We have learned to be suspicious of the photographic image. Long before the burgeoning of digital technologies, when photography was still in its supposedly “trustworthy” analogue phase, theorists and critics as diverse as John Tagg (1980), Christian Metz (1982), Roland Barthes (1982), Laura Mulvey (1975) and Susan Sontag (2001) each in their individual ways advocated deep suspicion towards the photographic image in both its still or moving forms. Broadly speaking they proposed the photographic image as governed by the dynamics of voyeurism – the power and the pleasure resided with the spectator, to the likely detriment and disempowerment of the looked-upon.

General distrust towards the photograph image at large becomes more pointed in regard to the photographic portrait. Susan Sontag’s maxim, “to photograph people is to violate them,” (Sontag 2001:14) crudely but accurately encapsulates the broad misgivings held towards the portrait photo. These arguments become particularly apposite in relation to photography whose overt purpose is to measure, surveil, classify, control, repress, inhibit and/or normalise subjects — which includes the photography produced in hospitals, barracks, penitentiaries, asylums, “slums”, photographs made by nineteenth century explorers, anthropologists and ethnographers, by modern ‘security’ agencies, and so on. Of these, the police “mug shot” is one of the most obviously and expressly authoritarian.

In the mid nineteenth century police departments worldwide began systematically compiling “rogues galleries” and mug shot photo books. A number of writers (including Tagg 1980 and Gunning 1995) have pointed out how crucial this moment was in both “disciplining” the criminal body and more generally, in fixing the modern conception of individual identity. Tagg, in particular, has applied Foucauldian (1985) notions of discipline and surveillance in his study of the uses to which the photographic apparatus were put in the nineteenth century. The systematic linking of the reliably objective visual or bodily record with the scrupulously maintained bureaucratic archive that nineteenth century police established is the pro forma for all modern citizen identification systems. It is also a pro forma for virtually all modern surveillance systems, and fixes the process by which we construct ourselves as surveilled subjects.

This essay uses a collection of archival police “mug shots” to examine the relationship between the subjects of these photographs and the photographic apparatus. By extension, this relationship embraces the relationship between photographic subject and the police photographer, and that between the subjects “captured” in these photographs and the viewer of the photographs themselves. My analysis considers the exhibitionism displayed by many of the individuals photographed in this collection. Many previous studies of photography, including archival photography, have privileged the voyeurism, surveillance and control implicit in the photographic process. As a result, the selfhood of the photographed subject has often been elided. My analysis here explores those aspects of display or expression of selfhood apparent in the subjects brought before the police photographer.

***

Around a hundred thousand negatives taken by NSW police photographers in the years between 1912 and the late 1960s reside in the loft at the Justice & Police Museum in Sydney, where they have been since they were taken from a government warehouse in 1989. The subjects of the photos include fingerprint records, ballistics specimens, photographed documents, scenes of fires and industrial accidents, close-ups of recovered stolen goods and items of evidence, road accident scenes, photos taken at official police functions and ceremonies, portraits of senior officers, and so on. This essay is concerned with the 6” X 4” glass plate mug shot negatives produced in New South Wales prisons and police stations between 1912 and 1930. This essay deals in particular with the latter group, police station mug shots, referred to in police literature of the time simply as “Special Photographs”.

The collection is large, unaccessioned, and much of it, particularly the pre-1940s sections is disordered. Research is still at a largely exploratory stage. Documentation has not yet been found which might explain the operating procedures for early Sydney police photographers or the criteria they used in deciding who and what to photograph. Most of the older images in the collection have no case numbers, nor any traceable cross-references to police briefs. So far most of the information about the “why, what, who and where” of the photographs comes from their observable intrinsic pictorial content. Further research into the NSW Police history, the history of the camera in Australia, the history of forensic and institutional photography worldwide, the technical production practices and the broader discourses which informed Sydney police photographers, biographies of individual photographers, the characters and practices of the Sydney criminal milieu, and the specifics of individual criminal cases, will no doubt add to our understanding of the Special Photographs. At the moment most of our information comes from the images themselves, and therefore must be in part speculative.

Over a four year research period, I examined around two thirds of the pre-1950 section of the NSW Police forensic archive — around fifteen thousand glass plate and acetate negatives. They are in poor condition — many are water damaged, mildewed, chipped or broken. The largest part of the research process involved taking a few boxes of negatives at a time (a box contains anywhere from10 to 50 glass plate or acetate negatives) and examining each negative on a lightbox, taking notes. However careful and procedure-bound one tries to remain, such work is done in a state of mixed excitement and anxiety. Every single negative, each photographed document (these include vintage blackmail notes, obscene suggestions, routine business letters, indecipherable scribbles and so on), each shot of a back alley, city street, domestic interior, indeed every fingerprint specimen recorded in the archive presents a potential story waiting to be researched and explicated.

