Introduction

This paper is about what is gone. It is about a world that is lost. It is a about a earlier time, when photographic equipment was heavy, clunky and difficult, and night time photography was frequently augmented by a magnesium powdered “flash” that sent up a smouldering trail of smoke over a scene-of-crime or vehicle crash. It is about everyday moral defeats, deaths, accidents, smashes, collisions, lost souls, missing people, who populate sad, whimsical, hilarious, horrifying and uncanny images. It is about the capacity for unflinching seeing that constitutes the rigid discipline and technical excellence of the forensic photographer. It is about photography as testimony, photography working as a rationally-based evidence collecting activity, but also about each crime scene photograph as a receptacle for catching and commemorating something more; atmospheres that are disturbed and wounded, scenes not of visible horror, but of horror suspected, of horror that has recently happened but is no longer evident.

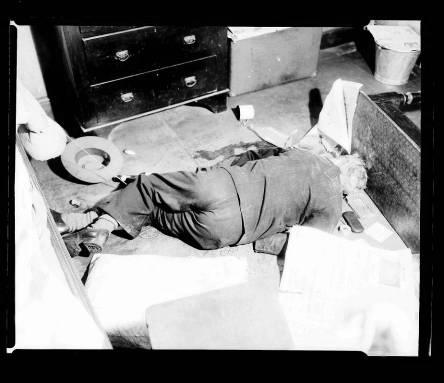

The squalor of death in the toilet: we do not know if the cough mixture bottle lying parallel to the left leg of the deceased is there for medical reasons or to provide a pleasing illicit euphoria? Is the blood on the shirt due to a burst of consumptive coughing or is it the result of a violent bashing?

MethodologyThe paper has two contrasting sections. The first, celebratory, didactic and theoretical by turns, attempts to place the photographs from the Justice and Police Museum forensic photography archive in a broader social-historic and cultural framework, offering observations on where in the visual history of the twentieth century these intriguing images may be situated. Questions that are raised by the “rescue”, “re-presentation” and “aesthetic canonisation” of crime-scene photography and its insertion into the arenas of art, publishing and museology are examined here and, several different approaches toward interpretation considered. In the latter half of the paper “hard” theory is left behind for a more personal and conversational engagement with the photographs. Here over 20 images from the archive are surveyed, and their visual structure, aesthetic codes and narrative potentialities annotated. Both unambiguously violent photographs as well as those that are enigmatic and poetic are treated here.

Finally it should be noted that this paper is more “speculative” than “definitive” in scope. Much work still remains to be done on the archive. A more summative offering in the form of book and exhibition will shortly be available. In the meantime this piece of writing should properly be regarded as a report from the margins of an archaeological site as the first few layers of vast and significant historic image lode are excavated, excitedly sifted, and contemplated. With this in mind absences and lacunae may readily be encountered ahead.

Background to the CollectionWithin the mid-nineteenth century sandstone precincts of Sydney’s Justice and Police

Museum, at the top of a narrow iron staircase, there resides a dimly lit space known as the “loft”. Inside this room ranged on towering bays of shelving is a comprehensive crime photography archive of over 100,000 glass plate and acetate negatives that covers the period 1912 – 1964. This crime photography archive grew from the efforts of the NSW Police Scientific Investigation Bureau (established 1938) and from the earlier documentation activities by police and prison photographers, primarily engaged in criminal portraiture (“mug shot” photography). The archive is currently being researched toward a 2005 book and exhibition that will be titled City of Shadows: a joint collaboration between the museum and author, Peter Doyle. Even the briefest sampling of the many boxes that line the loft’s shelves reveals that this archive’s mass of glass, silver emulsion and acetate is strongly concerned with the scrutiny and dissection of urban and suburban space. Thus in part, the archive offers an architectural and social geographic mapping of many sectors of pre-gentrification inner Sydney between 1920 and 1940 revealing a world of lost buildings, mean streets, and shabby laneways. While in later images taken between 1940 and 64 of Sydney’s outer suburbs, the roving eye of the forensic photographer increasingly discovers, dissects and documents the ragged edges and nondescript no-man’s- lands of the growing metropolis.

The collection is particularly rich in shots of back-lanes from depression era Sydney, always curiously depopulated when the detectives are about.

