There has been considerable interest in these images since the 1970s. In 1982 Max Kelly published Faces of the Street, which gives a detailed historical analysis of photographs taken in William Street in 1916 prior to the resumption of ninety-four properties on its south side. Other images from the Demolition Books have been scrutinized in Kelly’s Plague Sydney and have been included in general collections of photographs and work on the history of photography (Russell 1975, Willis, 1988). In a broader context interest in historical images such as these has also grown. They have been aestheticised for their formal, stylistic qualities; popular history has constructed them as nostalgic remnants of a lost past; they have been scrutinized as artefacts both symptomatic of technological modernism and suggestive of the nature of modern urban subjectivity. In this essay I will follow Kelly in looking at them as historical texts, for the specific information they carry about their time and place. I will begin by discussing the historical context, and the cross-currents of discourse which both impelled and gave meaning to the process of urban renewal, in furtherance of which these photographs were made. I will then look at a selection of the photographs as carriers of incidental, unintended content. In doing so my response is personal and impressionistic rather than systematic and empirical, for as well as bearing clues about the lost world of the past, these images are both beautiful and semiotically rich, and imaginative engagement with them is difficult to resist.

It is easy to get lost in these pictures, to be drawn into the absorbing historical microcosm that they open up. But when we notionally zoom out to take in the photographer, his masters on the City Council, and their masters in the world of business and commerce, we see that the subjects so vividly present were caught up in currents more powerful than they knew. The residential suburbs here recorded – Pyrmont, East Sydney, Surry Hills, Redfern, Ultimo, Chippendale and Miller's Point – were densely populated neighbourhoods where even dilapidated houses were in great demand because of their proximity to places of mass employment like the wharves and Darling Harbour goods yard. But these places were also valuable to business interests, as warehouse sites for example. And as Fitzgerald has shown, the needs and preferences of residents counted for little when measured against the more privileged imperatives of an expanding industrial and commercial sector (Fitzgerald 1987:65). Within the space of a few decades a large part of the city's housing stock was demolished. Multi-storey offices and warehouses replaced rows of terrace houses; Oxford, William, Elizabeth and George Streets, which intersected the inner suburbs, were widened and straightened to ease the flow of traffic in and out of the city; harbourside houses were resumed for the construction of the harbour bridge linking Sydney's northern and southern shores. Such developments would entirely change the face of the inner-suburbs.

We cannot doubt that the re-shaping of the city, in the interests of which these images were made, represented the working out of ideology. Space as a social fact is always political and the control of its use is always strategic. As Habermas reminds us, the public sphere is inevitably shaped in the interests of the bourgeoisie, and clearly bears the hallmarks of its rationalist and commercial preferences. The discourse of urban renewal invoked the ideology of progress to characterize the changes being wrought on the city landscape. The vocabulary of progressivism emphasized continuous improvement in all aspects of life for all the city’s inhabitants. But the rhetoric both masked and legitimated specific processes of modernization which required the re-modelling of city environs into a specialized commercial district. Changes which aligned with the needs of business interests to reclaim residential spaces were represented in general terms as the public good, expressed in terms of expansion and improvement. A complex of discourses was at work in the process which can be schematized as a series of dichotomies.

Urbanism vs. Suburbanism

The typification of the demolition process as “slum clearance” drew on anti-urban discourses, still powerful in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They had found expression in Victorian exposes of the dark side of urban life, of the “Lights and Shadows” variety. Sydney lent itself to such representations. As was often observed by visitors, it was remarkably ancient looking for a comparatively young city. Its narrow crooked streets and antique buildings were likened to those of London, the benchmark, since Dickens and Mayhew, for the sinister side city life. According to one of the numerous City Council functionaries who seemed able so freely to enter and scrutinize the homes of lower-class people, Sydney’s slums were “in every degree the peers of the slums of London …as centres of dirt, vice, crime and ugliness” (Boyce 1913:12).

Unspoken fears about the city have been analysed by Briggs who distinguished between “romantic fear” of the city and “rational fear” of the consequences of specific urban problems such as overcrowding and disease outbreaks (Briggs 1965:85). In the case of London, detailed and systematic study had, by late in the nineteenth century, generated a significant base of statistics for use in judging such matters. In Sydney on the other hand, archetypal fears which welled up from the social imaginary were not always easy to disentangle from well-founded concern. Very little empirical data existed outside the minimal figures compiled by the government statistician (Fitzgerald 1987:198), and decisions about municipal reform were commonly based not on evidence but on unfounded and often alarmist assertions.

