Introduction

Comic book narratives are multimodal literature because its stories are told using an almost seamless blend of text and image. Each visual narrative is generated from a creative process involving an author and an artist (who may be one and the same person), but most modern comics are produced using creative teams, which adds letterers, colorists, and inkers into the process. Therefore, comic book production is a collaborative effort, but such cooperation is not limited to this process of creation. Comics are intended for consumption on a consistent basis and audiences gain access into this unique genre of literature through an act of reading. However, reading comics differs from traditional texts because of its visual nature, as Will Eisner explains in Comics and Sequential Art:

The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills. The regimens of art (eg. perspective, symmetry, brush stroke) and the regimens of literature (eg. grammar, plot, syntax) become superimposed upon each other. The reading of the comic book is an act of both aesthetic perception and intellectual pursuit (Eisner 1990: 8).

Because comics combine precepts from literature and art, understanding comics as interactive media negotiated with its audience through reading requires a combined approach using rhetoric and poetics with reader-response theory. Approaching comics from this framework will help us explore how the genre lends itself toward rhetorical analysis in its stories along with considerations about how comics? dependency on visual narrative techniques establishes a unified community based on that necessary act of reading. Our starting point will be considering comics from Scott McCloud?s perspective, whose books are often cited in comic scholarship, but not without scrutinizing some of his concepts such as comics? origin.

Origin of Comics According to Scott McCloud

Scott McCloud is a recognized name among comic book readers because of his reputation as a career comic writer and artist who worked on several mainstream titles for comic book publishers like DC and Marvel Comics, but McCloud is also known within scholarly communities because of his books about comics. McCloud uses a comic book format to discuss comics in his books, which is a unique presentation, allowing him to explain topics such as how an audience reads comics and which techniques are available for artists to produce comics demonstrated in its own language. Because of the visual format and selection of topics, McCloud continues and expands upon the work of the late Will Eisner, whose Comics and Sequential Art predates McCloud by almost a decade. Eisner and McCloud provide comics with a potential theoretical framework that point toward future directions of scholarship being pursued by other comic scholars, but if one of those directions is going to be rhetorical analysis, then we must call into question McCloud?s methodology and interrogate it before such an analysis becomes possible. We will begin with looking at McCloud?s questionable origin of comics in Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art.

McCloud acknowledges a commonly agreed upon time period among comic scholars for starting a history of comics as being the nineteenth-century, but instead of providing a rationale for why that particular time, McCloud proposes an argument for tracing comics? origin farther back in time. For McCloud, comics may be traced back as early as ancient Egypt when hieroglyphs appeared on pyramid walls and on sarcophaguses, demonstrating a visual means of communication for an initiated audience. However, before looking at the details of McCloud?s argument, we already have a problem. The combination of sequential text and image as communication is what McCloud depends upon as a theme entitling him to claim comics? origin prior to the nineteenth-century. In McCloud?s version of comics history, other ancient examples of comics include a painted screenfold thirty-six feet in length called "Tiger?s-Claw" depicting a hero named 8-Deer and his quest to kill a rival prince, but it also includes the Bayeux Tapestry from 1066 depicting the Norman Conquest. The problem here is not which ancient texts McCloud chose as examples of comics from antiquity, but instead his dependency upon text and image in sequence is a retroactive application of a modern perspective. Although we may question McCloud?s earlier history of comics based on his approach, the attempt itself implies a connection between what Walter Ong calls primary and secondary orality in Orality and Literacy with respect to comics, which we will examine after returning to McCloud?s use of hieroglyphs and its relation with language.

McCloud explains that those hieroglyphs represent individual words when translated into speech, which establishes a shared understanding about how information is transferred from one medium into another, as Havelock explains in The Muse Learns to Write:

The art (or science?) of writing in the Near East had through millennia slowly promoted the invention of signs that had phonetic values, as distinct from the visual ones symbolized in early Egyptian hieroglyphs. Progress in this direction had got as far as identifying the syllables of a spoken tongue and assigning "characters" to them (Havelock 1986: 59).

