The kids who populate Charles Burns's graphic novel Black Hole are definitely not alright. Sick with what appears to be a sexually-transmitted disease that they call "the bug," an expanding group of teenagers lives in exile from their families and those uninfected students who still attend their high school in suburban Seattle. The ailing teens inhabit a make-shift tent village hidden in the woods near their community, and they subsist mainly on the garbage and occasional charity of the healthy. The disease manifests differently for each of them; many appear monstrous, and when exposed in public the infected are confronted with stares, denunciations, and assaults that impress on them the shameful character of their condition. On the inside covers of the book, Burns includes rows of portraits in the format of a high school yearbook. The clean teens outfitted for photographs inside the front cover reappear in the back in identical clothes and postures but with an assortment of disfiguring symptoms: receded lips that expose a boy's enlarged teeth; jointed appendages that extend like insect legs from a girl's forehead; slim tentacles that droop from every surface of another girl's face; bulbous lesions that coat the face and scalp of a boy who has gone bald, and so on.

Figures 1 & 2 Black Hole © 2005 Charles Burns

Burns and his lurid figures have been prominent among alternative comics artists since the early 1980s when his work appeared in the third issue of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly's influential RAW, a "graphix magazine." He created the cover art for the fourth issue, which includes a chapter of what would become Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic memoir Maus. Compilation volumes of two of Burns's early series, Big Baby: Curse of the Molemen and Hard-Boiled Detective Stories, were published under the RAW One-Shots imprint in 1986 and 1988, respectively. Burns also enjoys a reputation for his work in non-narrative graphic design. His illustrations have appeared in Time and The New Yorker, and he is responsible for the cover illustrations of the journal The Believer, presently in its 55th issue. Black Hole, his best-known work to date, has won Eisner and Ignatz Awards, and The Comics Journal listed it among the "Top 100 English-Language Comics of the Century." In this article, I do not take the space necessary to discuss Burns's novel alongside other recent, prominent graphic narratives of alienated youth such as Daniel Clowes's Ghost World or David Boring, Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, Craig Thompson's Blankets, Gilbert Hernandez's Sloth, Alison Bechdel's Fun Home, or David B's Epileptic, to name just enough to suggest that the comic book of adolescent disaffection may be a genre unto itself. Instead, I concentrate exclusively on how Black Hole's representation of suburban youth culture examines social institutions and cultural norms at work on the imaginations and collective practices of young people just emerging into adulthood. My contribution, then, to this special issue's discussion of the significance of the medium of comics for an array of narrative forms proceeds by way of a demonstration of how Burns crafts a graphic novel of critical force.

In an interview on the release of the novel, Burns explains to journalist Steve Appleford that he "thinks of adolescence as a disease one has to live through," but to regard Black Hole merely as an allegory of the difficulty of teenage identity mutes how the narrative resonates with two crises of public culture: the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the rash of school shootings that became a mainstream media concern in the United States with the events at Columbine High School in 1999. Set in the 1970s prior to the discovery of AIDS but initially published in 12 issues over ten years starting in 1995, Black Hole depicts the cruel consequences of a public that treats a disease as just punishment for the afflicted, and it illustrates how regarding the marginalised and needy as if they are an immoral contagion may reward a community with unmanageable violence. The narrative reaches its ultimate conflict when the vaguely feline Dave Barnes, unrecognizably different from his appearance prior to contracting the bug, goes on a shooting rampage. He kills several infected kids, spits into the mouth of a healthy jock he holds at gunpoint, and returns to his campsite to kill himself and the friend with whom, we learn from their final conversation, he has committed a series of rape-murders. Black Hole presents an uncanny affiliation of a communicable autoimmune deficiency and the gratuitous violence of a community beset by itself.

The gratuitousness of cruelty is its lack of necessity. The public response to diseases such as AIDS or the bug need not regard the affliction to be warranted by moral failure. And to shun those who suffer in order to preserve the integrity of a healthy body politic for which the disease poses no necessary threat is to expunge the vulnerable for the sake of expanding normalcy into exclusive uniformity. More distressing, there can be pleasure in cruelty. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who committed the shootings at Columbine High School, did more than express with unconscionable violence their resentment toward an institutional setting that may have exacerbated and abetted the alienating difficulty of their adolescence. With precision and revelry, they transformed their school into a ritualised killing zone and a calculated media spectacle. Sparing classmate Brooks Brown's life by advising he stay away at the time of the assault, Harris indicated his and Klebold's conviction that nearly everyone else present in the school was a party to the sociality against which they postured, raged, murdered, and finally committed suicide.

In recent essays on the deleterious turns in political culture that have accompanied globalisation, Étienne Balibar has developed a discrimination of cruelties characterised, on one side, by incidents of stunning anonymity, and on the other, by acts of personalised animosity. He names these cruelties "ultra-objective" and "ultra-subjective," respectively (143). Although he acknowledges that cruelty obviously enjoys a storied history, he argues that its novelty at present stems from its increasingly apparent separation from acts of violence committed in the service of an ideal: whether it be the promotion of faith, the extension of sovereignty, the preservation of human rights, or the suppression of some worse violence. Cruelty, Balibar explains, may reward with power those who employ it, but its purpose is not to garner authority. Rather, its purpose is unintelligible to reason (137). His example of objective cruelty is the AIDS crisis as it has taken hold of the Global South and been met with neglect by the nation-states and the multinational pharmaceutical companies of the North. The socioeconomic arrangement in which cost-benefit analyses deem adequate humanitarian assistance impractical treats populations in the millions as superfluous (142). For subjective cruelty, he considers the resurgence of ethnic fundamentalisms that have informed recent genocidal initiatives in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and, at present, the Sudan: all locations in which social violence has been sexualised in acts of collective rape (143). Balibar's categories concern excesses of harm inflicted on large-scale populations, but he identifies a difference between the impersonal administration of life or death health risks and the vitriolic extermination of people as a result of their ostensible differences. He distinguishes cruelty that has no face from cruelty which identifies itself vehemently before effacing its victims. Black Hole, I will suggest, shares in Balibar's taxonomy of faceless and hateful cruelties, but the novel would have us consider how the disease that occasions the former provides the visual medium in which the latter cruelty can be articulated. Teens rendered vulnerable and indistinct by the disfiguring bug confront the persistent risk of being insulted, abused, and even executed because of what others judge them to represent.