Missing Official RecordsA very important fact about the archive is that the records and cataloguing systems that once accompanied the images no longer exist. However although we lack supporting documentation, much can be learnt about the technical approach taken to earliest manifestation of forensic photography in NSW (1920-38). Certain visual habits and rhythms swiftly become apparent. We confront a signature style of probing the optically charged grid of the crime scene. We discover how the heavy wooden tripod and bellows lens of the photographer, often starts off the recording of the scene with an establishing shot of general environment, before being restlessly and obsessively repositioned, circling inward to the exact spot where the deceased lies or the vehicles have collided, in order to trap every vestige of evidence beneath the powerful flare of the flash lamp.

Indeed, the hungry focal plane of the lens not only seems to gather in the visible detritus of the scene, but to also to commemorate what can only be described as its metaphysical residue: an atmosphere of malignance, which hangs over the zone of violation, like a sinisterly humming musical chord. In their pictorial exhumation of the dark soul of a city then, these crime archive images are about freezing fields of disturbance in time via the click of the shutter, resolving profound behavioural mysteries, and revealing what lurks beneath the ruptured surface of urban reality. The aesthetic of these images is often unconscious and uncrafted but is nonetheless undeniably present: an integral part of their power as visual documents.

Scenes of Crime and Associated Visual CulturesThe images within the Justice and Police Museum crime photography archive possess certain congruities and conduct a resonant (if unintentional) dialogue with much better known and more widely celebrated images, and phases of creative engagement, from the broader histories of photography and cinema.

Sydney cops straight from noir central casting, play out a pick pocketing scam for the lenses edification.

Many of these photographs seem startlingly familiar. They seem to both pre-date and anticipate the visual codes of film noir (and neo-noir) while also possessing strong parallels with the photojournalistic practice of New York’s Weegee. Weegee has been well described as a “hard bitten news photographer, aficionado of the New York City underworld, and urban story teller par excellence” whose crime based photographic oeuvre (published in the book Naked City, 1945) records chaotic highs and lows of life in the “urban matrix” along with its “fires, car-crashes and murders”. (Barth et al: 2000: 148). And although the images in the Justice and Police Museum collection often possess an anonymous authorship informed by a bureaucratic and investigative imperative to document and capture forensic or physical evidence for later use in court these archival images also sit well with Sontag’s claim, that the urban photographer inevitably belongs to a flaneurial tradition, in which he participates, as “an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitring, stalking, cruising the urban inferno … [discovering] … the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes”. (Sontag 1979: 55). These crime photography images also remind us of another important tradition in the canon of western art photography, that of the “street photograph”: its interest in toughness, transitoriness, the multiplicity and estrangement of the surging life of the metropolis. This tradition attracted the talents of important photographers such as Eugene Atget at the end of the 19th century, Brassai and Bill Brandt from the 1930s and Joel Meyerowitz in the 1970s (who described one phase of his photographic career that was centred on the city street in classically forensic terms, as the search for the “all of it”).

The Crime Scene Image in the Age of Hyper-ReferentialityCrime scene photographs serve three purposes: they contribute an understanding of how a crime transpired, they define the geography of the crime scene for future reference and furnish proof on behalf of the prosecution that a crime actually took place. (Hargreaves: 1970: 211). Thus all crime scene photographs are filled with a stark and purposeful evidentiary imperative. Generally speaking - and this is an important consideration - crime scene photographs are not intended to seen, let alone appreciated beyond the detective’s office or the courtroom.

Newly liberated into the realms of publishing, art and museology however, crime scene photographs are now forced to operate in circulation with a vast commercial, creative and artistic image repertoire, resonating against images remembered from TV, film, advertising, book covers, and other images from the histories of art and photography. This new climate of cultural receptivity to the crime archive is also one of omnivorous and heterogeneous image consumption and a certain cynicism about the inherent meaning of any visual artefact that deals with the re-production of reality. In today’s image saturated culture a state of hyper-referentiality and de-valorising relativity prevails. Our visual sophistication and literacy ensures a relationship of constant comparison and cross-referencing to all manifestations of visually mediated culture we encounter and, as recent theorists have argued, this ongoing image bombardment corrodes and dismantles traditional truth hierarchies and creates a “proliferation of parasitic signs … which authorize all possible meanings without ever establishing one” (Bourdieu et all:1995: 142). Indeed, Barthes claims in Camera Lucida that ”what characterizes the so-called advanced societies is that they today consume images and no longer … beliefs”. (Barthes: 2000: 118-119).