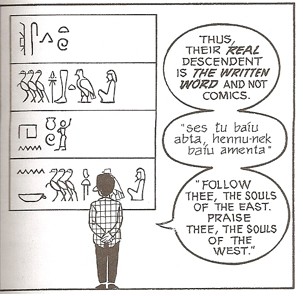

However, a problem occurs here because McCloud shows us this sequence of Egyptian hieroglyphs and not only reads it aloud in Egyptian, but also translates it into modern English:

The problem is not concerning McCloud?s textual pronunciation of ancient Egyptian, nor is it his apparent ability to translate into modern English, but rather in his capability to read the sequence as words. Havelock reminds us that assigning characters to sounds becomes problematic because "The number of syllables is tremendous, and the resultant sign system became difficult to memorize and cumbrous to use" and ancient Egyptian culture is no exception (Havelock 1986: 59). Havelock demonstrates this problem using the Phoenician language and its consonantal set "ka ke ki ko ku." Each pairing of letters in the set is an individual sound indicated using a single symbol k, but that symbol is not used for the letter itself. According to Havelock, a reader working with this consonantal set must decide which sound is associated with the symbol k each time it appears, so while McCloud?s reading of ancient Egyptian appears impressive its accuracy remains questionable. Although McCloud?s origin of comics suffers significantly from reverse projection of modern culture upon history, McCloud?s tracing of text-image combinations in sequence identify a significant event during the nineteenth-century as the invention of printing, which we mentioned earlier as a starting point most comic scholars agree upon for determining when comics originated. Thus far, we explored a questionable history of comics proposed by Scott McCloud, but comics are indebted to print practices and visual aesthetics used in art, which makes defining comics quite difficult as McCloud shows us.

Defining Comics, Alphabets, and Oralities

McCloud makes an attempt to define "comics" in his opening chapter from his first book, Understanding Comics, which proves itself as a difficult task demonstrated by a humorous interaction between McCloud and a fictional audience. McCloud uses Eisner?s description of comics as "Sequential Art" as a starting point and together McCloud and his audience pursue changing that description into a definition that may be found in a dictionary. The first suggestion calls for identifying a more specific type of art, so "Sequential Art" becomes "Sequential Visual Art," which raises a question from the audience about animation. McCloud begins considering animation and its possibilities with respect to film, but he leaves it behind and does not return to it with any further detail until his third book, Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels (McCloud 2006: 7). However, thinking about animation changes "Sequential Visual Art" into "Juxtaposed Sequential Visual Art" and another audience member challenges the use of "art," stating a value judgment may be derived from it. As a correction, McCloud offers "Juxtaposed Sequential Static Images," which sounds arbitrary to the audience, so he comes up with "Juxtaposed Static Images in Deliberate Sequence." However, that definition also comes under fire from an audience member named Bob who points out that description may be applied to words because "Letters are static images, right? When they?re arranged in a deliberate sequence, placed next to each other, we call them words!" (McCloud 1993: 8). Audience member Bob is raising an important point we must consider as rhetoricians and an important hurdle for comics to overcome before we attempt analyzing them using rhetorical theory, but McCloud only addresses Bob?s concern by changing his definition to read: "Juxtaposed Pictorial and Other Images in Deliberate Sequence" and then presents his last attempt at defining comics as: "Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer" (McCloud 1993: 9).

Bob?s response to McCloud?s definition of comics as "Juxtaposed Static Images in Deliberate Sequence" is one worth further consideration from a rhetorical perspective because the implications for words extend beyond sequential letters used to communicate upon visual recognition. However, Bob?s mentioning of words is a good place for us to start considering how we consume language and make use of it as a tool. Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore revise our understanding of words and its uses in communication, whether spoken or written, from a seemingly passive activity into a process capable of accomplishing interactivity as described in The Medium is the Massage: "The alphabet, for instance, is a technology that is absorbed by the very young child in a completely unconscious manner, by osmosis so to speak" so that "Words and the meaning of words predispose the child to think and act automatically in certain ways" therefore "The alphabet and print technology fostered and encouraged a fragmenting process, a process of specialism and of detachment" (McLuhan and Fiore 1967: 8).