My argument develops three related claims about the quality of Burns's contribution to the genre of the graphic novel. First, Black Hole is an intervention in the iconography of AIDS. Like cultural studies scholarship that emerged with AIDS in the 1980s and discerned how the quality of care for PLWAs (persons living with AIDS) would suffer as a result of the stigmas attached to the disease, the novel examines how popular ideas about a disease inform people's experiences of their illnesses as much or more than the brute reality of their physical conditions. Second, by depicting the bug as a disease that apparently infects only heterosexual, middle-class, white teens whose sexual desires correspond to normative expectations, Burns sources the aberrant violence of the community to the frustrations of those teens whose desires are permissible but unrealised or unrewarded. Much of the public discourse surrounding school shootings concerns how places such as Littleton, Colorado, where teens attend Columbine High School, are not supposed to be sites of violence. The presumption that the lifestyle enjoyed by the citizens of these well-to-do places ought to insulate them from cruelty is akin to the privilege accorded whiteness generally. White has been the race of the non-raced, a colour invisible socially because those who possess it have been taken to represent the universal, neutral standard against which are measured the particular experiences of people of colour (Dyer 1997: 1-4). Black Hole depicts whiteness as a visible ethnicity of heterosexual, middle-class existence and then subjects that privilege to the recognition that it affords no surety against a disease that sorts whites into clean and unclean bodies: those who may continue to enjoy the invisibility of their ethnicity in public and those who must hide away their visible, disfigured skins. The novel racialises whiteness not by setting it against other colours but by inventing a difference within whiteness that explodes its presumed neutrality and exposes the artifice of racial identification. Finally, I will conclude with a remark on how the narrative of an epidemic that occasions a massacre becomes, for Burns, the means to develop a graphic narrative of teen disaffection into a meta-critical reflection on visual meaning.

Iconography of the Bug

Heterosexual, middle-class, white Americans do not contract HIV. They do not live with the disease. They do not develop AIDS; and when they finally come to die, they do so in other ways. At least, this is what we have been taught by the iconography of AIDS on display in news media and health agency communiqués since1982 when the disease received its first name, GRID: gay-related immunodeficiency. In "AIDS and Syphilis: The Iconography of Disease," Sander Gilman explores how the inaccurate characterisation of AIDS as a sexually-transmitted rather than a viral disease has informed its iconicity and, by extension, the significance of any individual diagnosed as having the virus (88-90). Following C.S. Pierce, Gilman understands an icon to be "a sign that represents objects through a relationship of similarity, by exemplifying some property associated with the object" (88n4). Whether or not the association of the property with the object has any basis in actuality makes no difference to the efficacy of the icon. For example, the social fiction that AIDS is a gay disease — a fiction diminished of late but powerful in particular regions of the disease's initial flourishing — represents homosexual desire as a source of the epidemic. In turn, the epidemic is taken to express the innate depravity of being gay. The iconography of AIDS, like that of the sexually-transmitted disease syphilis, Gilman demonstrates, tags any particular sufferer with denigrating associations that may not have any bearing on her behaviours, intentions, values, or desires.

In Globalizing AIDS, Cindy Patton recounts how in the late 1980s the World Health Organization produced an epidemiological map of the AIDS pandemic. Three "Patterns" divided AIDS into incidents found among sexually active homosexual men as well as men and women who inject drugs; heterosexually active men and women who do not use drugs; and those populations, primarily in Asia, for which the disease arrived late (xi-xii). Once in circulation, this schema of three patterns changed in significance:

Although the simple scheme of three world patterns may originally have had broad scientific and heuristic value in preparing for a pandemic, it quickly took on a narrative life of its own, offering supranational policy makers and news reporters a veneer of scientific objectivity for what were essentially racist and class-disadvantaging representations of local epidemics. Almost immediately, the pseudoscientific label "African AIDS" circulated with more resonance, and perhaps more credibility, than did the official WHO term, "Pattern Two," to describe the spread of the disease in places where cases related to heterosexual intercourse seemed to predominate. This recycling of very old racist ideas that alleged unchecked sexuality in Africa, or among black people generally, was devastating for local activism in both Africa and North America. (xii)

With Pattern Two tied to black heterosexuals and Pattern One affiliated with white homosexuals as well as drug-users, white heterosexuals were generally encouraged to imagine themselves not immune to the virus but under no systemic risk of infection.

The bug of Black Hole is not identical to AIDS. It strikes only teens and is not lethal in itself. Of course, neither is AIDS; fatalities derive from the way it allows other ailments to affect the body. But no one in Black Hole dies of complications directly related to the bug. Omitted from the single-volume novel are individual yearbook photos and accompanying citations that appear inside the front cover of each of the original 12 issues. The citations look back on the experience of the bug from a time that comes after the resolution of the novel, and several of the statements provide additional information about the affects of the bug and the violence perpetrated by the healthy against the sick. The teen cited on the inside cover of issue 12, for example, explains how his appearance healed and he was able to return to life among the "normal assholes."

