Introduction

Architecture and store design are increasingly significant to fashion brands as powerful media for the expression of brand image and story (Riewold 2002). While this relationship is not entirely new, fashion brands such as Fiorucci, Pierre Cardin and Biba have augmented their image using store design since the 1960s (Mores 2006). Battista (2010) identifies that the overtly collaborative relationships between fashion and architecture are embryonic and will be an area of growth for practitioners and academics alike. As the boundaries between fashion, retail, art and architecture continue to blur, architects have actively sought collaboration with fashion brands, and vice versa (Bingham 2005). Contemporary collaborations have developed beyond the design of spaces for selling apparel, extending now to the synergetic creation of products and cultural experiences which are visually spectacular, creatively influential and commercially significant. Meanwhile, hybrid exhibitions in New York (2006) and London (2009) have stimulated a dialogue for exploring the relationships between the disciplines (Menkes 2009). The paper provides an insight into this phenomenon by considering the nature and characteristics of contemporary instances to identify the key drivers of fashion and architecture collaborations.

The Oxford English Dictionary (2010 :106) defines 'collaboration' as "work jointly", whilst Huxam (1996: 3) refers to it as "working in association with others for some form of mutual benefit". Key to these definitions is the implication of parity between partners. De Cherntony and McDonald (2006) state that collaboration may be creative in nature as it offers participants the potential to add value and enhance brand equity. Collaboration also has differing meanings across sectors, from industry to education and the arts, and is often referred to in literature as strategic alliances, joint-ventures and co-branding (Huxam 1996). Instances of collaboration are categorised with respect to a/symmetrical and horizontal/vertical typologies; where symmetrical collaboration implies equality between partners, and asymmetrical collaboration occurs when one brand is more dominant than the other (Uggla 2004). Horizontal collaboration describes partners at the same level or sector working together, while vertical collaboration implies a relationship with partners from a different market level or sector (Chasser & Wolfe 2010). Applying these typologies to instances of fashion designer-architect collaboration, it appears that the majority are symmetrical and vertical in nature. Such collaborators are working across sectors in a relationship that broadly involves equal investment of financial, creative and material resources.

The following section of the paper elaborates on instances of fashion designer-architect collaboration and provides an exploration of the fashion brands involved in such activity.

FORM

Three main sources of collaboration have been identified: stores; products; and 'third space'.

Store Collaborations

The most obvious, and historically the most popular type of collaboration between architect and fashion designer has been store design (Battissta 2010; Tungate 2009). In early twentieth century France, Couture fashion designer Madeleine Vionnet worked with architect Ferdinand Chanut to create a 'Temple of Fashion' on Avenue Montaigne in Paris (Golbin 2009). In Milan, in 1967, Elio Fiorucci collaborated with architects Ettore Sottsass, Andrea Branzi and Franco Marabelli to create the designer's 'personal inclusive vision of fashion' (Mores 2006). In the last decade the flagship store has become the major focus of fashion-architect collaborations (Reynolds et al 2008). Flagship stores are characterised as being larger than average, in an exclusive location, at the top of the product distribution hierarchy and being exceptionally well designed (Moore and Docherty 2007). The level of investment and planning necessary in these projects imply a longer-term and more involved relationship than evident in alternative fashion designer-architect collaborations. The collaboration between architect John Pawson and designer Calvin Klein for a Fifth Avenue flagship in 1996 is noted as significant in providing momentum to the evolution of these relationships (Barreneche 2005). Concurrently, the term 'starchitect' was coined by journalists to describe architects who attracted celebrity status partly due to their work on behalf of high profile fashion brands (Chow 2003) - examples include Frank Gehry ( Issey Miyake), Future Systems (Marni) and Renzo Piano (Hermes). One of the most prolific 'starchitects' is New York based Peter Marino, responsible for flagships with Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Fendi and Dior. Marino's ability to capture the essence of the brand whilst bringing new perspectives has allowed him to become one of the pre-eminent fashion flagship architects (Jana 2007). His most recent fashion project, the London Louis Vuitton 'Maison' (Bond Street), exemplifies his status, where the store integrates LV's heritage with his contemporary design credentials in an innovative environment (WGSN 2010).