Denigration of the city was accompanied by the promotion of suburban living as an ideal, a rus in urbe. In the wake of Federation new suburbs with parks and wide streets of detached houses with gardens, began to encircle Sydney. Not only were they represented as environmentally salubrious, they also came to be associated with cultural and racial superiority (Ashton 2000:42). In contrast the old inner-suburbs and their terrace houses were seen as slumlike, embodying the dark, dangerous, ancient life of the city (see Ludlow 1998). Implicit in the demolition process was an expectation that the residents of condemned buildings would be forced out to find better housing in the suburbs. A Council Inspector was incredulous that people would live by choice in these “closely-huddled hides” paying for them “rents which would house them decently in the suburbs” (Mayne 1990:34). Not all reformers held such black and white views. Canon Boyce, the Anglican Archdeacon of Sydney, and an active social reformer, could see things from the residents' perspective:

There are many persons who find it most convenient to live near their work. Indeed must do so, and why should they not be considered? Why too depopulate the city? Much as I can favour the suburbs for ordinary residential purposes, that idea can be carried too far (Boyce 1913:34).

Idealists formulated another, less conservative dichotomy as Utopia vs. Dystopia. In an idealistic projection of the future they envisioned a perfect city accommodating a perfectible population. Louis Esson, a left-wing poet and playwright wrote:

Nature intended that Sydney, the essential Sydney, should be the Queen of all modern cities. She must be created anew. There should be wide, tree embowered streets and avenues where now twist slums and alleys. There should be great squares and marble columns and cool porticoes and fountains playing. There should be arcades, splendid pieces of street architecture. Noble boulevards should run all round the harbour. Up any hill we should see bright white houses with sculptured balconies; down any hill the dazzling blue waters…Sydney must be the capitol of an earthly paradise (Kelly 1982:1).

The Future vs The Past

Discourses which invoked the ethos of modernity constituted another legitimizing framework for the demolition process. It seemed obvious that eradication of the decaying remnants of the past was necessary to make way for a better, more modern future. The Sydney Morning Herald described parts of inner Sydney as exhibiting the “very worst conditions which are usually only associated with mediaeval cities of heavy antiquity” (Boyce 1913:6). Associations with the convict past which haunted the whole of Australian culture were unavoidable. The founding citizenry of Sydney had been the rejects of British society, its petty criminals, its poor, its underworld denizens, its lumpenproletariat. But by the beginning of the twentieth century “The System” was long past. Anti-transportation forces had long since won the day and civic leaders were turning their efforts to building a modern, progressive city. Unremitting boosterism was the prevailing sentiment. One popular verse urged:

Look ahead and not behind us! Look to what is sunny, bright –

Look into our glorious future, not into our shadowed night (Hughes 1987:597).

In the face of persisting anxiety about the convict “stain” a strong mechanism of denial developed in the realm of the social imaginary which sought to repress the memory of the city's penal origins. The destruction of Sydney’s pre-modern built environment was a step towards erasing the material remnants of its shameful human history. Those hewn stone houses, narrow and verminous and dark, had been built by convicts, and therefore, might not some of the old convict tradition have soaked into them?

Health vs Morbidity

The discourse of public health was often used to rationalize Council's urban renewal activities. Environmental factors such as lack of adequate sanitation, the narrowness of streets and lanes, dilapidated structures, overcrowded living conditions and damp and low situations, were all cited as threats to public hygiene. Outbreaks of contagious disease confirmed the notion and added weight to calls for slum clearance; resumption activity peaked during the smallpox epidemic of 1881, and again during the outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900 (Mayne 1990:104). Although the germ theory and asepsis were well known by the turn of the century, many in the medical profession and probably most of those influential in urban renewal continued to subscribe to the miasmatic theory, based on the notion that disease was carried by noxious exhalations detectable as smells. The stench of poorly drained and aired houses was identified as symptomatic of the presence of morbidity. As a charity worker from the Sydney City Mission declared “The smell of the places was enough to create disease” (Boyce 1913:13).