Aesthetic Validation and Ethical Ambiguity

Traditionally speaking, there is nothing relative about a crime scene photo, which deals with a form of absolute certainty. The crime scene photograph is a document of sine qua non actuality, a part of a truth-telling project of modernism, at once, bureaucratic, scientistic and metaphysical. It is a thing that, more than any other type of photograph, “does not invent”, is “authentication itself”, and is “a certificate of presence”. But what happens when such an image – newly repositioned, re-presented and translated into the post-modern aesthetic realm - gets picked over by the rhetoric of “art”, and is assaulted, overlaid, freighted down by formalistic considerations of an artistic intentionality?

What happens when historic context recedes or is deliberately excluded from consideration by both presenter and viewer and the image is received only as a technically constructed pleasure giving visual artefact produced by the interplay of f stops, lighting, framing, saturated blacks and luminous whites? What happens when the crime scene becomes merely a composition, a referent, a stylistic quotation, disconnected from subject and cause? Will the authenticity of the image suffer, or is it enriched in new ways? Will this new kind of receptivity to the crime archive impede a respectful ethical awareness about its content? Does this new climate of exposure encourage a certain form of emotionally anaesthetized banality and voyeurism in an audience? Will the crime photograph’s purity and meaning be incrementally lost, even as its anonymous creators are recuperated from historical silence and praised for their visual prowess, their names celebrated amidst the nibbled canapés and sipped white wine of the gallery “opening”?

Such concerns and sensitivities are important but not easily resolved. Admittedly, my own response continually seesaws between a profound historical respect and a need to grasp the context of the terrible and at times sadly poignant content of these photos and a more poetic absorption into the play, suggestiveness and parabolic quality of the image itself. Perhaps too, the photographs themselves are sufficiently robust not to merit fears about reception in the aesthetic and ideas “market places”. For when dealing with photos of such startling quality and provocation, images that are so bristling with Barthesian punctum, canonical elevation will not automatically mean a diminution in power. The images themselves are too ferocious. Too tender. Too piteous. As Luc Sante say’s of the fraught act of re-presentation, in his introduction to his book of early 20th century crime photographs many of them grisly murders:

I am presenting them because of their terrible eloquence and their nagging silence. I cannot mitigate the act of disrespect that is implicit in the act of looking at them, but their power is too strong to ignore; they demand confrontation as death demands it. (Sante: 1992: xii).

The Optical Unconscious of the ArchiveIn one of his sermons against simulation and reproducibility Baudrillard talks of “surprising the real in order to immobilise it, suspending the real in the expiration of its double”. (Baudrillard, 1994:105). But to me, none of these crime archive photographs, all doubles of a vanished real, seem dead or immobilised. They rather continue to communicate and reveal: they are analogues to the behavioural and psychic destabilization that occurred during an important early phase of modernity, prime exemplars of Durkhiemian anomie. They especially remind us of Frankfurt school associate, Siegfried Kracauer’s claim, that within the early decades of the 20th century – man, surrounded by structures of glass and metal, movie theatres and racing automobiles - dwells in a condition of “disillusion” and “transcendental homelessness” (Macey: 2000: 217). And in this zone of excommunication from “reality”, confronted by the progress of capitalism and its varied cults of distraction life has become ruptured, contingent and fragile. Thus these crime archive photographs, like the pathologist’s charts at the foot of the hospital bed, also take the pulse of a deeply traumatised civilization that produced them. They ooze with the fraught atmospherics and compulsive energy of a young, bustling city, filled with a jagged excess of human emotion and its often desolating by-products: bizarre instances of communal breakdown, upsurges in casual and opportunistic crime, random accidents, symptomatic of the very speed with which modern life is now conducted.

The trauma that these images speak of is both collective and individual.