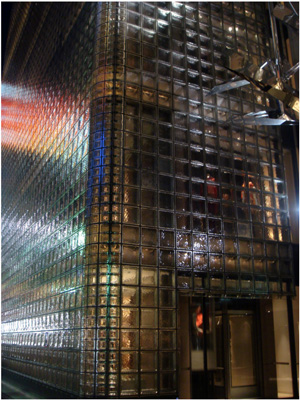

Figure 1: Louis Vuitton 'Maison'. Bond Street, London. Architect: Peter Marino (Exterior View)

Figure 2: Hermes 'Maison Hermes'. Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Architect: Renzo Piano (Exterior View)

Figure 3: Hermes 'Maison Hermes'. Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Architect: Renzo Piano (Exterior View)

Prada has become equally synonymous with innovative products and avant-guarde design and materials, as with its store designs which have set the standard for luxury fashion flagships (Barreneche 2005). Labelled 'epicentres', Prada created three highly conceptual and technologically advanced stores: New York (2001); Tokyo (2003); and Los Angeles (2004). Designed in partnership with Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron, each epicentre has a unique design while sharing a conceptual theme of integrating smart technologies such as RFID (Radio-frequency identification), 'intelligent' changing rooms and interactive screens within distinctive, multi-utility environments (Moore and Docherty 2007; Prada et al 2010). The distinguishing characteristic of the epicentres is their innovative and experimental role in fusing the commercial purpose of a retail space with a creative and cultural purpose. The result is that each epicentre is a destination as much for lovers of design and architecture as fashion and shopping (Curtis and Watson 2010).

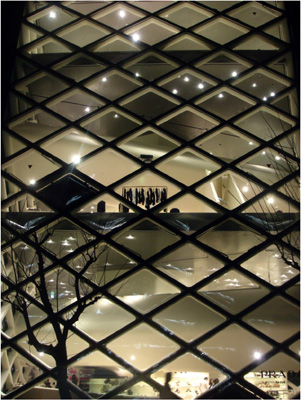

Figure 4: Prada 'Epicentre: Tokyo'. Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Architects: Herzog & de Meuron (Interior view)

Figure 5: Prada 'Epicentre: Tokyo'. Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Architects: Herzog & de Meuron (Interior view)

Figure 6: Prada 'Epicentre: Tokyo'. Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Architects: Herzog & de Meuron (Detail view)

Alternatively, the temporary aspect of store collaborations must also be acknowledged, and is evident in visual merchandising strategy of fashion brands. Laub (2010) noted the growing number of fashion designers collaborating with architects and product designers at the Milan Furniture Fair to create installations and collections within flagship stores and curated in window displays. Similarly, July 2010 saw various London-based architects collaborate with Regent Street fashion stores to produce visual displays celebrating London's Festival of Architecture (Dickenson 2010).

Product Collaborations

Fashion designers have often found inspiration in architecture; some, such as Hussein Chalayan, Martin Margiela and Issey Miyake have had collections described in architectural terms such as 'structural' and 'engineered' (Miles 2009; Almeida 2009). However, specific collaborations between fashion designers and architects developing new products have become evident only in the last five years. Zaha Hadid, another 'starchitect', is recognized for her dynamically fluid architecture which is particularly well-suited to apparel and accessory design experimentation (Almeida 2009). Hadid has worked on a large number of fashion product collaborations, including Louis Vuitton (2006), Melissa (2008), Swarovski (2009), and Lacoste (2009). Iconic flip flop brand Havianas regularly collaborates with artists, designers and architects, using the resulting products as the inspiration for integrating window, point of sale and advertisement design (Carr 2007). Other successful partnerships include G-Star with Mark Newson, Ron Arad with Notify Jeans and Frank Gehry with Tiffany. The inspiration arising from such relationships may be reciprocal; for example, recent advances in intelligent knitting have promoted the role of textiles in architecture with fabrics which sense and react to their surroundings (Mosse 2010).

Third Space Collaborations

A third space is defined as "somewhere which is not work or home but a comfortable space to browse, relax and meet people" (Mikunda 2004:11). This definition implies a space with a social function, which in the context of this application means it assumes an experiential hedonic role to consumers, as there is no sales function. Three notable projects within this typology include Chanel, Prada and Calvin Klein. During February 2008 in Hong Kong, Chanel launched 'Mobile Art', a collaboration integrating art, fashion and architecture within a futuristic structure designed by the aforementioned Zaha Hadid (Wu 2008). The design of the structure's shell shaped white exterior was praised for capturing the timeless classic essence of the brand whilst also emphasising its directional nature (Seno 2008). The exhibition was met with critical acclaim and was intended to tour major fashion capitals such as New York, Moscow, Tokyo, London and Paris, however due to the recession the project was suspended after New York (Barnett 2008).