Reformers like Canon Boyce advocated putting bathrooms in all rented houses (Boyce 1913:3) but his was a lone voice. Official consensus favoured demolishing the houses and encouraging people to move out of the city. The vocabulary of pollution used by Council Inspectors to describe sub-standard housing stock was extended, quite explicitly, to the occupants who were typified as “worthless people” (NSW Intoxicating Drink Inquiry 1887:22), “the unhygienic products” (Boyce 1913:5) of city life and so on. Inner-city denizens were characterized as stunted, weedy, mis-shapen by the deforming influence of their unhealthy surroundings. The open spaces of the suburbs were advocated as a more wholesome and health-giving environment. Resistance to moving was interpreted as an obstinate clinging to vice and squalor, proof of moral degeneracy.

Morality vs Immorality

According to Thomas Sapsford, the City building surveyor, the intention of the demolitions was as much “to …prevent immorality” as “to preserve the health of the Citizens and beautify the City” (Mayne 1990:57). He maintained that “if dens are…permitted to exist for the accommodation of infamy in the very heart of the City good health cannot possibly prevail”. The conditions of the built environment were thus seen to both reflect and shape the character of its inhabitants. Another commentator claimed

As long as we have such streets as are to be found in Woolloomooloo, Surry Hills and, in fact, right throughout the city and near suburbs, we shall be faced with a sickly, immoral and degenerate section of citizens' (Yarrington 1914:9).

On this point Canon Boyce was in agreement when he declared “immorality and crowded areas always go hand in hand” (Boyce 1913:2). On a tour of Chippendale he made in the company of a Sun journalist and photographer, he saw “lazy men and…slatternly women – many obviously base women – [s]quatting down in doorways…leaning over balconies half-clothed” (Boyce 1913:11). He regretted that the respectable poor were forced to live “side by side with …the thieves and lowest prostitutes of the city”. Finch has shown how in the late nineteenth century the discursive category of the working class was constructed around a set of moral criteria, which encompassed living conditions (Finch 1993). Specifically the failure to demarcate special rooms for sleeping, to privatise the conjugal bed, and to allocate separate beds to each family member were condemned. “When y’r married daughter and her husband and four children’s livin’ with you, there’s no use in bein’ fussy”, says Mrs Blore from Kylie Tennant's Foveaux (Tennant 1939:127). The implication that promiscuous sleeping arrangements resulted in unsanctioned sexual relations, notably incest, was strong, reinforcing constructions of poor inner-city residents as an immoral and degenerate class.

Whites vs Non-whites

In the first decade of the twentieth century race anxiety gripped the nation. In such a climate racial cleansing came to be invoked as yet another rationale for urban renewal, and Sydney’s large Chinese population were targeted. The 1901 Inquiry into Chinese Gambling found that charges of enslaving white women and wholesale gambling and opium smoking which had been levelled at the community were unfounded, and that the Chinese were in general law-abiding citizens. The Inquiry's evidence notwithstanding, Wexford Street, occupied mainly by Chinese businesses and residents, was resumed for widening in 1906. It was estimated that 724 people were displaced when their houses were demolished to make way for the new Wentworth Avenue. When Canon Boyce toured the area in 1910 he was able to report “The Chinamen have mostly gone since Wexford Street was resumed”. But racial homogeneity had still not been achieved for “doors and balconies swarm with Indians, negroes, half-castes [and] half-breeds” (Boyce 1913:11).

The Images

Within such webs of discourse the photographs simultaneously manifest the historical facts of the everyday, lived experience of the subjects. They disclose the streets as familiar spaces, informal settings for the enactment of everyday rites and practices. The glimpses they offer us are rare. The images of the human subjects are especially unusual for two reasons. Firstly, this class of people, the lower-class, the humble, the poor, however one chooses to label them, were not often photographed, the cost of studio portraits being beyond their means. Some may never have been recorded by a camera except on these occasions. Many would only have been photographed as subjects of institutional life in school, or at a rite de passage like a wedding.

Secondly, although the photographs were planned and premeditated, the subjects are not, as was the convention of the period, organized into a self-conscious composition. They are captured as it were in a fluid moment, in situations and involved in a quotidian round of activities that were not normally thought worthy of recording - playing, gossiping, child-minding, passing the time of day. Because their presence is accidental it is also random and unconstrained. Some seem oblivious of the camera. Others are quite aware. They demand the attention of the photographer. They pose. They mug. They act the goat. They squeeze up together to fit in frame.