Souls are regularly unmasked by the prison photographer’s lens. A deep inner disturbance is visible in the way individuals stare listlessly back at the ruthlessly clicking box that enacts a double captivity, as if something is being broken inside, every time the shutter is snapped. In Regarding the Pain of Others Sontag makes the observation that a “beautiful photograph drains attention from the sobering subject and turns it toward the medium itself” (Sontag: 2002:77). But these images can be said to be beautiful in another sense; in their starkness, clarity and for the challenge to indifference they mount with their capacity to pierce, to wound, to make us feel.

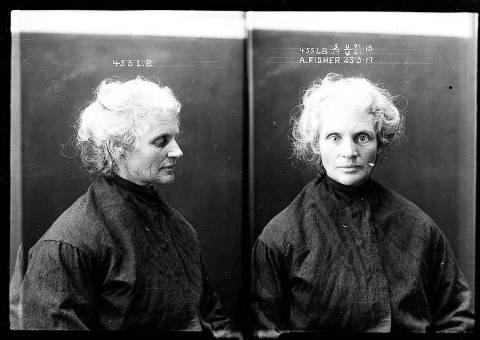

The collection contains its powerful ghosts … Annie Fisher, a Dickensian looking, glassy eyed, melancholy and perhaps not quite sane old woman … Yet research into the image revealed she was only 41 years old when the mug shot was taken in 1919 at Long Bay Female Reformatory, after she was arrested for stealing.

Every photograph within the Justice and Police Museum archive permits a return to an earlier reality. With this comes the revelation of a bygone vitality – restoring to us the self-absorbed energy, the hungry obsession with the instant and the complacency of the past - that challenges our right to call the contemporary moment, privileged, solid and authentic. In terms of the collection’s mug-shot portraiture in particular, we are forced to apprehend auras that are far from withered, in the Benjaminian sense. Instead we encounter police and prison portraits of forgotten offenders that crackle with electricity, uncannily alive with a passion, insolence and melancholy that stares back defiantly at us, from a frozen moment deep inside the past.

Walter Benjamin speaks of photography‘s “optical unconscious” that enables an image to store and release meanings “that were neither perceived by the photographer nor recognized by his peers”. (Wigoder: 2004: 7). The meanings these crime archive mug shots of the 1920s, 30s and 40s release are partly discovered within their mass accumulation of period detail. There is an enormous inventorying of clothing, hairstyles, shoes, ties, shirt collars, hats, the outward layers and wrappings human beings adopt to present themselves to the world. This external detail is combined with a capture of a more personal kind of information that exposes the ways in which the bureaucratically possessed and processed subject reacts to the machinery that seeks to ensnare that same subject in a strategy of objectification. We see this in the waves of louche defiance, cavalier indifference, disgruntled incomprehension and sad resignation emitted from the eyes to the camera’s lens.

Here among these thousands of mug-shots of largely forgotten individuals fixed in a silver emulsion imprint on glass we confront, “ghostly traces … the token presence of the dispersed relatives” (Sontag: 1979: 9). We also encounter many of those who typically get passed over and discounted within the broader historic record, those that social historian E.P. Thompson collectively designates “blind alley’s, lost causes, and losers of history”.

It is also worth noting images of death do not predominate in this collection, almost a pre-condition in other crime scene archives rescued from obscurity and brought to the public’s attention via books and exhibitions (Luc Sante’s Evidence, 1992, being the prime example produced by the forefather of this exercise). In fact murder scene documentation forms less than five percent of the total of this archive. The collection is extraordinarily diverse. Images filled with quirkiness, humour and oddity, photographs that often capture life’s unpredictable, haphazard and slapstick nature, sit in boxes beside invariably profound meditations on moral disaster and human vulnerability.

The images that make up the second half of this essay will reveal something of this diversity. They include accident scenes, urban streetscapes, murder scenes, evidence studies, mug shot portraits and photographs of missing persons. As the original case files are mostly lost, in many instances I cannot reveal what really happened or why. What I can offer is more meditative, my personal visual response – to the poetics, and teasing iconography present in these photographs - a reaction to the image as clue.