For McLuhan and Fiore, then, speaking and writing are mechanical processes that depend upon individuals consuming letters and words to create meaning within a person?s mind. If communication is a goal for using language, then speaking and writing account for transmission, but intended receivers require a method for performing those tasks as a means of completing the communicative action. Here we may turn again to the concept of an alphabet as McLuhan and Fiore suggest saying:

The alphabet is a construct of fragmented bits and parts which have no semantic meaning in themselves, and which must be strung together in a line, bead-like and in a prescribed order (McLuhan and Fiore 1967: 44).

Reading and acts of reading on an individual?s part then become a specific fragmented procedure we condition ourselves to perform over time. As a result of this process, McLuhan and Fiore suggest that we develop a sense of individualism based upon detachment, or non-involvement happening because of our sustained silent efforts to interpret and consume words formed from letters. Reading may seem like something exclusive from writing and speaking, but actually, both are tightly intertwined and in order to understand how that is possible we must rephrase Bob?s initial question before investigating further. The question must change from one that addresses single letters and their relationship to language as an alphabet into one that asks about comics? place in the oral-literate tradition instead.

Walter Ong acknowledges and explores cultural differences between oral and literate societies in his book, Orality and Literacy, separating them into two distinct categories of orality. Ong describes primary orality as "a culture totally untouched by any knowledge of writing or print" and secondary orality refers to "present-day high-technology culture, in which a new orality is sustained by telephone, radio, television, and other electronic devices that depend for their existence and functioning on writing and print" (Ong 1982: 11). Ong realizes that primarily oral cultures? presence within modern society is much less pronounced than during previous eras and based upon Ong?s classifications, comics are an example of secondary orality because its existence as a medium is indebted to the printing press along with collaborative production efforts from writers and artists, but comics also possess some primary oral culture characteristics. Therefore, before turning our attention toward secondary orality and comics, we must spend more time on Ong?s concept of primary orality.

During ancient Greco-Roman period, primary orality flourished since public forums were common and a preferred presentation style involved reciting speeches from memory. A speaker?s ability to memorize lengthy speeches and repeat them verbatim is not exclusive to the realm of public speaking, though, because writing developed alongside speaking during this period. However, writing served an educational purpose as public speakers learned through sequential written exercises called the progymnasmata, which is an important relationship between spoken and written word Ong overlooks when he distinguishes primary and secondary orality. For Ong, primary and secondary orality definitions are dependent upon an inverse relationship between oral and written communication. Therefore, primary orality is recognized as the presence of spoken language while writing is assumed diminished or absent, but secondary orality is characterized as the presence of written language while speech is diminished or absent. Ong believes technology is responsible for shifting cultures from primary to secondary orality and presents readers with a list containing progressively improving writing tools and surfaces predating our contemporary print technology saying:

Instead of evenly surfaced machine-made paper and relatively durable ball-point pens, the early writer had more recalcitrant technological equipment. For writing surfaces, he had wet clay bricks, animal skins (parchment, vellum) scraped free of fat and hair, often smoothed with pumice and whitened with chalk, frequently reprocessed by scraping off an earlier text (palimpsets) (Ong 1982: 93).

Although a departure from oral communication may be traced from Ong?s presented list, we must be cautious about naming its replacement written communication. The changing writing surfaces hints at sight playing a role, allowing for increased attention toward visual characteristics, which is a unique element for comics. However, before we examine visual elements comics possess from a rhetorical perspective, we must provide a stronger transition between primary and secondary orality.

If a primarily oral culture is one devoid of technology and composition, then its members are completely dependent upon spoken word as a form of communication, which is one reason Ong identifies for its rarity in modern society. Eric A. Havelock describes the continued phenomenon of interacting using words in The Muse Learns to Write saying:

We can extend our view to include a verbal exchange between one individual and a group, an audience, and then go on still further to think of it as something spoken silently, by a writer who writes down what he is saying so that another person can read what he says instead of just hearing it (Havelock 1986: 63).