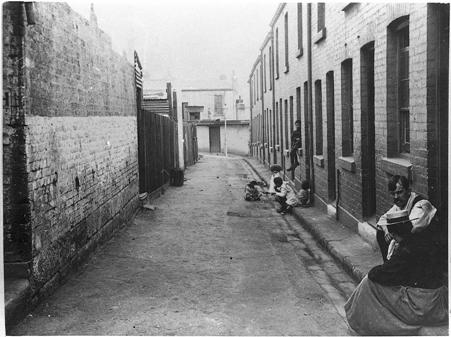

The subjects in these images are women and children, a home-based, pedestrian population whose spatial reach was circumscribed. While the men were away at work or in search of work, or at the pub, they stayed within the realm of the home, the street, and those twin institutions of lower-class neighbourhoods – the pub and the corner shop. The street, which in other contexts was part of the public sphere, was annexed for their daytime use as an extension of cramped domestic quarters. Goffmann, in his schema of social performativity, distinguished between the back region where the public face is prepared, and the front region, where the subject presented him or herself in a public role (Goffmann 1959). These images tell us that the daytime residential streets were used as another back region, a continuation of the domestic sphere. Children played mostly in the street. As one eyewitness noted “The doorstep was the favourite lounge; or the kerb… The doors stand open wide; and in some streets they seem to make quite free of each other’s houses” (Boyce 1913:11). The women wore aprons, were hatless, the children often uncombed. The people were merely extrinsic objects in these pictures, obscuring the intended subject, and as such had implicit licence to forego the preparations, the disciplining of the self that public appearance normally required.

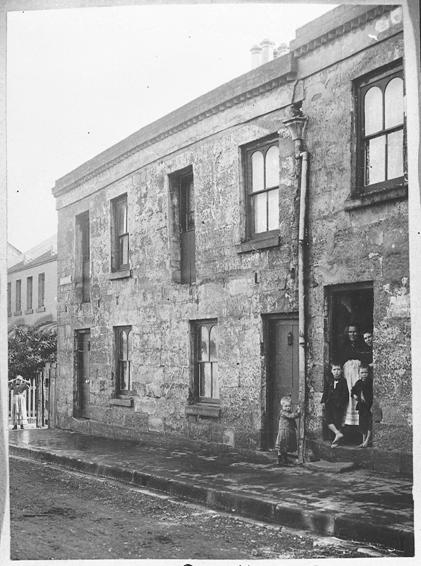

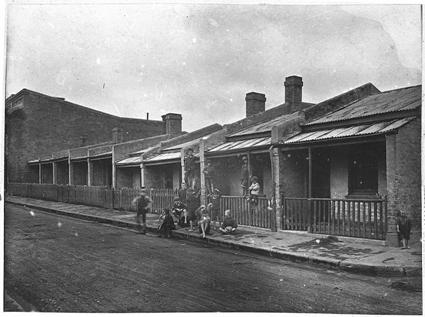

c.1900. Terraces, Wattle Street Pyrmont. This photograph and the one which follows were taken soon after bubonic plague had broken out in Sydney. Cases of plague had been reported not far from this neighbourhood. The family, perhaps mother, grandmother and children, are drawn to their front door to watch the photographer at work. A curious neighbour down the street has also come out for a look.