As well as these external valencies, the negatives possess great detail, which continually beckons the researcher to explore ever more intensively within the frame. The large format, fine-grained glass plate negatives allow for considerable enlarging, and the seemingly endless discovery of detail: buildings, shop and street signs, billboards, tram and bus route numbers, fabric patterns, discarded newspapers and bits of detritus, framed portraits on domestic walls, posters on telegraph poles, and bystanders.

Mug shots comprise around a quarter of the pre-World War II negatives. These are on 6” X 4” glass plate negatives. Typically these have a name, a date and sometimes coded fingerprint data inscribed in black ink on the emulsion side (written backwards, so that the information prints the ‘right way’). The pictures, now between 75 and 95 years old, lie outside what we could reasonably regard as ‘living memory’. Little is known about the procedural directives which informed these photographs. We have only the negatives themselves, the occasional cryptic notes inscribed on them, or sometimes on the decaying cardboard boxes which house them to inform us as to their time and place of origin, and the reasons they were produced at all.

In the early stages of the research some perplexing patterns emerged. A box of negatives would surface, for example, all inscribed with the same date, showing young men, all with similarly longish hair, all of them wearing collarless shirts. Another series of negatives was found, showing older dishevelled, unshaven men, all inscribed “Bathurst”. I eventually concluded these were not, as I had first thought, young gang members, nor the homeless and indigent of Bathurst, but were in fact convicts, photographed in New South Wales prisons – such as Bathurst Gaol. They appeared equally because prisoners were only allowed a wash and a shave once a week. Once realised, it seemed quite obvious that these, and the thousands of mug shots like them, were prison portraits, but that realisation took nearly a year’s research to emerge.

Even when viewed in negative these prison images possess a great particularity – every pore and wrinkle, every hank of greasy hair, it seems, has been recorded. As historical documents, as instances of an important type in the evolutionary history of the photograph, and as gripping images, the prison mug shots are clearly of great importance. Yet I came to dread them. The refrain of defeat and despair became increasingly oppressive. The affectless convict stare seemed to convey neither acceptance nor even anger. If the subjects felt resentment at having their photographs taken, they mostly withheld even that feeling: one senses in the photographs an unwillingness to “communicate” with the photographic apparatus at all, a non-complying passivity, a refusal by the subjects to “let anything show”. The strict partitioning of the negatives into two or three views — face on, side on, full length — replicated the physical and psychic containment of their subjects. Encountering these images in large numbers, the truisms about the repressiveness and cruelty of the surveilling gaze, the charge that photography is inherently authoritarian and thanatotic became pointedly apposite.

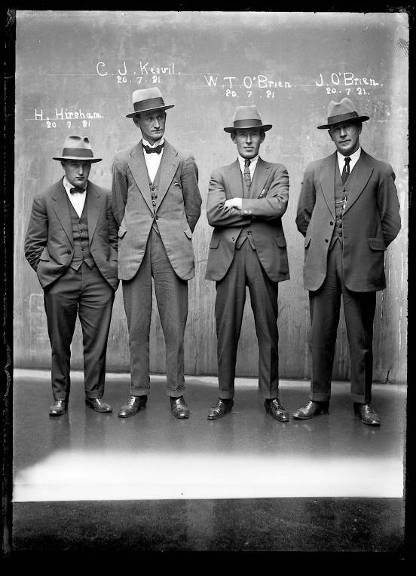

But meanwhile I was finding other boxes, fewer in number, of very different mug shots — individuals or small groups of often oddly assured-looking, often well-dressed men and women. So “in command” did some of these people seem I assumed they were detectives — special squads perhaps. It became clear, however, that the photographs had been taken in the cells of various inner city police stations, mostly at Central Police Station, in Central Street, Sydney. The subjects were people very recently (usually that same day) taken in custody. About two thirds of them seem to have been subsequently charged with a crime (that is, their names can be found in the court returns or charge listings in the NSW Police Gazette); the others were apparently released without charge. All convicts in New South Wales had been routinely photographed since the 1870s, but the Special Photographs seem to have been taken on an ad hoc basis, apparently at the behest of individual detectives. Over a thousand of the Special Photographs have so far been found in the collection, but the various numbering systems used on the negatives suggest that about three thousand portraits were produced up to 1930.

1 H. Hirscham, J. Keevil, W. T. O’Brien, J. O’Brien, 1921, Central cells

All the mug shots in the police collection, (ie, the prison portraits and the Special Photos) are of a generally high production standard, in sharp focus, and tonally well-balanced. We do know they were all taken by police photographers, and not outsourced. Nonetheless there are dramatic compositional and tonal differences between the two classes of portrait.

The prison photographs are arranged according to the Bertillon system. Criminal photography was largely standardised under the influence of French police records clerk Alphonse Bertillon, who incorporated the criminal portrait into a larger system of criminal identification, based on the careful recording of numerous facial and bodily measurements. With the widespread adoption of fingerprinting in the early twentieth century, Bertillon’s measurement system fell into disuse, but the “Bertillon photograph” — two or more views of the subject, one squarely facing the camera, another in profile — was by then the global police standard, and it remains so today.