Havelock identifies a cultural transition from primary to secondary orality suggesting that technology is not responsible for diminishing primary orality?s societal role. Technology becomes similar to a buffer between two or more agents attempting communication because of its ability to change words from being interpreted and comprehended externally using hearing, into something which may be consumed visually through what Ong calls interiorization. According to Havelock, orality becoming virtually obsolete is because "The use of vision directed to the recall of what had been spoken (Homer) was replaced by its use to invent a textual discourse (Thucydides, Plato)" signaling a change from spoken to written language as a dominant communication method. The shift in discourse diminished primary orality within mainstream cultures and allowed secondary orality to be born as well as embraced. The hold secondary orality maintains over culture will last until our present time and beyond, but along with it comes new narrative possibilities such as comics.

As a result from increased use of vision and association of memory with what a person sees, a new type of echo is created, one that is projected through what Ong calls interiorization. Havelock prefers to call that same action "thematic echo" and he provides an example from Homer?s Iliad saying "to give one of the more obvious examples, all the conferences between Achilles and his mother recurring throughout the extent of twenty-four books have a family resemblance. Yet within the resemblances, something new also occurs" (Havelock 1986: 73).

Ong and Havelock provide strong arguments about distinguishing primary and secondary orality, but only when two different elements are conflicted such as speech and written communication. However, comics involve visual elements along with text and speech properties, therefore, we must frame comics within an understanding that accounts for three or more conflicted elements before proceeding further. Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin give us an alternative understanding described in Remediation: Understanding New Media saying:

We call the representation of one medium in another remediation, and we will argue that remediation is a defining characteristic of the new digital media. What might seem at first to be an esoteric practice is so widespread that we can identify a spectrum of different ways in which digital media remediate their predecessors, a spectrum depending on the degree of perceived competition or rivalry between the new media and the old (Bolter and Grusin 2000: 45).

Approaching a transitional difference between primary and secondary orality as a rivalry between different media is more appropriate than dismissing one medium or another, but because secondary orality is related with print technology and everything derived from it, a rivalry is happening between three different elements when we consider comics through a rhetorical lens: oral, written, and visual communication.

Now that we examined both primary and secondary oralities with respect to communication as a means of constructing a history of comics appropriate for rhetorical application, we are now prepared to consider comic books? use of secondary orality, but more importantly to address potential objections prior to looking at a specific comic book narrative. However, before we continue such a journey, we must first qualify comics as a genre toward this end using a more interior look at the medium. Therefore, let us turn our attention to Aristotle and his Poetics as a starting point.

Comic Books, Aristotle?s Poetics, and Aristotelian Unity

Aristotle is primarily concerned with tragic drama and its conventions in his Poetics as he provides a manual about how such plays are constructed. For ancient Greeks, drama functioned as a visual entertainment medium, similar to modern films or comic books. Understanding comic book production alongside film is easier for comprehension if we envision each part as a layer resulting in a completed comic book beginning with a writer. Aristotle considered dramatists as mimetic artists because plays presented representations of reality in its situations, locations, and characters. He says that mimetic artists "portray people in action," and "since these people must be either good or bad [?] they can portray people better than ourselves, worse than ourselves, or on the same level (Halliwell 1987: 32). Comic book writers are also mimetic artists then because monthly titles feature a cast of characters dealing with a given situation and are either good or bad. These characters are also heroes, villains, or non-metahumans4 in accordance with Aristotle?s types of portrayal above, respectively. Comic settings also contribute to mimesis because these are sometimes locations from our reality, such as New York City, which is home for heroes such as Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four in the Marvel Universe. Alternatively, DC Comics sets most of its offerings in fictional cities like Metropolis or Gotham City, but even these invented locales must be based upon real-world equivalents.