Forensic Photography Album

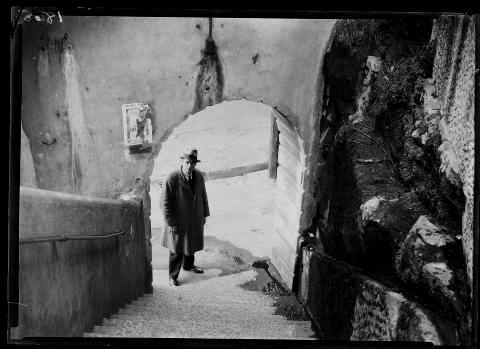

The first image I have chosen to dwell on depicts a 1930s detective framed by the arched entrance to the Argyle Cut, a dankly dripping passageway in Sydney’s The Rocks. An image filled with perplexed scrutiny and so noir, in framing, composition and depth of field, it could easily be a still from Carol Reed’s 1949 The Third Man, with its vertiginous mise en scene of maze-like tunnels, alleyways and sewers. The detective in this image seems to look out at us from his point in time to ours, asking the questions we still ask, what happened here and why? How can I explain?

In the forensic photographer’s visual reconstruction of the domestic crime scene of the inner city terrace, we always find a queasily ambiguous shot down the stairs … these staircases to doom inevitably herald bitter discoveries … Staircases are elliptical spaces. They provide a tension, a dot, dot, dot, a pause for the intake of breath, in the visual syntax of the crime scene, preparing us for the awful results of violent death always seeming to lurk at their bottom …

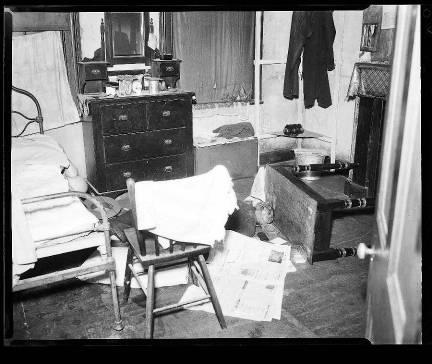

And quite often when we turn a corner at the bottom of the stairs we tend to discover a shabby room … in this case revealing the aftermath of a struggle, scattered newspapers, an overturned table, and a corpse.

Sometimes there is no corner to be turned and the stairs might be said to signal an imminent ascent of the human soul of the crime victim, lying at their foot.

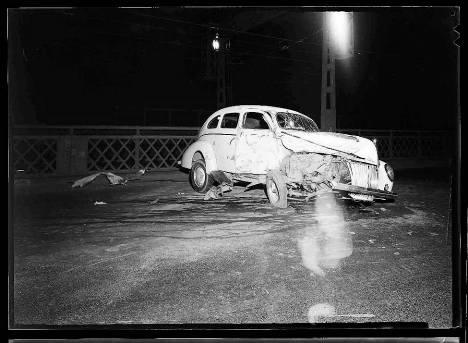

The collection holds extensive documentation of car accident scenes from the 20s and 30s. It is night that ushers in the existential zero point, Siegfried Kracauer’s “transcendental homelessness”. In darkness human frailty and vulnerability is amplified. This image depicts the aftermath of a high-speed collision on the harbour bridge, the pitiless flash, heightens the record of disastrous impact, the brutal starring of the windscreen suggests fatality.

Yet not all the car crash images in the collection are so ominous. This car has managed to straddle across the passageway into an underground toilet at Kings Cross in the 1940s. The image possesses an Arnold Odermatt-like quality of moral parable about the many drawbacks of disobedient machinery in which human beings tend to place too much trust.

Some collision shots even possess a sad humour. As when a van carrying perfect crumpets and muffins collides with a small truck.

Seen from another angle, a side view, close up, an almost amorous intensity of impact between the vehicles is suggested … as if the damage had arisen from a bout of overly impassioned kissing by the two machines.

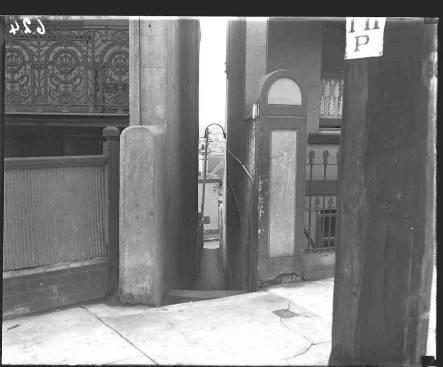

It is the shady alleys, the cracks between buildings where truly dangerous encounters tend to happen, those fissures in the streetscape where help is often too far away. This crime scene photo depicts the passage running down from Glenmore Rd, near Fiveways in Paddington, a mute but guilty space probed for evidence by the camera’s lens.