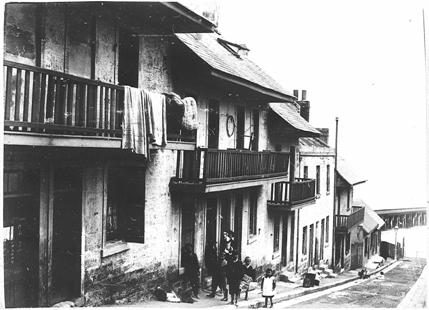

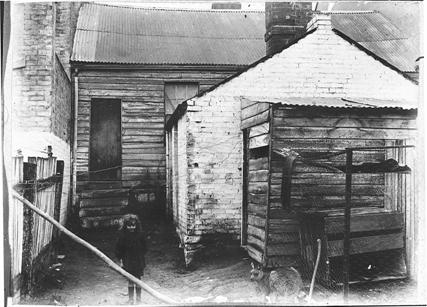

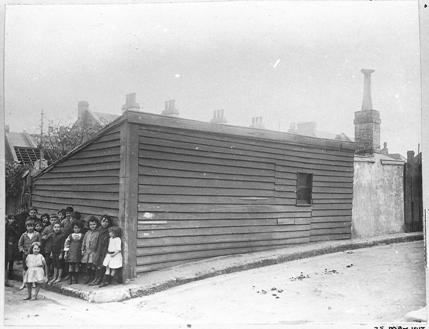

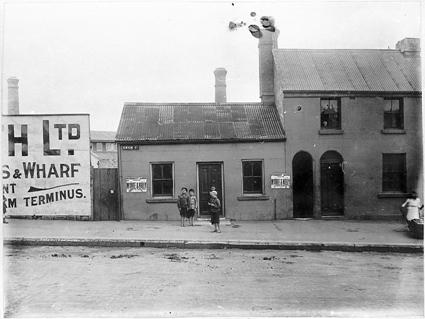

c.1900. These houses are in Athlone Place Pyrmont, which no longer exists. Some 400 dwellings and a maze of tiny lanes in this area were cleared by Council. The extremely short hair of the child in the foreground suggests that its head had been recently shaved, a hygienic measure against headlice.

May 2nd 1902. A corner shop in John Street, Surry Hills, in the vicinity of the notorious Frog Hollow. This appears to be a sweet shop, selling soft drinks, ice-cream, milk and lollies, a business which required less outlay for stock than a grocer's. Aside from home-based work such as sewing or washing, small-scale petit bourgeois enterprise, like Mrs Giblin's shop, were among the few earning options open to women.

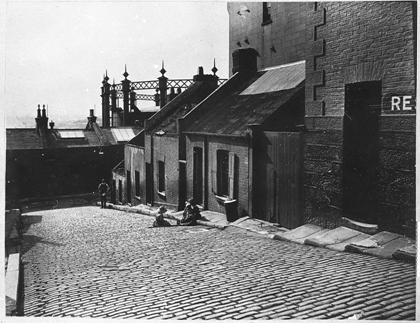

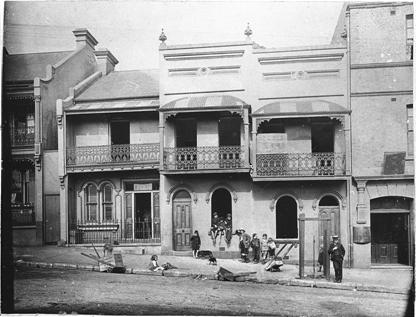

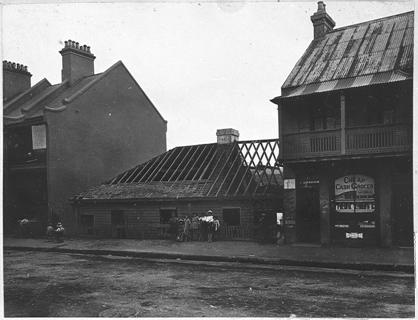

April 1st 1901. Clyde Street, Miller’s Point, built in the 1830s and resumed and demolished by the Sydney Harbour Trust soon after this photograph was taken.

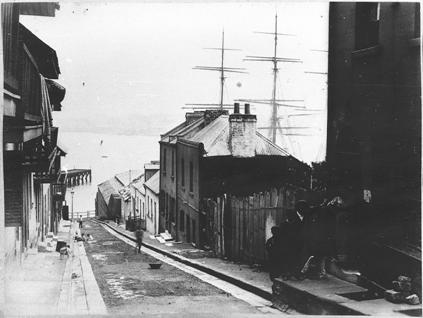

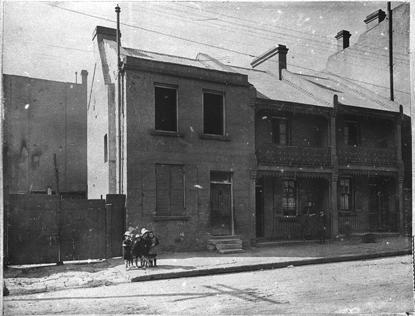

April 1st 1901, Clyde Street, facing towards the harbour. Some, but not all the front steps have been whitewashed, a marker of respectability.

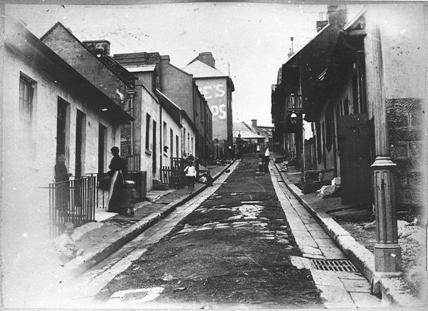

April 1st 1901. Clyde Street looking upwards from the harbour. Part of an advertisement for Wolfe’s Schnapps can be seen on the building in the background. This particular brand of liquor was constructed as medicinal, intended to assure women they could buy it without compromising respectability. “Rheumatics, gout and dropsy, and other fleshly ills, WOLFE’S SCHNAPPS turns ‘topsy-turvy’, and saves your doctor’s bills”, went the slogan.