In April 2009, Prada opened a transformable arts installation in Seoul. Coined the 'Prada Transformer', this architectural design combines four different structures and was designed by longstanding collaborator Rem Koolhaas to offer a variety of cross cultural exhibitions and live events (Yeo 2009). The specific location, in the grounds of the Gyeonghui Palace, was chosen to create a juxtaposition of modernity in a historic environment, while the wider location of Korea was seen as a commitment to the Asian market (Prada 2009). Chosen as the brand's key communication platform in 2009, this innovative project received considerable publicity across a variety of sectors (Yeo 2009). This year in Berlin, Calvin Klein launched its largest ever European fashion event through a collaboration with Germany's leading experimental architect, J Meyer H. In an attempt to create a deliberate alternative to the conventional fashion show, the exhibit was located in a disused industrial building (Lovell 2010). A 'curated' approach was adopted, with fashion garments displayed on a living installation of 50 models surrounded by large abstract sculptural forms (Alexander 2010).

These three projects are characterised by high cultural and media impact, high risk, and a temporary nature. Clearly, the purpose is to convey meaning (however abstract) about the fashion brand to an existing and/or new audience. The creative collaboration between the fashion designer and the architect is the essence of the partnership, creating a point of differentiation and informing the brand's visual identity while overt connections to the brand's conventional marketing initiatives remain minimised. The temporary aspect is also significant, implying an inherent 'must-see' appeal due to the novelty of the installation and its 'limited availability'.

Having identified the three categories of collaborations between fashion designers and architects, the following sections address the motives for engaging in such an exchange.

FUNCTION

The organisation of space is equally centric to the industries of fashion and architecture; in essence, both are rooted in the task of enclosing space around the human body (Quinn 2003). Though architecture and fashion share mutual tendencies towards design, the immediacy of fashion versus the inherent permanence of architecture presents very real tensions in collaboration. Nevertheless, new partnerships continue to evolve, exploring issues of body, shelter and identity from both architectural and fashion design perspectives (Miles 2009).

Regarded as the 'tipping point' for architect-fashion designer collaborations, the 1990's witnessed global retail conglomerates investing heavily in fashion brands. This forged new dialogue between retail architects and fashion designers as part of branding strategies that aimed to create globally resonant brands with consistent positioning and differentiated appeal (Quinn 2003). It is during this period where the foundation for key motives between architectural and fashion design collaborations began to emerge. These intentions may be categorised in relation to brand positioning (Wasik 1996; Hansich 2006; Moore, Doherty and Doyle 2006), marketing communications programs (Quinn 2003) and general growth strategies.

Brand Positioning

Branding is defined by Aaker (2000) as a function of both identity and positioning, whereby the former influences and directs the latter. Considering that the majority of fashion brands partaking in collaborative efforts already possess established and distinct identities, the key branding dimensions relevant to architectural collaborations is in emphasising or manipulating specific dimensions to solidify or obtain a novel brand position (Kapferer 2004; Aaker 1996). The previously outlined collaboration between Hadid and fashion powerhouse Chanel clearly demonstrates these tendencies (Seno 2008). This travelling art exhibition functioned to engage consumers, media and industry in an entirely new interactive experience which was traditionally unconventional for the Chanel brand (Itzkoff 2008). Visitors to the exhibition were immersed into the brand's world, describing the experience as "being part of what feels like a very elaborate Chanel commercial" (Seno 2008). To further associate the Chanel identity with the worlds of art and architecture, the 'container' showcased twenty original artistic works inspired by an iconic Chanel product (Seno 2008). This enabled global consumers to experience the brand heritage, solidifying Chanel's associations with art and architecture, and contributing to a more sophisticated, and dynamic brand identity and position.