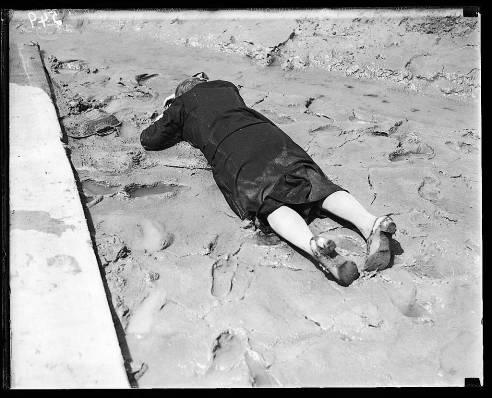

The scene of a sexual assault at the Domain baths in the 1930s: the legs of the innocent and unconnected sunbaker in the bottom right of the image, somehow suggestive of the malign activity that had gone on a while before.

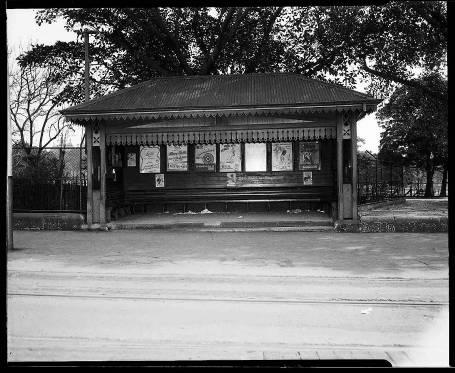

Another site of assault: a tram shelter on City Road: this image heightened by the presence of the groping arms of an over spreading fig in the background possesses an oddly malevolent atmosphere … despite its very blankness the image still seems to hum with the electricity of trauma and violation.

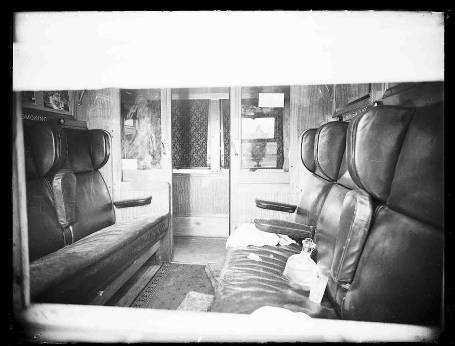

Something happened here. We don’t know what. An image of strangeness on a train: the parallel lines converging on a vanishing point filled with Hitchcockian paranoia.

And in the accompanying negative the illuminating burst of the photographer’s flash creates a pitiless cone of brightness over the crime scene for the hungry scrutiny of the detective’s eye; all of it revealing precisely nothing but suggesting everywhere the ominous and the unwelcome … the seats themselves taking on an unspeaking anthropomorphic presence.

A now vanished Sydney arcade, part damaged by fire, a detective lounges casually beneath a florist sign at the entrance to the arcade, the La Nita dress shop and in particular, its elegant deco mannequin, head turned coquettishly over its shoulder, remains serenely undisturbed by all the surrounding drama …

If images seem to unconsciously quote other images and the ideas connected to them this one did so for me … I thought of Walter Benjamin and his Paris Arcades project. Walter Benjamin on the photograph as a non-art object in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction and his judgement on Atget’s unsentimental c.1900 documentation of Paris streets, that Benjamin said had been photographed so that they resembled crime-scenes. Benjamin claimed it was with Atget that the modern clinically objective photographic gaze was born. This Sydney arcade image also made me think of Atget’s own love of shop windows and mannequins, with their frozen grimaces and disconcerting reflections. … his capture of an older urban world and its characters that was also on the point of vanishing … his picture of a prostitute in a shabby Parisian quarter … his fascination with commercial life, including the many strange emporiums that surrounded him … the disembodied but still eroticised corsets in his shop window … mysterious images heralded by Man Ray and Bernice Abbot as proto-surrealist masterpieces.