1909-1913. Houses in Gas Lane, Miller’s Point. The street is paved with wood blocks. The children sitting in the street appear to be reading. The man in the background is holding what looks like a sheet of paper; perhaps he is assisting the photographer.

1909-1913. Small scale shops in Clarence Street including the Ah Sam Chinese laundry. Ah Sam has seen the writing on the wall. His shop has a “For Sale” notice.

June 11th 1901. Campbell Street Surry Hills. The tame kangaroo in this inner urban setting undercuts the stereotyped images of native fauna surrounded by gum trees and open plains which were appearing in various popular genres in this post-Federation period.

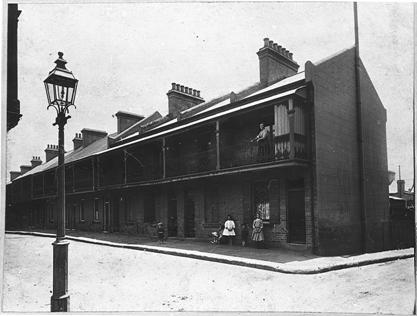

1909-1913. Terraces, O’Connor and Balfour Street Chippendale. The girls are neatly and respectably dressed, and the open shutters on the corner house reveal lace curtains, a genteel touch. The ritual of the upkeep of a parlour was regarded with favour by official visitors, approved as a plucky attempt to keep up appearances in the face of poverty.

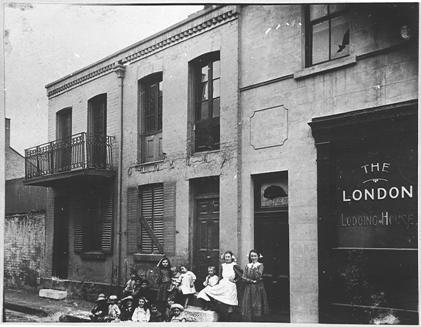

1909-1913. Houses and a lodging house in Kensington Street Chippendale. These were probably resumed to make way for the brewery which now occupies one side of Kensington Street. A group of children stand on the footpath outside the corner house, the respectable with the non-respectable, the booted, clean-faced, combed and starched with the grubby, shock-haired and barefoot. They form two rows which suggests the photographer, or perhaps one of the older children, may have arranged them thus. The London lodging house is vacant, to judge from the broken window glass. There were numerous such lodging houses throughout the inner city area, catering mainly for single working men who were assumed not to be domestically viable without the services of a woman.

1909-1913. Myrtle Street Chippendale. A group of boys, most barefoot, one sitting in a handcart, pose and caper about for the camera. A small lone boy peeps from round the corner, too young or maybe too timid to join the others.

May 25th 1917. Palmer Lane Darlinghurst. A group of children squeeze together against the side wall, perhaps at the direction of the photographer to give him an unimpeded view of the back of the building.

1909-1913. Terrace houses, Foveaux Street, Surry Hills. A workman is just visible inside the door of the house on the left. The presence of the three hand carts suggests that the children have come to pick up salvage, firewood perhaps, which was at a premium in the inner city.

1909-1913. Wilmott Street, City South. These small children seem to cling together shyly. The blur on the right is probably a moving child, the blur behind it probably another specimen of the ubiquitous handcart, which served for both haulage and recreation.

c.1913, Union Street, Pyrmont. A child looks from a first floor window. Posters for McGee and Kelly, candidates in the ward election are pasted on the wall behind the boys.

c.1913. Irving Street, Chippendale. Also near the present brewery site.

1916. Riley Street, Surry Hills. The handcarts and their child drivers are at the ready. The cart on the right and the bag on the ground already contain pieces of wooden palings.

1909-1913. Kippax Street, Surry Hills. This old weatherboard house in the process of being demolished is set below the roadway, a position thought to be particularly unhealthy.