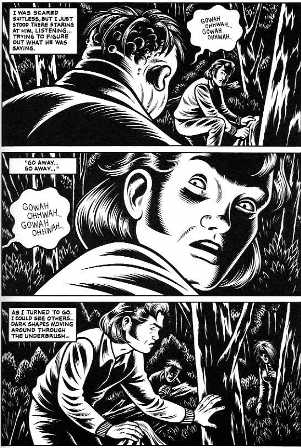

Figure 3 Black Hole #12 © 2004 Charles Burns.

Still, at no point in the narrative proper does the disease just clear up like a bad case of acne and the sick teens believe the bug to be fatal. They conjecture about their impending deaths, and the disease does become an indirect cause for a succession of disappearances later disclosed to us as the victims of the serial rapist-murderer Dave and his accomplice.

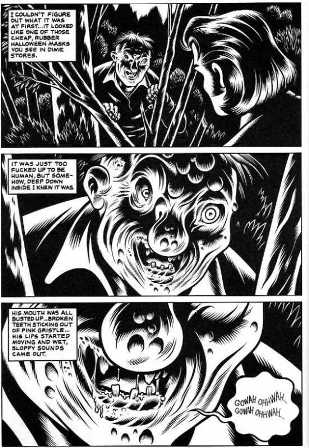

The outbreak is comparable to the emergence of AIDS in the United States because the public believes the bug to indicate a diseased person's moral failing and its physical symptoms inspire disgust and panic. The popular ideas about the bug stigmatise those who become infected with having warranted their affliction. The consequence is that the infected live with their disease but suffer a kind of social death. In the novel's second episode, Planet Xeno, three disease-free young men, including the novel's male protagonist Keith, share a joint in the woods and gossip about how one of them spied a sign of mutation on "Facincani," a classmate who we later learn is Rob, the love interest of the novel's female protagonist. Persuaded that Rob must be infected, one of the three exclaims, "Man … That's the last we'll see of that guy… He's got the bug for sure" (11). At this point, they do not know where the infected go. They only know they disappear. As they traipse through the woods after finishing their joint, they discover a campsite and in it a yearbook that belongs to Rick "The Dick" Holstrum, a young man who has presumably moved into the woods to escape notice after contracting the bug. While the other two rummage through and then needlessly destroy the tent, Keith explores the woods near the campsite and comes face-to-face with a disfigured man. The only hint the man may be Rick is his proximity to the tent and his attempt to ward Keith and the others away from Rick's things.

Figures 4 & 5 Black Hole ©2005 Charles Burns.

This sequence represents well Burns's cinematic aesthetic (18-19). On the left, note how the succession of frames zooms on Keith's perspective of the upper body, face, and mouth of the diseased man. The frame at the top of the next page reverses our orientation. Rick appears in the foreground, but the perspective approximates his view of Keith. The text then zooms in to study Keith's expression from an attitude identical to Rick's. Keith's shock reflects Rick's hideousness. In this encounter, the recognition between the two young men is not mutual. Rick may know his former classmate. Keith does not know whom he faces, but he knows what the man represents: the bug. In the last frame, Keith sees other diseased teens lurking in the woods. He is surrounded by anonymous, mutated figures who cower from his friends and him. Unable to live among the uninfected, these diseased teens have come to live together in the woods. After other kids have seen the last of them, this is where they go.

Although unwelcome in town, they are not truly in exile because they depend for their existence on the garbage and the charity of their former community. Moreover, they are not entirely expelled because they maintain two orders of relation with the uninfected. Some of the diseased, like Rob and later Keith, can conceal their condition and pass among the healthy undetected. With that advantage, they procure food and deliver it to the group in the woods. The other relationship with the community is that of mutual threat. The community of the healthy imagines the communicable disease as if it were both contagious and immoral. According to the citation that appears inside the cover of the ninth volume in the series, healthy teens make sport of tracking down and beating the diseased.

Figure 6 Black Hole #9 © 2001 Charles Burns.

The healthy target the infected not for anything the ill have done but for what they have become. Their offense is ontological; they exist indistinguishably from their disease.

In her review of the Black Hole series, Vanessa Raney also considers the bug a reference to AIDS, a disease she rightly discerns as having a metonymic association with aberrant sexual morality generally (2). She also refers to the bug as a metonym for AIDS, though it is unclear how the disease of Burns's fiction substitutes for AIDS according to the logic of metonymy (33). Instead, what's pertinent about the trope of metonymy is how its economy captures the social logic of the stigmatised disease. To manifest the bug is to cease to be identified as oneself. For the healthy, the meaning of a diseased teen's public appearance is reduced to an instantiation of a single condition: stricken. The bug disfigures some teens beyond all recognition; aside from their status as afflicted, they suffer a most literal anonymity. But even those teens whose physical symptoms do not entirely obscure their prior identity signify a communicable disease believed to pose a singular threat to the health of the community. Any particular carrier signifies the whole disease. Any infected teen may attract vigilantes intent on destroying the bug, though violence can only reach it by harming the bodies of the infected. Even the demise of all those particular bodies would be unlikely to end the whole disease. An appropriate medical response would seek to eliminate the bug from people's bodies. The two social responses related in the novel are instead an attitude of collective neglect that contains the infected on the exterior of the community and the irrational pursuit of their eradication. With this combination, Burns's narrative suggests how the distinct modes of cruelty Balibar defines as objective and subjective can be employed in concert first to neutralise the agency of the ill by rendering them anonymous and then to persecute them with vitriol for a disease they are taken to represent but which they cannot actually embody. The result of such cruelty is not diminished risk of the spread of the bug but instead the perverse satisfaction of demonstrating, albeit falsely, that one's health signifies a substantive rather than an accidental difference from those who have supposedly gotten what they deserve and then some.