The earliest of the Special Photographs are broadly “Bertillonian” in composition.

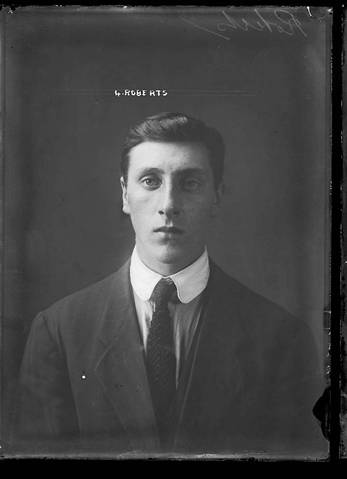

2 ‘Roberts’ Early Special Photograph, undated

3 ‘Roberts’

The portraits of ‘Roberts’ for example, taken around 1912, or perhaps before, accord with the “one-shot facing, one-side-on” Bertillon regime. There is also a nod here towards professional portraiture, evidenced in the high relief lighting and the carefully combed hair.

But by the very next series of negatives, found in a box labelled “11-20”, the style and composition departs dramatically from the Bertillonian standard.

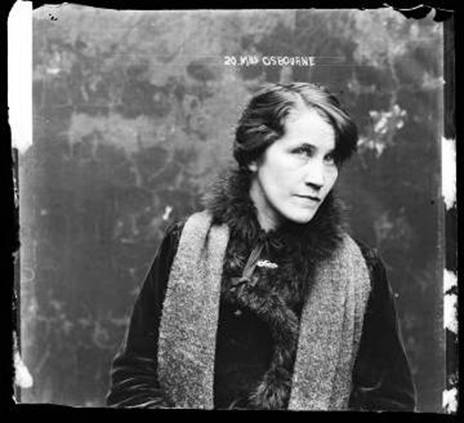

4 ‘Mrs Osbourne’. Details unknown

The picture of “Mrs Osbourne” remains a mystery. No female Osbournes (or “Osbornes”) are mentioned in the NSW Police Gazette for this period — the mid to late nineteen teens — and I wondered for a time whether, given the respectful ‘Mrs’ she might be a victim of crime, or an amnesiac. But the setting suggests otherwise. The cell wall behind Mrs Osbourne looks damp and distempered, suggestive of innumerable prior unhappy presences. The photographer presumably had to choose where exactly in the police station he would position Mrs Osbourne. (Has he put Mrs Osbourne where he feels she belongs?) At the same time, the subject’s almost silent movie star demeanour hints at a much more complex exchange between her and the police photographer. Indeed here, and in many of the Special Photographs we can see a marked degree of license at work, or staging choices, amounting at times to something resembling a police photographers’ mise en scene.

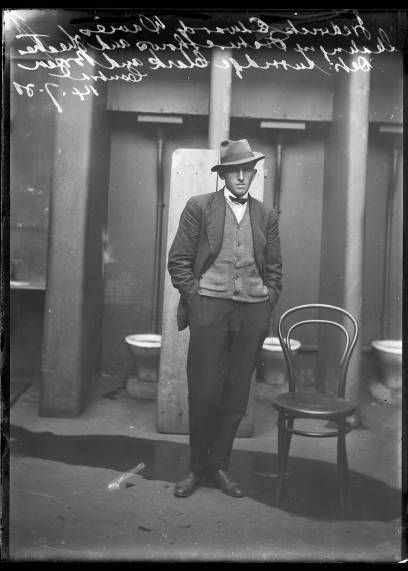

5 Frederick Edward Davies, location unknown, 1921

We might detect the disapproval held for subjects who are made to pose in front of toilets, leaky taps and drains — a radical departure from the photographic portraiture conventions of the day. The negative of Frederick Edward Davies is inscribed “Stealing in picture shows and theatres/ Dets. Surridge, Clark and Hogan, Central 14/7/21’” The low regard in which the police photographer holds the sneering, slouching sneak-thief Davies appears to be fully reciprocated.

Yet other photographs, despite the unpicturesque staging, seem to offer oddly warm views of their subjects.

6 Evelyn Courtney, possibly Newtown police cells, 1920

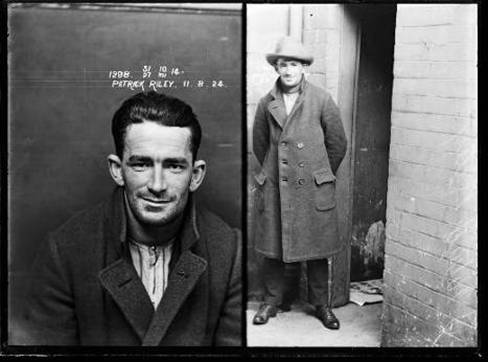

If we did not know otherwise, we might guess that Evelyn Courtney was dressed for a summer picnic, rather than appearing before Newtown Court on a stealing charge. Petty counterfeiter Patrick Riley’s self esteem appears undented, despite being made to stand in front of an open toilet door.

