coverage of social issues around the globe, and the relation of news outlets to one another. Given the amount of material produced by such online news aggregators today, we argue that the need for such disaggregating info-tools will only increase in the future.

Second, as Google's search engines have gained tremendous popularity, not to mention profit generating capacities, critical research is required to determine the limits and potential biases of such services. As a business Google maintains close watch and guard over its proprietorial algorithms and corporate partners, the reasons why certain stories and news outlets receive more favourable placement on their news portal will very likely remain a mystery. However, given the patterns revealed here, future research that compares news coverage across online news aggregators or through other news/information databases is needed to better understand the rankings and omissions these services provide.

Lastly, recognising the clear limitations with our sample of news stories, we would argue that the research presented herein, investigating the coverage of the Canadian federal election, nonetheless offers some compelling findings. We were particularly intrigued by the stark differences in coverage that leaders received with regards to the campaign issues. The question of news "forms" also resonated with our general understanding of the public mood and view of the incumbent Liberal party leader's perceived association with P.R. tactics and other forms of electoral machinations. Our findings also pointed to the relatively broad coverage received by all the major party leaders, albeit with some receiving perhaps less than positive language (eg. Layton).

Thus in conclusion we tend to agree with Paul's (2005) view that on-line news is still far from reaching its potential as a “cutting edge news vehicle” as forecast by digital pioneers in the mid-1990’s. As she illustrates, rather than providing more background and context to news stories, new news formats, or hyperlinks related materials, on-line news generally “comes to the screen after it has been edited for print” and thus acts to simply extend the reach of newspapers. In the wake of the ongoing convergence of print and broadcast media, the propensity of commercial news organisations to “repurpose” material produced for one medium for use in another serves to even further reduce the range of perspectives available in media (Skinner, 2004).

References

Atton, C. (2003) “What is Alternative Journalism?” in Journalism vol. 4 no.33 pp. 267-272

Bruns, A. (2005). Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production, New York: Peter Lang

Cooper, Mark. (2003). Media Ownership and Democracy in the Digital Information Age, Center for the Internet and Society, Stanford Law School, cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blogs/cooper/archives/mediabooke.pdf, accessed April 27, 2006

Deuze, M. (2003) “The Web and its Journalisms: Considering the Consequences and Types of Different Newsmedia On line” in New Media and Society vol.5 no. 2 pp 203-230

Entman, R. (1993) “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm” in Journal of Communication 43 pp. 51-58

Gamson, W. (1989) “News as Framing” in American Behavioral Scientist vol.33 no.2 pp 157-161

Glaser, M. (2005) “Inside Yahoo News: Aggregator Brings RSS to the Masses” in Online Journalism Review, http://www.ojr.org/stories/050331, accessed April 27, 2006

Menashe, C.L. (1998) "The Power of a Frame: An Analysis of Newspaper Coverage of Tobacco Issues- United States, 1985-1996” in Journal of Health Communication vol. 2 no. 4 pp. 307-325

Patelis, K. (2000) “E-mediation by America Online” in R. Rogers Ed. Preferred Placement: Knowledge Politics on the Web, Maastricht: Jan Van Eyck Akademie Editions

Paterson, C. (2005) “News Agency Dominance in International News on the Internet”, in David Skinner, James Compton, and Mike Gasher (Eds.) (2005) Converging Media, Diverging Interests: A Political Economy of News in the United States and Canada, Lantham: Lexington Books

Paul, N. (2005). “'New News' Retrospective: Is Online News Reaching its Potential?”, Online Journalism Review, http://www.ojr.org/ojrstories/050324paul/print.htm, accessed April 26, 2006

Rogers, R. (2004) Information Politics on the Web, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1-33.

—— and Ben-David, A.“Coming to Terms: A conflict analysis of the usage, in official and unofficial sources, of 'security fence,' 'apartheid wall,' and other terms for the structure between Israel and the Palestinian Territories,” unpublished ms., 2005. (http://www.govcom.org/full_list.html)

Saguy, A.C. & Riley, K.W. (2005) “Weighing Both Sides: Morality, Mortality, and Framing Contests over Obesity” in Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law vol. 30 no.5 pp. 869-923

Schudson, M. (2003) The Sociology of News, New York: W.W. Norton

Skinner, D. (2004) “Reform or Alternatives? Limits and Pressures on Changing the Mediascape” in Communique, Union for Democratic Communications vol.19 pp. 14-38

Tuchman, G. (1978) Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality, New York: Free Press

White, D.M. (1964) “The 'Gatekeeper': A Case Study in the Selection of News” in Lewis A.D. & David W. Eds. People, Society and Mass Communications, London pp 160-172.