Eisner explains how a comic book writer assumes the roles of scripter and director because each page readers consume is usually written out as a stage script, with directions and dialogue resembling a printed play, based on how a writer envisions his or her story. As a script, then, a comic book becomes a form of dramatic enactment and overcomes Aristotle?s disdain toward narrative. However, we must give Aristotle the benefit of doubt since it was impossible for him to foresee how successful the novel would become in our modern time. Once a writer finishes a script, then an artist takes it and becomes like a cameraperson, responsible for providing images that change a description from something abstract into something concrete. An artist also becomes an actor as he or she draws scenes using agents set forth in a script by the writer, but decisions such as expressive gestures and postures are left up to the artist sometimes with minimal description from the writer.

Eisner practiced comic book production as both writer and artist, which resulted in more work for an individual, but doing so avoids potential collaborative problems as he describes saying:

The departure from the work of a single individual to that of a team is generally due to the exigency of time. More often the publisher ordains it out of a need to meet publication schedules, control his property when he owns a character, or when his editor assembles a team to suit an editorial thrust (Eisner 1990: 123).

As a result, Eisner identifies a potential failure of communication between writer and artist because sometimes a writer may provide a minimal amount of information about plot, for instance. Eisner says that "The artist proceeds to create an entire sequence of art, composing his panels around a general assumption of unwritten dialogue and the satisfaction of his perception of the plot?s requirements" and an artist?s product is then sent back to the writer for him or her to supply dialogue. Scott McCloud elaborates upon Eisner?s pitfall in Understanding Comics using a fictional example involving "Artie" (an artist) and "Rita" (a writer). Artie and Rita begin with a common idea to represent: a face. Artie imagines a face as a smiley and Rita associates a face with the word itself. Both people work individually on perfecting his or her craft in artistic technique and creative writing, respectively, but Artie and Rita are distanced too far from their common idea to be compatible as a result of research and practice (McCloud 1993: 48). Despite creative differences that may arise between a writer and an artist when collaborating, synthesizing an artist?s images with a writer?s script changes the comic book from being a dramatic enactment into a visual spectacle, which is sought after in tragic drama because audiences are attracted to such representations. Final touches require moving a comic from an artist to a letterer who will add dialogue to the blank word balloons drawn by the artist.

All comic book writers, artists, and letterers are performing what Aristotle would call techne, which Halliwell defines in Aristotle?s Poetics as "a practical skill" and "systematic knowledge or experience which underlies it" resulting in a rhetorical effect toward a given audience, such as comic book readers (Halliwell 1987: 44). Eisner, like Aristotle, strongly believed a connection exists between skill and experience as shown when Eisner discusses how frames function within comics. Frames, or panels, are individual units of narrative featured in comics containing an image and text sequentially. As our above discussion about writer-artist collaboration points out, typically a writer controls overall plot and dialogue, while an artist determines how those ideas are represented as a visual sequence. However, we must not mistake comic panels for cinematic frames despite similarities, as Eisner reminds us when he acknowledges a limitation of film being its dependence upon technology for consumption. Eisner elaborates on film?s limitation separating it from comics saying:

The viewer of a film is prevented from seeing the next frame before the creator permits it because these frames, printed on strips of transparent film, are shown one at a time (Eisner 1990: 40).

Another source of contention and distancing of comics from film occurs for Eisner if we consider the roles of an audience while watching a movie and reading a comic. Audiences watching a performance or movie are participating in a passive action since little or no interaction occurs between an audience and a stage (Eisner 1990: 40). A reading experience with comics differs from a theater experience because reading visually is an interactive process, which we will explore further later on, but for now it is important that we understand comics as being capable of showing all frames simultaneously as a layout on a page while guiding a reader?s experience with panels and visual cues.

Comic books as a genre must still overcome one important objection about their plot-structure before we depart from Aristotle?s Poetics. Aristotle says "Of simple plot-structures and actions the worst are episodic. I call an ?episodic? plot-structure one in which the episodes follow in a succession which is neither probable nor necessary" (Halliwell 1987: 41). Aristotle elaborates with an explanation about how such episodes are unified and thus problematic since

Unity, we have seen, entails a kind of cohesive ?logic? in the sequence of action dramatized by tragedy; each link in the dramatic chain must be firmly interlocked with what precedes and follows it, and the limits of this structure must be bounded in a way which does not require us to move outside them in order to understand the internal significance of the action (Halliwell 1987: 105).