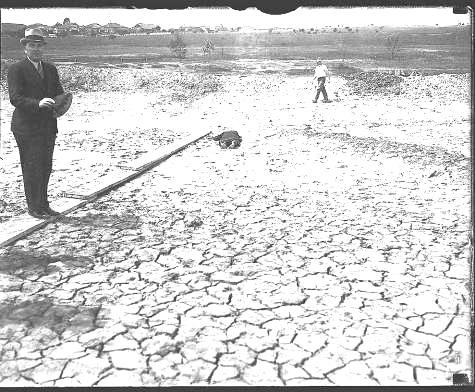

But in our own archive the stiff-mannequin seeming forms often turn out to be real people … In the outdoor crime scene a cinematic organization of space is apparent … An establishment shot sets the parameters of what will follow … then the camera begins to circle in from the periphery, to swoop, arc, hone … seeking to map the evidence from all angles … to solve the mystery of the forlorn female crime victim in the drained, mud caked dam.

The collection frequently contains moments of poetic mystery where the part stands for whole … whether it is a hat that is missing its owner ….

Or … a detached human mandible awaiting reconnection to other remains, if they should be found.

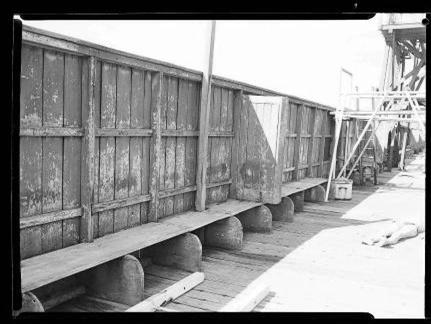

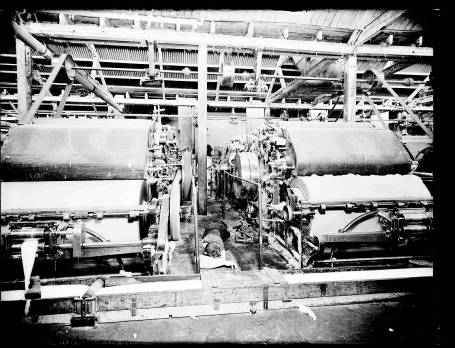

Accidents, injuries and deaths at work comprise another sub-genre within the collection – death can occur anywhere, even in the creaking wooden hold of an old ship …

While in this image, the frailty of the human body bracketed by the valley of heavy machinery, makes the loneliness of death more poignant.

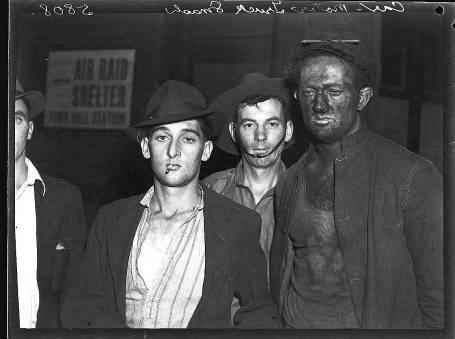

The collection is also filled with remarkable and startling examples of portraiture … three tough and insouciant characters in the vicinity of a war-time crash involving a coal truck …

A much softer and more lyrical image of interned aliens during World War 2. In Camera Lucida Roland Barthes reflects on a photograph of his deceased mother as a child in the following way ” … the Winter Garden Photograph, however pale, is for me the treasury of rays which emanated from my mother as a child, from her hair, her skin, her dress, her gaze, on that day “. This image, of interned aliens, that is also so pale, but sends out softness and radiance to the years beyond its taking, also represents for me a “treasury of rays”.

A startled old man, a Weegee-esque piece of flotsam blown into the police station from out of the night of a thousand crimes, to be wrapped in a blanket and photographed.

Detectives, filled with an Eliot Ness-like sobriety of purpose, self-satisfied hunters, beneath their visually captive prey behind them in glass.

WWII transvestites, butch hands hidden away from the camera, one scowls, the other laughs: the game temporarily up.