Kapferer (2004) suggests consumers identify brands primarily from a product perspective; however the creation of experiences allows for a more holistic brand identity to be expressed. Leading fashion store architect, Michael Gabellini suggests that store design is a most prominent means of brand communication and interaction: "the store design doesn't so much 'symbolize' a brand as embody it" (Wigley and Larsen 2010). When carefully crafted stores are the product of a synergetic relationship between fashion and architecture, the results can be inspiring examples of brand positioning for both the architect and the fashion designer (Moore and Docherty 2007). As Quinn (2003: 16) reiterates, "Just as dress can be adopted and adapted as a means of personal expression, architecture has been used to express collective identity, values and status". Through consistently emphasising or introducing new values, collaboration, can provide a strong mechanism for positioning and brand identity development lending credibility and authenticity (Wasik 1996).

As previously indicated, Prada's patronage to architecture has been regarded as significant to its influence on fashion design (Quinn 2003). The 'Prada Transformer' was described by its architect, Koolhaas, as being 'a single tool to serve the purposes of two or three sides of Prada" (Vezzoli 2008). Koolhaas confirms the positioning capabilities served by the project - through its ability to associate different dimensions of both Prada and Koolhaas' respective identities - but also posits the structure itself as a communications tool. Herein lies the second function of architectural and fashion design collaborations - as a marketing and communications tool. Collaborations on projects such as the 'Prada Transformer' overtly explore the potential of using permanent or temporary architectural spaces as a communications medium, from which a fashion brand may transcend the confines of a garment into an interactive spatial system (Quinn 2003); "the Prada Transformer is a machine for making publicity" (Heathcote 2009:26). David McNulty, Head of Architecture at Louis Vuitton (LV) confirms by explaining how they "utilize architecture as an advertising instrument for the label" (Hansich 2006). The benefits of marketing hype aside, fashion and architecture collaborations also act as articulation devices to consolidate a brand's identity across international markets (Quinn 2003).

The opportunity to complement or extend a brand identity is often manifested in appeals to new target markets or the development of new products. As well as providing new revenue streams, extensions have the capacity to strengthen the core values of established brands (Aaker 2000; Urde 2001). A successful extension is typically derived from considering product portfolio gaps in the context of anticipated market developments (Elliott and Percy 2007), implying that branding strategy may be altered by developments independent of the brand itself. Thus, fashion companies' collaborations with architects may be motivated by a desire to benefit from of an apparently sympathetic engagement with a recognised wider popular interest in architecture and design. Whether overt or covert communication presides, the collaborations may reveal insight to specific benefits sought. For example, Gucci's sponsorship of Richard Serra's architectural exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2001 was subtle, aiming to associate its brand with the architect's creative credibility rather than place their own brand in the limelight (Quinn 2003). Such an association lends opportunities to connect with potential new consumer groups whose values and interests are pertinent to the collaborators' work. Conversely, Hadid's shoe design collaboration with Lacoste was more overt in intention, garnering publicity for both the brand and the architect. As well as accruing coverage for Lacoste (a brand less commonly noted for creativity), this partnership proved successful for Hadid, leading to a second fashion design commission with Brazilian footwear label Melissa (Almeida 2009). Hadid's success in partnering with fashion brands has brought her own brand into mainstream consciousness and further cemented her 'starchitect' status. Similarly, Giorgio Armani manipulates brand positioning through his architectural collaborations with Studio Fuksas, adapting the design aesthetic of his stores to target different segments of consumers (Fuksas 2010). Here, Armani leverages the partnership to support the brand's multi-dimensional growth strategy of continual market and product diversification (Hansich 2006; Moore and Wigley 2004).

Figure 7: Armani '5th Avenue', Concept Store, New York City. Architects: Doriana and Massimiliano Fuksas (Interior view)

Figure 8: Armani '5th Avenue', Concept Store, New York City. Architects: Doriana and Massimiliano Fuksas (Detail view)

Whichever the function of or motive for collaboration between fashion designers and architects, both must be equally cognisant of consumer and brand issues, needs and desires (Urde 2001; Quinn 2003; Wigley 2010). This dual focus further emphasises the innate and intimate relationship between fashion and architecture in their fundamental roles of influencing and organising space.