AIDS for the Straight

Initiated at a time in which the AIDS crisis in the United States still received considerable media attention, Black Hole nearly replicates the cultural logic that was instructed by the iconography of AIDS in the 1980s. The parallels make all the more striking the location of the bug among heterosexuals in a middle-class white suburb of Seattle. That demographic falls outside the three patterns of the WHO's epidemiological map. Contrary to the iconography of AIDS, the bug associates heterosexual desires among middle-class whites with a mysterious, retroactive impropriety that threatens their community with impurity. A lack of prudence regarding safe sex returns to the infected public shame disproportionate to their behaviour, which barely differs from that of their as yet uninfected peers. In other words, normative sexual desires on the part of young, white, suburban Americans entail the risk of physical deformity, public shame, ostracism, indigence, and, when the infected fail to signify any identity other than that of the disease, social death. With social death comes further vulnerability that allows for the murder and abduction of people who have already disappeared from any social network other than the community of the diseased, a community whose members remark on disappearances but seem unable to do anything other than sit around the campfire and imagine they each might be next. The social dynamic at work as a result of the bug sees normative heterosexuality among white adolescents as a potential formula for an individual's becoming disposable. Even as Burns's tale of the bug portrays a suburban community reorganised by cruelty, it suggests that a bulwark against equity in our social relations at present is an unacknowledged "possessive investment in whiteness." As George Lipsitz defines it, this possessive investment is the systemic regulation for affluent whites of advantages that they have been licensed to regard as just desserts or good fortune but certainly not as the manner in which others are deprived of the same (76). Like racial others unshielded by the unearned asset of whiteness, the diseased teens of Black Hole come to know how one social vulnerability can engender others so that a lack of housing culminates in social ties so negligible that people disappear without being reported as missing.

Burns tempers the bleak scenario of a community undone by disease with a structure of first-person narration by two characters that contract the bug, endure its hardships, survive the shooting spree, and at the end of the novel flee the area. Keith Pearson and Chris Rhodes, male and female protagonists, tell much of the story of Black Hole. Most sections of the novel include textboxes that contain interior monologues by one or the other. Their narrations function like voiceover in film. Early in the novel, their past tense narrations look back from a vantage that we later learn falls within the time of the novel. In the end, their final narrations appear in present tense and reflect the contrasting resolutions of their personal stories. Our last insight into Keith's attitude sees him optimistic about a future with his girlfriend Eliza. Chris's perspective closes the novel in a different tone. Alone after the mysterious disappearance of her boyfriend Rob, she meditates ambiguously about suicide. Restricting to Keith and Chris what James Phelan calls "character narration," Burns attaches our sympathies equally to a man and a woman and through them frames nearly every incident in the narrative within an explicitly heterosexual orientation. Moreover, the novel begins with an admission of Keith's romantic interest in Chris, an interest frustrated for us when an early episode from her perspective focuses on her own love interest, Rob. From the outset, we confront the narrative problem of whether Keith will develop a relationship with Chris, and we contend with the competing narrative concern of Chris's aspirations with Rob. These interests persist until we reach what was the tenth issue in the original series, A Dream Girl. In that episode, the stories of romantic intrigue (in the midst of an epidemic) that dominate the first nine instalments of the novel give way to the realisation that someone has been preying on the infected. The cruel condition of the impersonal bug that undermines identity is trumped in the end by the more grave danger of a serial killer seemingly fixed on those with the disease. The discovery of that crisis forces our character narrators to flee the scene in separate directions.

The first image in the novel is Keith and Chris sitting together in biology class with the body of a frog on a dissection tray between them. In the textboxes of the first several pages, Keith narrates how he experienced what we see in the frames. His thoughts were excited. Luck paired him with his crush Chris Rhodes; "she was a total fox" (2). In what appears to be a classic fit of adolescent social anxiety compounded by disgust at the innards of the frog, Keith stares transfixed at the incision in the frog's belly. His expression and perspiration suggest he may pass out; Chris speaks with concern the novel's first word of dialogue: "Keith?" Keith's narration, however, describes a hallucinatory experience in which the sight of the frog's organs registers like déjà vu and sends him in a vision through the "black hole" of the frog's abdomen into a series of images that foreshadow the events of the narrative that will most concern Chris. A sequence of graphic matches across three frames connects the incision in the frog's abdomen to a cut on the bottom of a foot and then to a wound running the length of a woman's spine, which is how the bug will manifest for Chris. A fourth frame of identical dimensions shows the back of a hand covering a person's genitalia. The wound imagery of the preceding frames dictates that the hand hides a vagina, and that image triggers Keith's further disorientation until he blacks out and collapses to the floor.