Comic book series are structured as episodes because its stories are told from one monthly installment to another, Halliwell provides a loophole in Aristotle?s logic. Halliwell claims that "when we see or read a unified tragedy, it is the inner coherence, and hence the intelligibility, of the action which we recognize and respond to" (Halliwell 1987: 103). Comic books are able to achieve this "inner coherence" if we look beyond them as a sequence of individual issues numbered accordingly. These issues sometimes tell one story across many months and those instances are called "story arcs." If story arcs are collected as a whole, then those form one coherent series and removing any individual issue unravels inner cohesion from that story arc along with the whole series.

Comics also achieve unity in an Aristotelian sense through Halliwell?s "inner cohesion" on a local level when we consider how panels are traditionally arranged on a given page. Previously we mentioned how each panel shown functions as individual and sequential narrative units constructed collaboratively between a writer and an artist. Looking more closely at this creative process and focusing upon an artist?s perspective when he or she works with an author?s script will help demonstrate how comic panels fulfill requirements for Aristotelian unity. Scott McCloud identifies and explains five choicesa artists face whenever drawing a comic in Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels, but for our purposes, we will narrow them down to one: Choice of Moment. McCloud defines Choice of Moment as when an artist is "deciding which moments to include in a comics story and which to leave out" which again sounds much like film with respect to pre-production storyboarding. McCloud illustrates his point with the following eight-panel sequence depicting five events:

Here we are shown a simple narrative told using comic panels depicting a man walking along and he finds a key. After picking up the key, the man comes upon a door, which prompts him to unlock it using the key. As a result, a lion attacks him. McCloud is using this example of "A Man Walking" as an exercise in understanding clarity within comic art, but it also demonstrates a convention of reading comics involving traditional panel order. For Western audiences, readers probably deciphered these eight panels beginning from the upper-left moving to the right until the fourth panel and then repeating that procedure on the second row until the final panel, like a typewriter. If we remove any panel from the above sequence, then our narrative?s meaning changes because its unity is disrupted. For instance, McCloud removes the second panel and "A key found?becomes a key retrieved" and when he removes the fourth panel and continues saying "or a key found?becomes the finding of an unidentified object" (McCloud 2006: 13). McCloud says that our narrative above is easily understood and memorable because it is told using only eight panels in a specific order, whereas many more panels may be added, which raises our final point about comics and Aristotelian unity with respect toward how readers interpret sequential panels.

Eisner explains the relationship between panels using a combined understanding about posture and photography. For Eisner, each panel is like a snapshot, capturing an individual moment "selected out of a sequence of related moments in a single action [?] one posture must be selected out of a flow of movements in order to tell a segment of a story. It is then frozen into the panel in a block of time" (Eisner 1990: 105). McCloud agrees with Eisner, but he also adds in Understanding Comics that readers supplying missing actions before and after a panel do so through acts of "closure." (McCloud 1993: 63). Closure happens between the panels because an audience?s imagination supplies missing information prompted by the blank space and then interprets it as a single action. For example, in Understanding Comics, McCloud depicts a two-panel sequence showing a man raising an axe while chasing someone in one panel and then a city skyline with "EEYAA!!" written across it in the next panel. Using these two panels, McCloud points out "Every act committed to paper by the comics artist is aided and abetted by a silent accomplice. An equal partner in crime known as the reader" who determines specifics about the axe dropping, how hard that axe falls, where it lands, who screams, and why (McCloud 1993: 68). However, before considering readers, we must further examine comic book artists as potential visual rhetoricians.