Summary

To summarise, this paper has highlighted a growing global trend for fashion designer and architect collaborations within the last decade specifically. Three major sources of partnership were identified: stores, products and 'third space' cultural projects. Stores were the most traditional area for joint development and this phenomenon is characterised through the extravagant co-designing of the permanent flagship stores of luxury fashion brands. Product collaborations have been a more recent movement and have taken the form of a temporary range of co-branded items with the design signature of the architect complimenting the fashion brand's core product design, this has been evident at all levels of the market. The form of third space collaborations are again temporary in nature and are most often focused on art and on magnifying the cultural and experiential connection between fashion and architecture. Again it is predominately the luxury fashion brands who have engaged in this type of project.

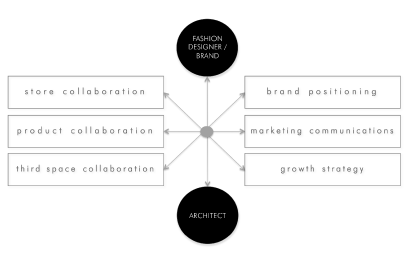

With respect to the function of fashion designer and architect collaborations, the nature of the collaborative program may be both influenced by or influence the function which it serves. Three such motives for pursuing architect-fashion designer relations are identified as to serve brand positioning, marketing communications and growth strategies. These partnerships extend beyond traditional tactics to enhance branding strategy and create a layering of meanings that may strongly resonate with consumers, industry and media. Whether through product, store design or third space, architecture and fashion design collaborative projects can be read as opportunities for covert or overt associations and meanings. Figure 9, below, proposes a typology of the relationship between architect and fashion designer in relation to the form and function of interaction and benefits sought.

Figure 9: A Typology of Fashion Designer and Architect Collaborations (Stacy Anderson)

The paper also highlights opportunity for additional research and investigation on the factors that influence collaborative suitability and collaborative success. Though the design palette may differ, the mentalities shared between architect and fashion designer towards organizing space around the human form perpetually unite these disciplines in an intimate discourse of mutual exchange; as asserted by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright asserts, "form and function are one" (Lentz 2009).

References

Aaker, D. (1996). Building Strong Brands. Free Press: New York.

Aaker, D. (2000) Brand Leadership. Free Press: New York.

Alexander, A. (2010) Klein's Berlin Brigade. Retrieved 17 June 2010, from Vogue: http://www.vogue.co.uk/news/daily/100617-calvin-klein-plans-berlin-event.aspx

Almeida, I. (2009) Big-name Architects start Designing Fashion. Retrieved 6 April 2009, from Wall Street Journal: http://online.wsj.com/article/NA_WSJ_PUB:SB123630652361848267.html

Barnett, L. (2008) A Chanel Shutdown. Retrieved 22 December 2008, from Vogue: http://www.vogue.co.uk/news/daily/081222-chanel-pulls-mobile-art-project.aspx

Barreneche, R. A. (2005) New Retail. London: Phaidon Press.

Battissta, A. (2010) Architectural Fashionscapes. Retrieved 21 August 2010, from Dazed Digital:

http://www.dazeddigital.com/ArtsAndCulture/article/8018/1/Architectural_Fashionscapes

Bingham, N. (2005) The New Boutique. London: Merrell.

Carr, A. (2007) Retail Design Ideas: storytelling. Retrieved 8 February 2008, from WGSN: http://www.wgsn-edu.com/members/retail-talk/features/rt2007mar08_019634?from=search

Chasser, A., H. & Wolfe, J., C. (2010) Brand Rewired: Connecting Branding, Creativity and Intellectual Property. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Chow, P. (2003) "Under the Net". The Architectural Review. October, p46-51.

Curtis, E. & Watson, H. (2010) Fashion Retail. London: John Wiley & Sons.

de Chernatony, L. McDonald, M. (2003) Creating Powerful Brands (3rd edition). Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

Elliott, R., & Percy, L. (2007) Strategic Brand Management. Oxford University Press.

Fuksas (2009) Giorgio Armani Opens Armani 5th Avenue in New York. http://www.fuksas.it/data/news/051/download.pdf.

Golbin, P. (2009) Madeline Vionnet. London: Rizzoli

Hansich, R. (2006) Absolutely Fabulous!: Architecture for Fashion. Munich: Prestel Publishing.

Heathcote, E. (2009) "A machine for making publicity; Architects: Office for Metropolitan Architecture". Icon, 07/09, p.54-60.

Huxam, C. (1996) Creating Collaborative Advantage. London: Sage.