The Freudian subtext of Keith's hallucination is obvious. The appearance of the vagina in a series of wounds promotes anxiety about castration. And the novel is rife with imagery that suggests repressed illicit desires are making their way from Keith's unconscious into his dreams and visions. However, Chris's dreams complicate the overstated Freudian subtext that informs our relationship to Keith's point of view. The dream sequences of each protagonist reinforce the heterosexual iconicity of the bug. The visions reflect how each of them relates to his or her disease. He sees wounds that literalise into vaginas; she sees serpentine imagery in combination with penises. While Burns seems intent on his character narrators working out in dreams the repressive stresses that are typical of their age but more pronounced for them as a result of the bug, he is not so beholden to Freudian themes that he imposes on Chris's imagination that most reactionary of Freud's conceits, penis envy. Her wants do not appear to be born out of that Freudian psychopathology of lack; rather, to put it plainly, she likes and desires men. Specifically, she wants Rob, and in her recollection of their first sexual encounter we see that she had, for a time, an unembarrassed excitement about his anatomy.

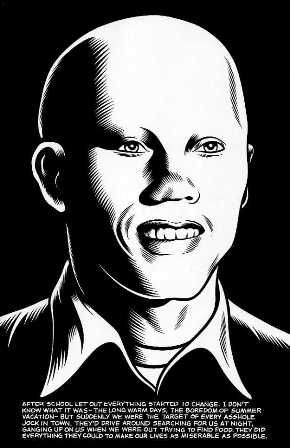

Chris contracts the bug from Rob when they sneak away from a house party and have sex in the middle of a graveyard. We learn of the episode when she reflects a week later on how sex with him began with such promise and then went irreversibly wrong. Her voiceover recollection emphasises her sense of agency interacting with Rob, and we witness events in a flashback marked, like the novel's dream sequences, in frames edged with wavy lines. Chris spied Rob at the party and felt a draw to him that made her abandon her usual shyness. When they slipped outside the party for a smoke, she suggested they take along a bottle of wine, and then she suggested that they not return to the party. She decided they should go to the cemetery. She led them to the bench, and she initiated their kissing. When Rob interrupts to say "there's something I should tell you," she says "shh…I know… I know" before he can say anything else (43). It never becomes clear what knowledge Chris believes she is claiming, but she certainly does not know that Rob has the bug. For the 24 ensuing frames, we witness Chris and Rob's foreplay. They do not speak. We see their faces close together, his hands on her hips, her arms clutched around his shoulders above her, her hair splayed onto the grass with his hand alongside her, and so on. In each frame, Chris's narration reports how aroused she was and how she felt in command: how she pulled him "onto the damp grass" (45). And when they shift from foreplay to intercourse, she describes how easy it was to pull down her own pants, help him with his, and begin.

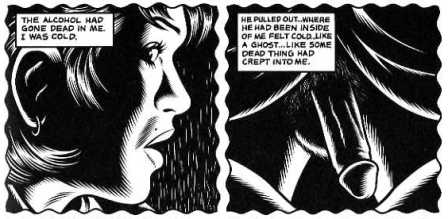

Figure 7 Black Hole © 2005 Charles Burns

Her sense of control ends abruptly when the silence between them is broken not by either of them but by a tiny mouth on Rob's neck. A manifestation of the bug, the tiny mouth is usually hidden beneath Rob's collar, which is how he is able to pass between the communities of the healthy and the diseased. But as the novel unfolds, his second mouth becomes increasingly articulate. As he sleeps alongside Chris several days after their first time, the mouth admits insecurities Rob feels but will not admit about the new relationship. "It won't work," the mouth says repeatedly until the distressed Chris struggles to wake him (183). In the first sexual experience between Rob and Chris, the mouth's inarticulate groan of pleasure at the moment he climaxes alerts them to what Rob has failed to say and Chris has not heard. He has the bug. Soon, she will too.

Figure 8 Black Hole © 2005 Charles Burns

Her narration teaches us that his penis, which had been "just right," took on a deathly significance. The juxtaposition of these consecutive frames amplifies how it was suddenly unpleasant, yet hints at how Chris will retain an attachment to Rob in spite of the awful miscommunication with which they begin their sexual relationship. Taken by itself, the left frame shows Chris in profile looking askance at Rob above her. Her eyes are on him, but she turns her head away. Relative to the right frame, the same sideways look at Rob shows Chris turned toward but averting her eyes from his penis. The ambivalence expressed between these two frames articulates the rift in sexuality brought about by the potential insinuation of the bug into every physical encounter.

Chris's narration makes apparent her feelings for Rob and her excitement about having sex with him. Her emphasis on how she felt empowered in the encounter up to the moment she discovers his second mouth also gives us an insight into her best expectations for sexuality as a young heterosexual woman. The autonomy she values and believes possible in a relationship of mutual regard is hard to come by for the young women of Black Hole. For women such as Chris and Eliza, whose disfigurement from the bug does not disguise entirely their sex or impede how other people perceive their genders, two stigmas attach. Like the infected men, they represent the bug metonymically; unlike the men, the appearance of the bug also marks them as sexually experienced and, presumably, available.

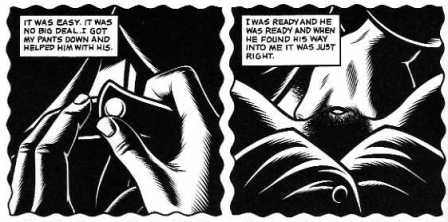

Different from Chris, Keith risks infection wilfully. He has sex with Eliza, and everyone knows she has the bug. Her tail gives it away. It resembles that of a lizard. As Keith learns during sex, it even breaks off and, she assures him, regenerates. His narrative of this first sexual experience of his life suggests that the pressure of his virginity impinges on him more than does the threat of a disease that everyone seems to be catching anyway, including Chris, the woman he aspires to love. The feeling of incredulity he relates having at the moment Eliza guided him inside her conveys his investment in having sex for the first time: "And that was it… I couldn't believe it. We were fucking" (216). The heterosexual framework Burns constructs with his two character narrators does not equate Chris's and Keith's attitudes toward sexuality. She aims for sex that will affirm and not compromise her autonomy. He thinks of sex as something to accomplish. The differences between them represent how middle-class young women and men negotiating the precarious initiation into sexual activity confront quite different mores and expectations that shape how they understand what it means to have good sex. By good, I mean to refer both to mutual pleasure and to an experience that affirms each partner's well-being.