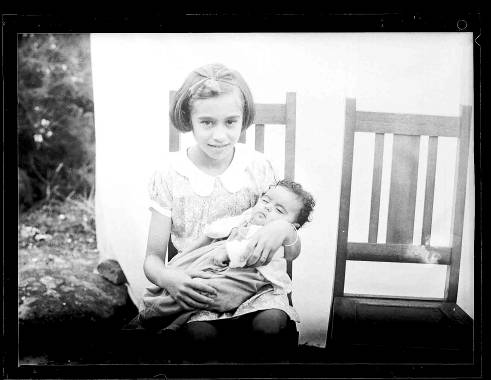

An unknown child found wandering at large … a poignant photograph of innocence that also conjures up sentimental period advertising images of children such as “bubbles” the soap girl.

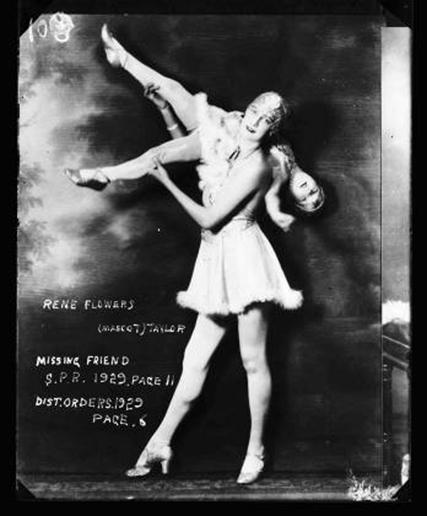

Now we call them missing persons in 1929 they were more warmly called “missing friends”. The showgirl jauntiness of the image adds to the pathos of an unexplained vanishing.

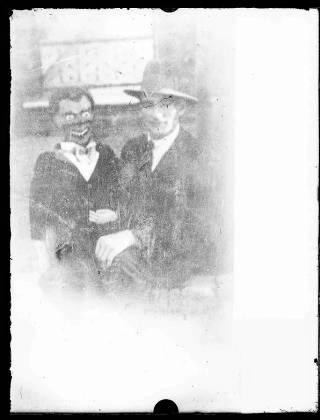

In this, my last photo, also a missing friend image the demonically grinning puppet definitely knows something is afoot and his malevolent cheerfulness increases our sense of premonition about the fate of his master.

Conclusion

Whatever framework of interpretation or analogy we use as a way in to these crime archive photographs they remain mysterious, resistant to ultimate definition. Their power often ushers the viewer into a zone of anti-rational feeling,a condition of pure contemplation in which speech can sometimes seem like a lessening and a betrayal. Despite this it still seems necessary to say something. To respond to the material is the scholar’s challenge and the curator’s duty. That this response may inevitably be diminished and questioned by the very image it sits beside must always be acknowledged. This piece of writing is an opportunity to think out loud about these and other problems; to affirm the power of the image and the insecurity of the word, the immersive, galvanic quality of the visual universe and the tenuousness of language in describing its effect.

Books

Barthes, R. (2000) Camera Lucida, London: Vintage.

Barth, M. (2000) WeeGee’s World, New York: Little Brown and Company

Baudrillard, J. (1994) Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan: University of Michagan Press

Benjamin, W. (1968) Illuminations, New York: Shocken Books

Bourdieu, P. (1990) Photography A Middle Brow Art, Oxford: Polity Press

Kracauer, S. (1995) The Mass Ornament: Wiemar Essays, Harvard: Harvard University Press

Macey, D. (2000) Dictionary of Critical Theory, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Sante, L. (1991) Evidence, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux

Sontag, S. (1979) On Photography, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Sontag, S. (2002) Regarding the Pain of Others, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Weegee (1973) Naked City, New York, Da Capo Press

Journal ArticlesHargreaves, E. (1970) “Scene of Crime” in Australian Police Journal, Vol 24, No 3, July. p.211

Wigoder , M. “History Begins at Home: Photography and Memory in the Writings of

Siegfried Kracauer and Roland Barthes” in History and Memory Vol 13, No 1 (2004) http://iupjournals.org/history/ham13-1wig.html

Images courtesy of Historic Houses Trust NSW and NSW Police Service.

Links

See also http://amol.org.au/craft/omjournal/volume4/volume4_index.asp Open Museum Journal, 2001, vol. 4 on the museology of the taboo.

http://www.geocities.com/cfpdlab/photos.htm Mike Byrd, contemporary crime-scene photography, Miami-Dade Police Department.