Comic Book Artists as Visual Rhetoricians

As mentioned previously, comics represent a specific genre within multimodal composition, which distinguishes itself from other texts because of its visual nature, but something more interesting from a rhetorical perspective is how comics resolve tensions between written, spoken, and visual communication. A resolution among these three primary communication modes is best accomplished when we consider comic book artists as visual rhetoricians. As visual rhetoricians, comic book artists? decisions about how comic panels appear when a reader interprets them become persuasive acts, which involve working with text and image properties together. The best example showing written, spoken, and visual communication simultaneously under a comic artist?s direction is a word balloon.

A word balloon?s basic function within a comic panel is presenting additional information intended to assist readers with interpretation and often appears as speech surrounded with a border placed near a speaker within the panel. However, McCloud points out in Making Comics that "As balloons became more extensively employed their outlines were made to serve as more than simple enclosures for speech. Soon they were given the task of adding meaning and conveying the character of sound to the narrative," which became possible when artists show a word balloon?s border as something other than solid lines (McCloud 2006: 24). A comic book artist altering a word balloon?s border in order to achieve a desired effect is a persuasive act involving visual communication based on reading conventions shared between an artist and a reader. A comic artist?s choices about lettering within a word balloon brings together visual and written communication with spoken communication because dialogue is depicted as text on a page attributed to a speaker as indicated with a word balloon. However, comic artists also resolve tensions among these three communication methods through balancing how much information is presented with text or image alone.

In Making Comics, McCloud identifies seven possibilities for comic artists to show word and image within a narrative context. For our purposes, understanding word-specific combinations is most important for exploring visual possibilities (McCloud 2006: 130). According to McCloud, word-specific combinations allow comic artists numerous storytelling advantages, which is shown using Bob as his example. The text an artist might work with is "Bob was a happy baby. At 18, he went to war. At 36, he bought a house. He died at 72" and McCloud presents a four-panel sequence accompanying each possibility available to a comic artist saying:

You could illustrate the events in a fairly straightforward way?you could draw the whole thing using just hands?you could show a narrator speaking directly to the reader?you could even illustrate it entirely with symbols (McCloud 2006: 132).

Here we McCloud?s first four-panel sequence is most relevant because each panel demonstrates important properties from a visual rhetoric perspective. Although McCloud names many different methods for showing readers the same events, regardless of which method is chosen, certain visual elements remain the same and those elements reveal a grammar as Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen describe in Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. For Kress and van Leeuwen, an image may contain an Actor and a Goal and most interpretations are derived from this concept. An Actor is someone or something performing an action within the image and a Goal is someone or something being acted upon. An Actor-Goal relationship is dependent upon one direction or vector being portrayed within an image, which is best shown when McCloud depicts Bob and his wife looking at their new home in the third panel or when his wife and relatives are looking at his tombstone in the fourth panel, but if more than one Actor or Goal is shown, then each pair is interpreted as Interactors (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006: 63-66).

For example, McCloud shows readers Bob as a baby in his parents? arms in the first panel with parents looking down at him and Bob looking back at his parents. An Actor and Goal is definitely present because Bob?s parents are looking down at him, which makes them Actors and Bob the Goal, but Bob is also looking back at them, which makes him an Actor and his parents the Goal from his perspective. For Kress and van Leeuwen, multiple Actor-Goal vectors present within an image changes each Actor-Goal pair into Interactors. However, if an outside reader is interpreting an image, then an additional eyeline vector is introduced, thus Interactors become Phenomenon and the outside reader becomes a Reactor because the image as a whole is acting upon him or her (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006: 67). The number of participants and vectors present within any comic panel is a decision a comic artist makes, but his or her choices persuade us to interpret a given panel so that a specific message is received, therefore an artist is capable of being a visual rhetorician. However, a comic artist is not alone and often works with a writer or creative team, which means we must examine a writer?s role with narrative and how readers receive comics.