I have recounted select, decisive episodes in the narratives of Keith and Chris because they corroborate my contention that Burns's technique of character narration provides a heterosexual framework through which we examine what happens to social relations in the novel as a result of the bug. The double character narration commits the book to heterosexuality but does not bias the implicit stance of the reader toward a masculine or feminine perspective. "Character narration" does not account, however, for the entirety of narration in Black Hole. Critical events take place without Keith's or Chris's attitudes focusing our understanding of what has happened. In the landmark Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, Gèrard Genette refers to a schema of three kinds of "focalization" to explain how narratives regulate what readers see in a story (189-194). For example, the insight afforded us by the moods and intentions of the character narrators Keith and Chris results from "internal focalizations". Passages that reveal to us how Dave is a rapist and murderer have "external focalization"; we see the behaviours of characters without access to their intentions. (Incidentally, a text in which the narrator sees and knows more than any character uses "zero focalization".) Since Genette introduced his terminology, the field of narratology has conducted a rich and contentious debate over how best to account for the way narratives shape a reader's perspective. Whatever modifications or objections to Genette's work on "focalization" have been influential, visual metaphors have remained prominent in the nomenclature of the field. The ocular rhetoric integral to narrative theory would seem to suggest that literary studies need only lean more intensely on narratology in order to take up the recent outpouring of provocative, brilliant graphic narratives that are the occasion for this special issue of Scan. However, because narrative theory's various notions of "focalization" translate the workings of a linguistic text into visual metaphors that characterise our orientation toward a story, accounting for how in comic books actual pictures inform our stance requires that we supplement any theory of narrative "focalization" with an attention to how images engender meaning differently from words. For even in episodes of "internal focalization", in the medium of comics we may, and frequently do, view frames that include an image of the character narrator within the picture described by her or his voiceover. When visual cues exceed the character narrator's account of what she sees, the discontinuity allows us to discern not just potential unreliability in the narration but also evidence that invites us to interpret the scene otherwise.

To this point, I have deliberately avoided any mention of debates over the literary merits of graphic novels. An impressive, growing body of scholarship on the history and form of comic books has already settled the matter in academia, as the routine inclusion of graphic narrative courses in the curricula of literature departments makes apparent. However, we are still in the mopping up phase of the paradigm shift that has made comics a credible subject for research and teaching. What remains in question is what further changes to the disciplinary practices of literary study will be required for us to contend programmatically with texts in which narrative works through the interplay of words and pictures.

Gaze Narration

In addition to the modes of narration they share with traditional, non-pictorial texts, graphic novels narrate with the composition of frames. What we see always comes at an angle that informs our attitude. Film studies typically refers to this narrative technique in terms of the camera's "gaze," and following Laura Mulvey's influential "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" has been especially attentive to how a gaze may be heterosexual and masculinist. Mainstream narrative cinema, Mulvey argues, represents woman as an "erotic object for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium" (11). The composition of shots, in other words, routinely positions men and women spectators as subjects of heterosexual masculine desire looking at women as erotic objects in their relations with other characters and with the audience. Widely anthologised and typically required reading in courses surveying the history of film theory, Mulvey's essay has also been roundly criticised for overreaching. If it is more fair to say of many films what Mulvey would seem to suggest of film tout court, it is also arguably the case that her suspicions about the irreducible masculinism of the camera's gaze do at least inform how current feminist film criticism investigates the gender politics implicit in any film's cinematography. Burns's cinematic style of comics invites our interest in the gender of his gazes, especially in episodes of "external focalization".

Black Hole represents the objectification of women through references to pornography. In two episodes, we see pornographic magazines in spaces inhabited by men who perpetrate sexual violence against women. Just before having sex for the first time, Keith slips into the bathroom of the house where Eliza rents a room from a group of slightly older men and sees a cache of magazines that make him wonder how she can stand living in a "cruddy" place with a "bunch of burned out college dudes" (209). The college dudes, she later tells Keith, gang-raped her during a party. Porn is also strewn around the campsite of Dave and his accomplice Rick (not Rick Holstrum). A sequence with external focalization late in the novel concludes with Dave shooting the unsuspecting Rick through the head and then killing himself. Just before Dave enters the scene, we zoom on an image from a magazine of an impassioned naked woman pressing her breast up to meet her own outstretched tongue. The woman's pose communicates that she also sees her body as an object to be consumed. The isolated shots of women depicted as sex objects thematise within the narrative the masculinist gaze. They also serve to distinguish a predatory manner of looking at images of women from how we look at the images of Black Hole. I do not mean to suggest that the novel indicates a causal relationship between consuming pornography and perpetrating violence against women. Rather, the novel makes the more subtle observation that the men who perpetrate sexual violence against women, whether in that criminal moment or as a matter of permanent disposition, fail to see them in any way other than as they are depicted by the masculinist gaze of pornography.