7 Patrick Riley, location unknown, 1924

At other times the subjects are framed in an almost flattering way. The mug shot of car thief Alfred Fitch showing him as a serious and resolute young man, clearly marked out from the soft focus background, might easily be mistaken for commisioned photographic portrait. Ten years after this photo was taken Fitch would be recorded in police literature as a member of the inner circle of the Darlinghurst criminal milieu, an associate of Frederick “Chow” Hayes and Kate Leigh, and with a reputation for violence. Other mug shots cast their subjects in what resembles an “Australian Legend” modality: as admirably no-nonsense, self-reliant young men of the bush labourer class.

8 Alfred Fitch, location unknown, 1924

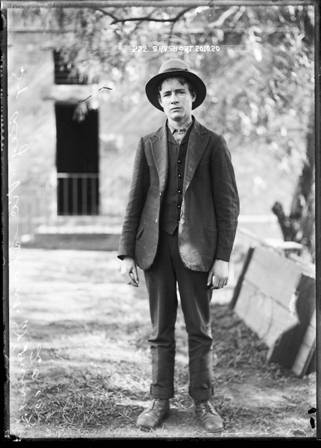

9 S R V Short, 20 October 1920, location unknown, possibly Darlinghurst Police Station.

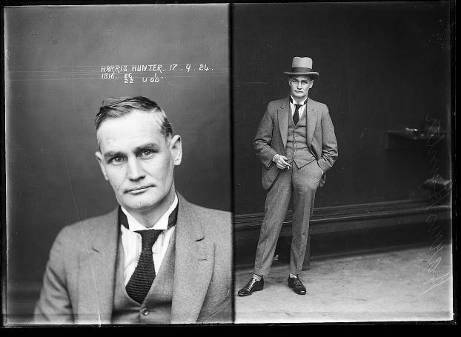

Harris Hunter, a receiver of stolen goods, is representative of another distinctive category found among the police station mug shots: well dressed subjects, seemingly at their ease, posing like successful bourgeoises.

10 Harris Hunter, Central cells, 1924

Although many of the mug shots are taken in what is recognisably the same general space at Central cells, no single compositional regime prevails. The framing is sometimes tight, as in the left hand side exposure of Harris Hunter (above), but other times the subjects are accorded considerable space within the frame. Their stances also vary greatly. After looking at a few hundred of such portraits, I began to suspect that these people had been allowed or perhaps invitedto assume whatever posture they might.