Itzkoff, D. (2008) Chanel Pavilion Tour is Cancelled. Retrieved 28 July 2010, from The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/23/arts/design/23arts-CHANELPAVILI_BRF.html

Jana, R. (2007) Peter Marino's Brand Buildings. Retrieved 10 May 2007, from Business Week: http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/may2007/id20070510_881776.htm>

Kapferer, J. (2004) The New Strategic Brand Management (3rd edition). London: Logan Page.

Laub, A. (2010) "Milan Design Week: Top Installations". Retrieved 4 May 2010 from WGSN: http://www.wgsn.com.

Lentz, L. (2009) "Record Interiors". Architectural Record, 07/09.

Lovell, S. (2010) Calvin Klein collaborates with J Mayer H. Retrieved 22 July 2010, from Wallpaper: http://www.wallpaper.com/fashion/calvin-klein-collaborates-with-juumlrgen-mayer-h/4721

Menkes, S. (2009) London Exhibit Probes Parallels Between Architecture and Fashion. Retrieved 28 April 2008, from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/28/style/28iht-fbones.1.12392875.html

Mikunda, C. (2004) Brand Lands, Hot Spots & Cool Spaces. London: Kogan Page.

Miles, G. (2009) Skin & Bones: Parallel Practices between Fashion and Architecture (Exhibition Guide). Retrieved 1 November 2010, from: http://www.somersethouse.org.uk/documents/skinbones_exhibition_guide.pdf

Moore, C. M. and Doherty, A.M. (2007) "The International Flagship Stores of Luxury Fashion Retailers" in Hines, T. & Bruce, M., Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues (2nd Edition), Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Moore, C. M. & Wigley, S., M. (2004) The Anatomy of an International Fashion Retailer - The Giorgio Armani Group. British Academy of Management Conference, St. Andrews, August 27th-29th.

Mores, C. M. (2006) From Fiorucci to the Guerrilla Stores: Shop Displays in Architecture, Marketing and Communications. Oxford: Winsor Books.

Mosse, A. (2010) Architectural Knitted Surfaces Workshop. Retrieved 5 August 2010, from WGSN: http://www.wgsn-edu.com.

Oxford English Dictionary (2010) Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford: Open University Press.

Prada, M. (2009) The Prada Transformer. Retrieved 1 November 2010, http://www.prada-transformer.com/assets/pdf/project.pdf.

Prada, M. & Bertelli, P. (2010) Prada. Milan: Fondazione Prada.

Quinn, B. (2003) The Fashion of Architecture. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Reynolds, J. Howard, E., Cuthbertson & C., Hristov, L. (2007) "Perspectives on retail format innovation: relating theory and practice". International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. Volume: 35 Issue: 8. pp 647-660.

Riewolt, O. (2002) Brandscaping: Worlds of Experience in Retail Design. Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag.

Seno, A. (2008) It's All in The (Chanel) Bag: Art meets Fashion. Retrieved 24 April 2008, from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/24/style/24iht-chanelart.1.11361688.html

Tungate, M. (2009) Fashion Brands: From Armani to Zara. London: Kogan Page.

Uggla, H. (2004) "The Brand Association Base: A Conceptual Model for Strategically Leveraging Partner Brand Equity". The Journal of Brand Management. Vol. 12, No. 2, pp 105-123.

Urde, M. (2001) "Core value-based corporate brand building". European Journal of Marketing. 37 (7/8), pp.1017-1040.

Vezzoli, F. (2008) "Prada Transformer". Interview Magazine. Retrieved 28 July 2010, http://www.interviewmagazine.com/culture/prada-transformer/2/

Wasik, J. (1996) Green Marketing and Management: A Global Perspective. Cambridge: Blackwell.

WGSN, (2010) Louis Vuitton prepares to open its "most luxurious" ever store in London. Retrieved 19 May 2010, from WGSN: http://www.wgsn-edu.com.

Wigley, S. M & Larsen, E. (2010) "The Architecture of Fashion Retailing: Michael Gabellini and the Creation of Brand Environments". European Institute of Retailing and Services Studies Conference, Istanbul July 2nd-5th.

Wu, B. (2008) Chanel Mobile Art. Retrieved 28 February 2008, from WGSN: http://www.wgsn-edu.com.

Yeo, H, I. (2009) 'Prada Transformer, Seoul'. Retrieved 24 April 2009, from WGSN: http://www.wgsn-edu.com.