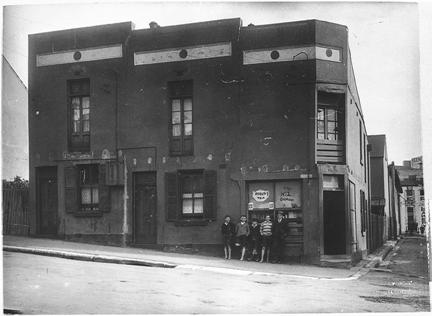

June 15th 1928. Crown Street, Darlinghurst. The teapot in the ad for Robur Tea on the window is an emblem of Sydney’s number one vice. The Temperance movement characterised Sydney as a drunken city, and exerted political pressure which resulted in the closure of many pubs and restrictions on the sale of liquor. But statistics indicate that the people of Sydney drank no more than their counterparts in London, and considerably less than those of most Irish cities (NSW Intoxicating Drink Inquiry 1887:22). However they did distinguish themselves when it came to tea-drinking, managing to consume more tea per capita than any other nation in the world except China (Dingle 1980).

June 19th 1916. Gladstone Hotel, East Sydney. The sign on the house reads “French Laundry”. What specific refinement on ordinary laundry French laundry offered remains a mystery. Or perhaps the phrase was a euphemism for more personal services. Such signs remind us of the importance of home-based laundering work for women with children.

c.1906. Stephen Street, demolished as part of the Wexford Street (now Wentworth Avenue) resumptions. A man and a woman sit on a doorstep conversing. Most of these images have a rather benign ambience, which makes me think that the subjects were unaware of the photographer's purpose. This one is an exception. The man glares at the camera. The woman looks as though she may be averting her face.

The subjects in these pictures had little or no influence over the political processes which were transforming the localities where they lived. They were not meant to be in these official images whose purpose was to facilitate destruction, yet nonetheless they are vividly present, playing out what Certeau calls the drama of alienation. The subtle, insistent activities of their daily lives persisted in undeclared opposition to the triumphalist rhetoric of urban renewal. Their presence represents an affirmation of the everyday, an assertion of its constancy, its continuity, in the face of larger, more powerful waves of circumstance. I can think of no more fitting conclusion than to quote from Lefebvre: “[W]here is genuine reality to be found? Where do genuine changes take place? In the unmysterious depths of everyday life”.

Books

Boyce, FB (1913) The Campaign for the Abolition of the Slums in Sydney, Sydney, William Andrews (ML 208/B)

Briggs, Asa (1965) Victorian Cities, Berkeley, University of California Press

Finch, Lynette (1993) The Classing Gaze: Sexuality, Class and Surveillance, Sydney, Allen & Unwin

Goffman, Erving (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Harmondsworth, Penguin

Hughes, Robert (1987) The Fatal Shore: a History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia 1787-1868, London, Pan

Kelly, Max (1982) Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, Sydney, Doak Press

Kelly, Max (1981) Plague Sydney: a Photographic Introduction to a Hidden Sydney, 1900, Sydney, Doak Press

Russell, Eric (1975), Victorian and Edwardian Sydney from Old Photographs, Sydney, Ferguson

Willis, Anne-Marie (1988) Picturing Australia: a History of Photography, Sydney, Angus & Robertson

Fitzgerald, Shirley (1987), Rising Damp: Sydney 1870-90, Melbourne, Oxford University Press

Mayne, Alan (1990), Representing the Slum: Popular Journalism in a Late Nineteenth Century City, Melbourne, University of Melbourne History Department

NSW Intoxicating Drink Inquiry Commission 1886-87. Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, 5 Oct 1887, Sydney, Government Printer

Tennant, Kylie (1939), Foveaux, Sydney, Angus & Robertson

Yarrington, Rev SD (1914), Darkest Sydney, Sydney [no pub. Details] (ML331.84/Y)

Journal articles

Ashton, Paul, “’Our Splendid Isolation’: Reactions to Modernism in Sydney’s Northern Suburbs”, UTS Review 6:1, May 2000, pp41-50.

Dingle, Anthony (1980) “’The Truly Magnificent Thirst’: an Historical Survey of Australian Drinking Habits”, Australian Historical Studies 19:1980 pp227-249.

Ludlow, Christa (1998) “The Reader Investigates: Images of Crime in the Colonial City”, Public History Review 7 pp43-56.

Links

For City of Sydney “Demolition Books 1900-1949” go to: http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/AboutSydney/HistoryAndArchives/Archives/InformationLeaflets/DemolitionPhotographs1900-1949.asp

Follow link to ArchivePix