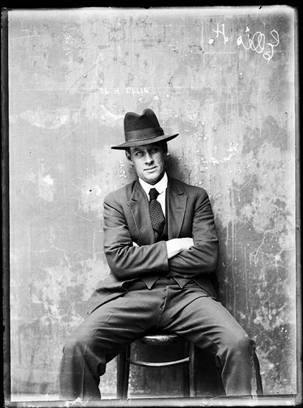

11 H Ellis, details unknown

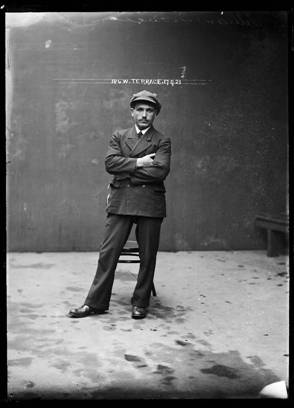

12 W Terrace, Central cells, 1921, details unknown.

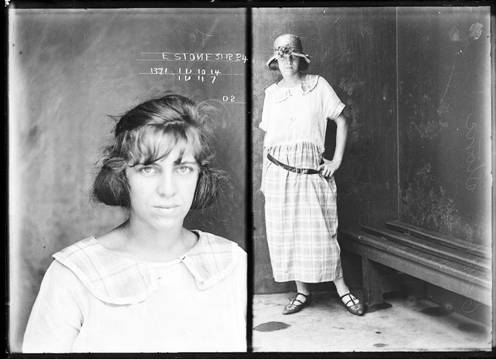

13 Edith Stone, Central cells, 1924, details unknown

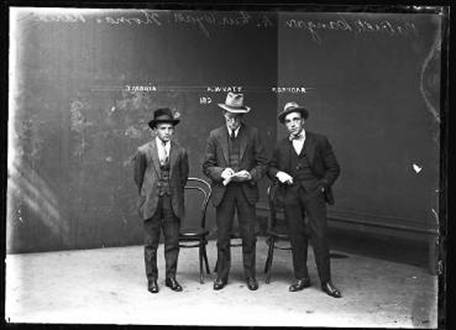

14 T Maria, A Wyatt and P Dangar, Central cells, details unknown

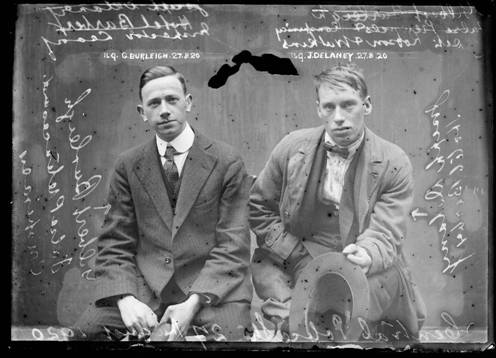

In some of the photographs a pugnacious, if not pugilistic dialectical tension is being played out. Gilbert Burleigh and Joseph Delaney (below) fill and almost control the frame. Delaney in particular, in this and its companion standing shot (not shown) displays a gangster movie ‘tough guy’ presence. But the photographer has hemmed the men in with his handwritten inscriptions, ‘false pretences’ for Burleigh, and ‘hotel barber’ for Delaney.

15 Gilbert Burleigh, Joseph Delaney, 1920, details unknown

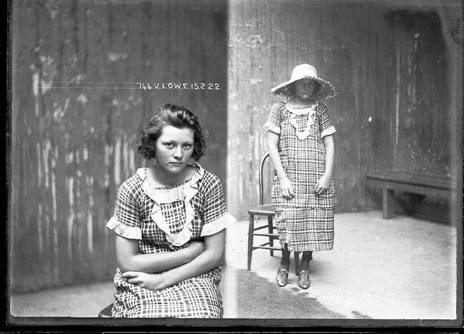

And yet at other times the photographs seems to record a great fragility in the subjects. In the photograph of Valerie Lowe, for example, and in many like it, we might detect an almost Dickensian take on the vulnerability of the young.

16 Valerie Lowe, Central cells, 1922

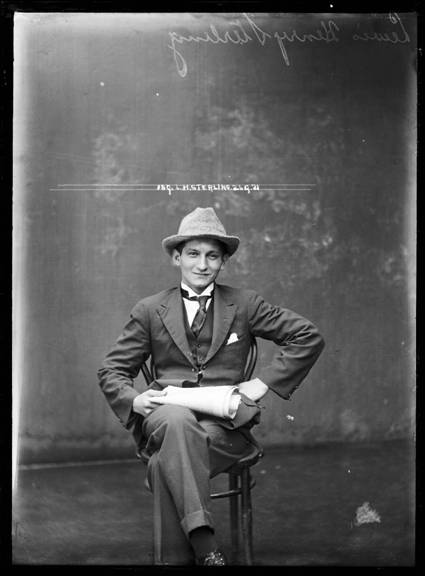

Among the most surprising are the many smiling subjects found among the Special Photographs, such as jaunty pickpocket and gunman Lou Sterling, a well-known crime figure of the 1920s

17 Lou Sterling, 1921 Central cells

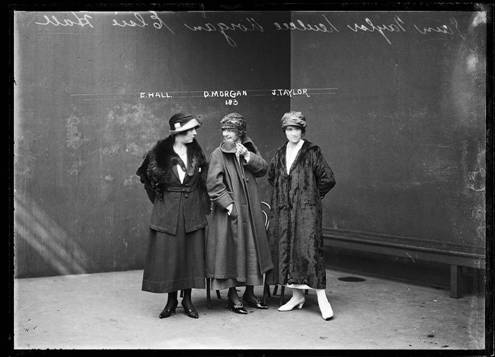

The three women seen below look almost as though they have stopped off at Central cells on their way out to a night on the town. Which was very possibly the case — the serial number on this negative, 183, follows that of the trio of men shown above (182), and it can be seen that the location and the lighting are identical. The six were possibly arrested together. Although no charges are listed in the Police Gazette against any of these names, the man in the middle, here labelled “Wyatt” appears in later mug shots, and is listed elsewhere in police literature as a false pretender and ‘suspected person’ named Brosnan (or Dangar). He and his companions ‘walked’ on this occasion however, and that expectation may account for the airy unconcern displayed by the entire party.

18 Jean Taylor, Dulcie Morgan, Elsie Hall, Central cells

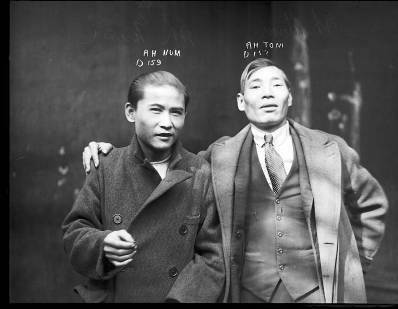

The photograph of “Ah Yum” and “Ah Tom”, apparently taken on behalf of Drugs Bureau detectives in the late 1920s, almost seems good-naturedly to contest then reigning stereotypes of the “oriental” subject. Neither name appears in the Police Gazette for the period, and the expectation of imminent release may in part account for their obviously elevated moods.