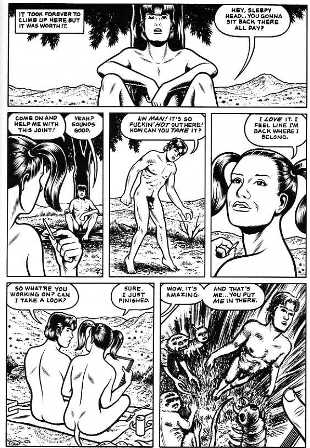

When we look at naked bodies in the novel that are not citations of lewd nudity from magazines, we gaze at men and women. We have already seen how Chris's first sexual encounter with Rob shows us her attitudes toward his penis. In a sequence from the day after Keith has stumbled across the carnage of several infected teens shot dead by Dave, Keith and Eliza appear to be picnicking naked in a remote location, presumably after sex. They have pledged to make a life together someplace far south of Seattle, and they have stopped en route to camp. As they rest, Eliza sketches.

Figure 9 Black Hole © 2005 Charles Burns

Like the citations from pornography, Eliza's drawing of Keith contrasts with the composition of bodies in the novel. She depicts an idealized Keith transcending bug-like personifications of the disease the couple shares. The full frontal shot of Keith at the centre of the page shows him on tiptoes complaining about the hot ground; the slender tentacles of the bug, absent in Eliza's sketch, can be seen against his ribs. Her romantic attitude is understandable. The two have become caring lovers, and their relationship has inspired her to draw again. As they sit with the drawing and share a joint, she is able to explain that she had abandoned her dream of becoming an artist after the "college dudes" decided her sketches, studies of the bug, meant she was "into some freaky shit" (310). A conflict over the drawings escalated until they raped and beat her unconscious. She tells Keith, "I woke sore between my legs…sore all over. They'd written things on me…all kinds of nasty, ugly stuff" (311). In a gesture that exhibits how the bug helps to occasion cruelty, the rapists also wrote on her bedroom door "I am the lizard queen and I can do anything" (204). The sobering irony of the line is that these men demonstrate the willingness to do anything to Eliza without regard for her person. Her sketches were an obvious effort to deal with her disease, to establish her autonomy over a condition that causes others to see her as reptilian instead of human. Her attackers opt to look at her artistry not as evidence of Eliza's self-possession, but as an excuse for their misogyny. They take the appearance of the bug to endorse her mistreatment. Presenting the assault as a flashback Eliza narrates to Keith, Burns confines the episode between images of the naked couple sitting side-by-side in a posture of mutual regard. We view them as they look at each other.

Complementary to the double character narration, the framing of our gaze emphasises that relations in the novel are heterosexual. Sexual desire only appears between men and women. Queer desire is not even a minority position on the margins of the narrative. Rather than constitute a neglect that would invalidate queer desire, this omission ensures that the stigma attached to the bug divides heterosexual desire from within. Identical wants result in some teens diseased and outcast while others remain well and aligned inside the suburban community. With the chance dynamic of that division revealed, Burns's graphic novel brings critical attention to the artifice through which some desires (e.g. queer desire) become characterised unjustifiably as less natural than others. He manages to draw on a cinematic aesthetic to relate a narrative of straight desire and its critique while avoiding the kind of masculinist gaze his text urges us to indict.

Seeing White, Men and Violence

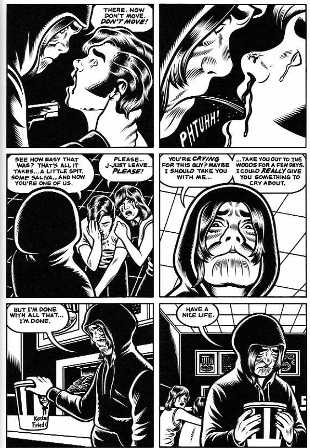

One reward of the heterosexual orientations of Black Hole is that when the narrative erupts in violence we can see more readily the relationship between norms of masculinity and misogynist cruelty. Men are the exclusive perpetrators of the novel's white on white violence. A confrontation in line at Kentucky Fried Chicken between the infected Dave and a healthy, athletic young man reiterates the shame aimed in public at the diseased and discloses abruptly the extent of Dave's cruelty. When the "jock" scolds Dave for frightening the young woman at the register and declares that "nobody wants you here," Dave pulls a gun, which is our first decisive clue that he is responsible for the dead bodies discovered a few pages earlier by Keith. Dave does more than wield his gun to dispel the other man's threats or even just to secure his order of chicken, which he will deliver as a last meal to the soon-to-be-murdered Rick. He uses the power the gun affords him to humiliate the other young man and to threaten him with contamination. We do not know if passing saliva spreads the bug. It seems doubtful, but the young man's fear of infection is palpable in his expression as Dave spits in his mouth. Later, we'll learn from Chris's final voiceover that Dave told her how at school he was beaten up almost every day by men like this athlete (340). Shamefully, he seeks to vindicate himself by appropriating the machismo wielded against him in school. With the gun and the bug, he is able to seize masculine advantage over the more able-bodied young man and then to bully him. However, attaining masculine authority to rival that of the men who abused him means that Dave shares not only in their violence but in their disdain for how he still does not measure up to the normative requirements of late adolescent masculinity. The bug makes him a potent social threat yet renders him a permanent exception to normalcy. In other words, he seems a likely recipe for a "school shooter," and at KFC we see how his contemporaries may be implicated in his development.

Figure 10 Black Hole © 2005 Charles Burns

The middle two frames again replicate the reverse shot technique of filmmaking. From an angle comparable to Dave's, we see the bloodied man and the crying woman on the floor. Dave tells the man "A little spit. Some saliva… And now you're one of us." When we look up at him from their position, his statement to the woman revises our understanding of what we have read in the novel to this point. He threatens to take her into the woods and "really" give her "something to cry about", but then acknowledges in the bottom left frame that he is "done with all that" (289). The conflict at KFC demonstrates the substantial animosity directed at the bug by the healthy, and Dave's resentment toward that public scorn makes sense. But his reaction is cruel. He terrorises the couple, and he betrays that he has been doing much worse. Even while living as one of them, he has preyed systematically on the diseased teens that have lost their place in the suburban community. Dave is "done with all that" because he has come to KFC immediately after murdering several diseased teens as they slept. Soon after this confrontation with the jock, we understand that at KFC he was already intending to commit suicide.