Narratives, Comic Books, and Readers

Turning our attention toward how we read comic books, or how we decipher written and visual language and interpret them as examples of communication, is a logical move requiring some qualification. For our purposes, we must return to Ong?s concepts of primary and secondary orality with respect toward his thoughts about reader-response theory, which we will need to examine the processes involved for consuming a hybrid literary genre such as comic books. Ong explains his position when he states:

It appears obvious that speech-act theory and reader-response theory could be extended and adapted to throw light on the use of radio and television (and the telephone as well). These technologies belong to the age of secondary orality (an orality not antecedent to writing and print, as primary orality is, but consequent upon and dependent upon writing and print). To be adapted to them, speech-act and reader-response theory need to be related first to primary orality (Ong 1982: 168).

Previously we explored both types of orality independently because Ong realizes that primary oral cultures are almost extinct aside from existing subcultures. Unfortunately, Ong desires classifying a majority of our modern society?s communication methods as secondary orality, but here he makes an exception for subjects addressed by reader-response theory so long as we may supply a bridge between the subject and primary orality. Building an appropriate bridge requires us to look again at Marshall McLuhan?s ideas on technology and globalization in Medium is the Massage.

For Ong, one lost element resulting from developed cultures transitioning from primary to secondary orality is a capacity for communicating using only acoustic means, or sound. Ong conveniently places modern technology into the secondary orality category, but it is important for us to realize that comics also qualify as secondary orality because of its existence as a remediation of print. McLuhan suggests that because of technology, societies are forming an alternative community, or "a world of total involvement in which everybody is so profoundly involved with everybody else and in which nobody can really imagine what private guilt can be anymore" thus "[?.] We live in a global village?a simultaneous happening. We are back in acoustic space. We have begun again to structure the primordial feeling, the tribal emotions from which a few centuries of literacy divorced us" (McLuhan and Fiore 1967: 61, 63).

However, something Ong overlooks is a modern audience?s ability to turn back outward once more, which we demonstrate whenever interacting with a device dependent upon our sight for interaction such as television. For instance, when we watch athletic events on television, we are supporting our favorite team and desire them to win against its opponent so we turn inward as we watch players perform actions that help their team win the game. Depending on the success or failure of those actions shown on television, we react and turn outward again, sometimes audibly toward the television as if those players may hear and respond to our words. Following an athletic event or other weekly program, viewers may seek out others who also witnessed the game on their own television and proceed to talk about what they saw on the screen. Discussing the game or program as a shared experience allows for sound and memory to help members communicate and doing so forms a temporary primary oral culture while simultaneously demonstrating a global village. The entire experience requires individuals to use sight, sound, and memory, which are also used whenever we read comics. Previously, we began our discussion about comic books by claiming the medium as a multimodal literary genre because of its combinations of text and image to tell those narratives. We already overcame Aristotle?s objections to episodic narrative and doing so shows us how reading comics is a collaborative act between rhetoric and poetics. However, we must consider future directions for scholarly pursuits about reading comics as a rhetorical act.

Conclusion

Our discussion about how rhetoric and poetics function within comics ends here, along with our current understanding about how comics are unique because of its remediation of print, demonstrated through shared conventions of reading visuals and experiences among readers. However, our overall understanding does not end here because much is left unsaid and comics is an always changing popular culture medium, especially with rising numbers of web comics being created and distributed via the Internet. No matter what changes the future may bring, if we look upon each of these future instances as rhetorical, understood as "A narrative act of persuasion using language and driven by reason and desire" along with its counterpart poetics, then our reading experiences continue being enriched whenever we encounter comics or any related visual narrative.

References

Aristotle. (1987) The Poetics of Aristotle, Trans. Stephen Halliwell, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press

Bolter, J. and Richard Grusin (2000) Remediation: Understanding New Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Eisner, W. (1990) Comics and Sequential Art, Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press

Havelock, E.A. (1986) The Muse Learns to Write, New Haven and London: Yale University Press

Kress, G. and Theo van Leeuwen (2006) Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, New York: Routledge

McCloud, S. (1993) Understanding Comics, New York: HarperPerennial

McCloud, S. (2006) Making Comics, New York: Harper

McLuhan, M. and Quentin Fiore. (1967) The Medium is the Massage, Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press

Ong, W.J. (1982) Orality and Literacy, New York: Routledge