19 ‘Ah Num’, ‘Ah Tom’, location unknown

The young men in the photograph below were arrested and convicted for a warehouse break and enter in Glebe. Each of the trio seems to have his own particular relationship to the photographic apparatus, or perhaps to its operator. One is tempted to imagine, for example, that K B Lewins on the right has been snapped just as he is challenging the photographer to step outside.

20 Riley, Whittaker, Lewins, 1921.

Whether that particular fancy is correct or not, it is clear that the energy and vigour of the return gaze here produces a symmetry, or dialogic quality that, like the composition, is decidedly “non-Bertillonian”.

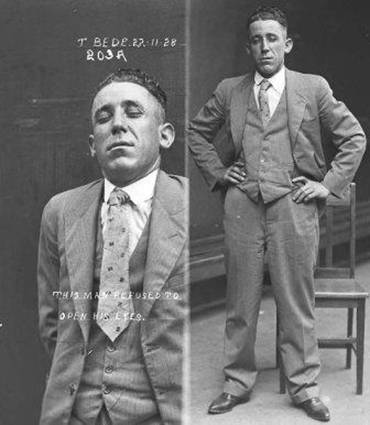

In some this forceful contract of gazes is further complicated through deliberate non-compliance. The inscription on Thomas Bede’s mug shot, uncharacteristically written over the middle of the figure, runs “THIS MAN REFUSED TO OPEN HIS EYES”

21 Thomas Bede, Central cells, 1928

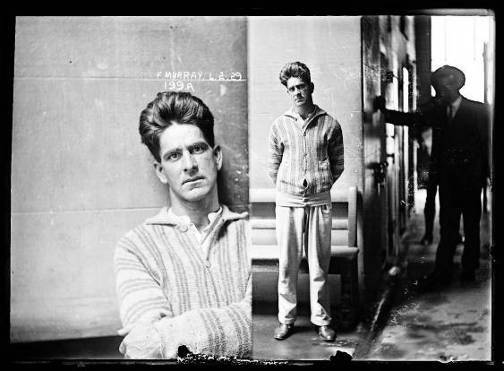

Sometimes the symmetry is disturbed by the accidental triangulation of sight lines, as when a policeman is included in the shot.

22 Frank Murray, location unknown, 1929

Or when some other third party is present. The derelict person in the background in this series of photographs, stirs occasionally, undermining the centrality of both cocaine dealer, May Blake, and “C. Home”.

23 May Blake, Central cells, 1930

24 “C Home”, Central cells, 1930

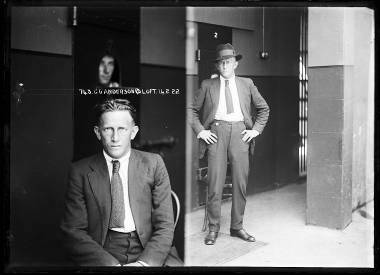

In a sequence of half a dozen shots taken at Paddington Police Station in 1922, the same unidentified prisoner peers out of the peep hole in the cell door in the background – intended to enable his captors to surveil him — as one after another subject is paraded in front of the camera outside his cell.

25 C Anderson and unknown prisoner, Paddington police cells, 1922

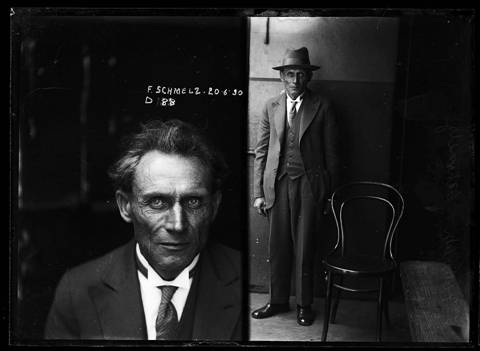

Not all the Special Photographs show confident subjects; some of the people depicted seem engulfed in despair or shame; a number of the Drugs Bureau photographs show “weathered”, addled or even physically contorted subjects. (These were taken at the height of the 1920s cocaine craze in Sydney).

26 F Schmelz 20 June 1930, location unknown

Yet in nearly all cases the subjects’ affectivity — be it one of apparent cockiness, shame, aggression, despair, amusement or detachment — seems to fully occupy the picture space, to powerfully declare itself in the medium, to ‘overwrite’ the frame. Alfred “Tiny” Ladewig, for example seems caught up in an ennui so profound as to be almost transcendent. We know that Ladewig was indeed destined for a prison sentence when this photograph was taken, for “stealing by trick”, and the empty, out of focus space which surrounds him here lends the photograph a further poetry.

27 Alfred Ladewig, 1921

***

In the essay “Cinema of attractions”, Tom Gunning contests the privileging of voyeurism in considerations of cinema. We would do well, he says, to consider also the complimentary impulse of exhibitionism. He suggests that we take this notion of “exhibitionism” in its most literal, prosaic sense (referencing cinema’s origins in the fin de siecle side show attraction) as well as in the psycho-analytic sense, the desire of its participants to “show themselves”. Gunning’s approach here echoes the work of previous theorists such as Erving Goffman (1959), who proposed a dramaturgical model of social behaviour, whereby social agents “impress” themselves on others in given situations.

All these mug shots — whether taken in prison or the police cell — are the product of a state surveillance project, and were certainly not intended at the time to be publicly exhibited. And in the case of the prison photographs we see little evidence of any complicity in the photographic process. These images are largely defined by the overt mechanisms of surveillance and control, and our engagements with them, however well-meaning, remain asymmetrical — our comfort counterpoints the manifest wretchedness of the subjects. At the same time the very manifest agency of the subjects in so many of the police station photographs, their “exhibitionism”, makes them surprisingly buoyant artefacts. We talk about “taking” photographs, but the Special Photographs have about them something of the given.

As well as the official public eye gazing at the subject here, we might also detect the workings of a more private eye, that of the police photographer himself, in the presence of the arrestee. The arrestee looks back at him — at another breathing, potentially vulnerable presence, towards whom he or she may have thoughts and feelings. The emulsion coated photographic plate from which the image is struck is strategically placed in that hot zone of exchanged looks. The photographs are like readings, or core samples, of that charged moment. The Special Photographs, again and again have position their subjects as complex, animated, restless, mobile co-inhabitors of the space they share with the photographer.

The generously framed photographs are also rich in context, which makes them in many ways the direct opposite of the Bertillonian criminal photograph. In his essay on photography, detectives and early cinema, Gunning points out that

[c]onstructing a method which could use photography … in order to fix an identity and individualize a subject depended on overcoming photography’s tendency to capture the contingent and ephemeral, on substituting some core of identity for the mobile play of features. …[T]he photograph was simultaneously too poor and too rich a form of evidence to the supply the easy means of identity a modern police department required. (1995: 29)

The Special Photographs are rich in the contingent and ephemeral. We see cigarette butts and discarded newspapers on the floor, graffiti on the cell wall, stitch marks and repairs evident in the subjects’ clothing, minor scars and blemishes on their skin. Their facial expressions and stances we see are complex and nuanced. Other prisoners or policemen are sometimes seen lounging in the background, the photographer’s camera case sometimes on the bench behind the subject. Combined with the informality of the poses, the Special Photographs seem to offer an almost “natural history” view of the subjects, one which sees them not as decontextualised objects for measurement, but as actor/participants in a kinetic, fluid interaction with their physical and human environment and with the world.

For reasons unknown, literally only a few mug shots taken after 1930 — whether prison portraits or Special Photographs — have so far turned up in the Justice & Police Museum collection. The few later Special Photographs we do have, which are from 1933 and 1934 bear little similarity to the earlier series. They are tightly framed, show only head and shoulders, and are taken under an unwavering, flattening, presumably artificial light (rather than the natural light that filtered through the open skylight at Central cells, varying in intensity according to season and time of day). The Special Photographs dating from 1930 or before, however, although produced by a succession of photographers, display a consistently non-Bertillonian character, even though the postures and positions of the subjects vary greatly. The one composition style which does not appear is the Bertillonian, as though the police photographers were expressly avoiding that particular arrangement.

Happenstance has further “de-Bertillonianised” this group of photographs. As Gunning (1995), Sekula (1986) and Tagg (1980) have pointed out, the use of the photograph as a means of establishing identity depended not so much on some almost metaphysical power of the surveilling gaze, but on the photograph’s integral connection to a carefully maintained information archive; it is not the photographic gaze alone which ‘controls’ and surveils, but the photo as element in a larger bureaucratic information system. “The central artifact of this system”, offers Sekula (1986: 17, quoted in Gunning 1995: 29), “is not the camera but the filing cabinet.” The fact that the Sydney Special photographs have been long since cut adrift from their information systems in a sense liberates the subjects. As far as we know, there no longer exists a filing cabinet — we cannot look up the photographs’ serial numbers or the subjects’ names in a central database.

Today the Sydney police Special Photographs are under the custodianship of a different state government instrumentality, the Historic Houses Trust of NSW. Although they began as ‘police eyes only’ images, now they are to be part of an “exhibitionist” project roughly of the sort Gunning describes: a museum exhibition and a companion high production value, large format publication, both of which feature, along with other forensic images, a number of the Special Photographs. Thus a most unlikely coterie of shadowy, fleet-footed sharpers and “lurk merchants” of eighty years ago are poised to become boutique “heritage icons”, promoted by the same State government which once sought their imprisonment. The publicity department responsible for promoting the exhibition chose the portrait of H Ellis (reproduced above, fig 11) as the lead image for the promotion, what is called in publicists’ jargon the ‘hero image’. The rehabilitation of H Ellis from 1920s Sydney villain to twenty first century Sydney hero well encapsulates the ironies attending the entire project.

***

In my encounters with the Special Photographs I have been moved to think of that enterprise in “vital recording” which was going on at the same historical moment that these photographs were produced, the so called “race” and “hillbilly” music recording explosions of the 1920s and 30s in the USA. Field trips by recording companies to the US south and talent spotting expeditions to juke joints and city night clubs produced a huge new body of recorded music, radically different from the Tin Pan Alley music of the day. This recorded work, to the great surprise of the recording companies, enjoyed a circulation way beyond the communities from which the performers themselves came, and changed the way audiences worldwide understood music ‘records’.

Here is one way of seeing what was achieved: in active complicity with sound recording engineers, these unconventional, sometimes highly eccentric artists rendered traces of their being, in its most intimate particularity, onto the recording medium. The energetic assertion of selfhood and everyday idiosyncrasy before the apparatus that artists like Billie Holiday, Jimmie Rodgers, Tampa Red, the Carter Family, Uncle Dave Macon, Robert Johnson and many others achieved was wholly new to sound recording at the time. It has since become so much the benchmark of the “recorded authentic” that it is easy to forget how suddenly it appeared, and how radical a departure from commercial recording and performance practices it represented. A number of writers, including Sean Cubitt (1984) have remarked that the more “intimate” and “invasive” the sound recording apparatus became, so, paradoxically, did it allow for an unprecedented amplification and dispersion over time and distance of the recorded presence. Others — including Greil Marcus, Geoffery O’Brien and Bob Dylan — have recently (re)turned their attention to this “other side” of jazz age recording, the music of what Marcus has called “the old weird America.” The success of so many of those then obscure performers in addressing themselves to the recording apparatus, their ability not to be cowed, to resist the invasive violence of the medium undermines the simple assertion that recording media must serve the perverse interests of those who wield it, to the necessary detriment of those whose sonic or visual likenesses are “captured”. To ignore or discount the agency of those recorded is to misrepresent the process.

The music of those often socially “outsider” performers of the twenties contains many celebrations of rascality and villainy – of drinking, drifting, gambling, whoring, reefer-smoking and cocaine-sniffing. And not a few of the artists lived lives not so different from their exact contemporaries in Sydney, the people we see in the Special Photographs. Those people, finding themselves in a despotic territory, “impressed” their selfhood onto the recording medium of the police mug shot. The everyday rogues, prostitutes and cocaine sniffers of Sydney’s jazz age did not leave much in the way of a musical or poetic record of their daily lives. Nonetheless, some of these photographs have a way of ushering us just as magically into their presence, and them into ours. And that encounter will always be at least partly on their terms.

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland (1982) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography; trans. Richard Howard, London: Jonathan Cape

–Mythologies, (1972) trans. Annette Lavers, London: Jonathan Cape

Cubitt, Sean (1984) ‘”Maybellene”: meaning and the listening subject’ in Popular Music, 4, 207-24

Dylan, Bob (2004) Chronicles New York: Simon and Schuster

Foucault, Michel (1985) Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, (Alan Sheridan, Trans), Harmondsworth: Penguin

Goffman, Erving (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life New York: Anchor

Gunning, Tom (1989) “The cinema of attractions: early film, its spectator and the avant-garde” in Early Film, Thomas Elsaessar and Adam Barker (eds) London: BFI, 56-62

—(1995) “Tracing the individual body: photography, detectives and early cinema”, in Charney, Leo and Schwartz, Vanessa, (eds) Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp15-45

Marcus, Greil (1997) The Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes New York: Henry Holt and Co.

Metz, Christian (1982) The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, trans. Celia Britton, Annwyl Williams, Ben Brewster and Alfred Guzzetti, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Mulvey, Laura (1975) “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Screen 16:3, Autumn, 6-18

O’Brien, Geoffery (2004) Sonata for Jukebox: Pop Music, Memory and the Imagined Life. New York: Counterpoint

Sekula, Alan (1986) “The body and the archive”, October, 39 (winter 1986): pp3-86

Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Tagg, John (1980) “Power and photography: part one, a means of surveillance: the photograph as evidence in law” in Screen Education 36 (winter 1980) pp 17-55

Images courtesy of Historic Houses Trust NSW and NSW Police Service.

Links

See also ‘The Joliet Prison Photographs, 1890-1930’ at http://www.jolietprison.com/default.asp and http://www.jolietprison.com/publications/catalog.asp

‘One Big Self: The Prisoners of Louisiana,’ photographs by Deborah Luster at http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/David_Winton_Bell_Gallery/luster.html

http://www.edelmangallery.com/luster.html

A large number of contemporary and historical mugshots are at http://www.mugshots.com/