The provocation for the change from surreptitious rape-murders to a spontaneous shooting spree that will end in suicide is Chris Rhodes's rejection of his profession of love. When Dave returns to his campsite with the bucket of chicken, we finally realise that he arranged Rob's murder in the hope he could then win Chris. Wary of Dave after he has tried to kiss her, Chris has run away from the house where she and several others had found temporary shelter. When she flees from him with an aversion similar to the repulsion expressed at the sight of him by the uninfected, Dave exacts revenge on everyone at hand who shares his condition. The vexed character of Dave's self-loathing is most apparent when he commits suicide. With a scolding contempt, he points the gun to his head and, echoing Nike's ubiquitous commercial slogan, coaches himself finally to "just do it." He should have done it "long ago," he explains to himself, but did not because he is "so stupid… since the day you were born, stupid little fuck" (292). Dave's suicide exemplifies the pernicious logic of the social response to the bug. He draws on his best masculine ethic to put the gun to the head of a "stupid," diseased boy who, he believes, deserves to die. With an efficiency that his repeated acts of misogynist violence cannot match, he finally demonstrates that he is tough enough to eradicate the failure of normative masculinity he represents.

Dave's last act embodies how in Black Hole the impersonal character of the bug elicits hateful cruelty in the face of which the infected can typically only survive by disguise or flight. This collaboration between the objective and subjective responses to the bug ensures the violent expulsion of the diseased from the community. That expulsion might be construed as an exacting service to the ideal of a healthy populace plagued by an emergency were the removal of the ill not premised on the gratuitous construal of the bug as in itself an act of subversive violence. Recall that Balibar explains the unnecessary character of cruelty in terms of its distance from the kinds of ideals typically invoked to legitimate violence. When the jock proposes to Dave that his presence upsets the people at KFC, he means that they regard the intrusion of the bug as a threat to their welfare. But as we have seen, Dave's threat comes not from his disease but from his emulation of the jock's masculinist bravado, that same bravado with which he cajoles himself to suicide. The objective demeanour of the community toward a facile demographic of us and them enables cruelty in the service of an unprincipled idea of difference whose invention is already an act of symbolic violence that attributes to the infected an inhuman agency.

Conclusion: Mean Visuals

My argument has admired how Black Hole remarks on the dominant cultural responses to AIDS and school shootings in the United States. Bringing these concerns together in the narrative allows Burns to suggest that normative, white, masculine, middle-class heterosexuality is possessed of a cruelty that informs the stories that have circulated most readily in public about these two crises. To conclude, I want to introduce the further observation that by presenting his critique in the medium of sequential comics Burns invites us to reflect on how visual meaning operates socially. Nothing would preclude an exclusively linguistic version of Black Hole from relating how the unconventional appearance of people with the bug mobilises healthy teens to keep up appearances by depriving the infected of public space. A non-pictorial text could assuredly describe how the very few inhabitants of the woods who manage to retain tenuous relations with healthy teens do so either secretly or by passing as uninfected. But a Black Hole without pictures would lack the novel's self-reflexive attention to the prospective hazards of visual meaning.

In the normative environment of their Seattle suburb, the metonymic association of each diseased teen with the whole bug denudes them of individual and human identity. Their dispossession signals the priority the community assigns to what is seen over what is said. Witness to the narrations of Keith and Chris, we recognise the discontinuity between how the infected characters verbalise their alienating experience of the disease and how the uninfected react affectively to the bug's visual appearance. The practical consequence of the suburban community's commitment to the visual over the verbal is that the interface between the healthy and the sick is not discursive; the community divides prior to any discussion of what the disease might mean on all sides. The affective reactions to signs of the bug split the community into sanitary insiders and contagious outsiders, which is to say that visceral responses to disfigurement persuade attitudes toward the infected that precede and inform the interpretation of the bug as a sign of moral failing and public threat. The novel's reflection on the relationship between visual and verbal meaning, then, complicates Burns's narrative critique of straight white masculinity by hinting at how a discursive account of damaging ideology may fail to discourage the visual appeal of images. A cautionary tale about the fallacies of reading a disease as immoral and straight white masculine privilege as natural, Black Hole also invites us to recognise the difficulty of explaining away meanings inspired by a look. If it makes sense then to contend against visual meaning as Eliza does with other pictures, we must also concede that the address to affect of contentious visual rhetorics curtails deliberation.

References

Appleford, S. (2006) "Charles Burns." Los Angeles City Beat, 141 (February 16, 2006) http://www.lacitybeat.com/, accessed March 1, 2008.

Balibar, É. (2002) Politics and the Other Scene, London and New York: Verso.

Burns, C. (2005) Black Hole, New York: Pantheon.

_____ (2001) Black Hole #9, Seattle: Fantagraphics.

_____ (2004) Black Hole #12, Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Dyer, R. (1997) White, London and New York: Routledge.

Genette, G. (1980) Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, Jane E. Lewin, trans, Ithaca: Cornell UP.

Gilman, S.L. (1987) "AIDS and Syphilis: The Iconography of Disease", October, 43, Winter.

Lipsitz, G. (2005) "The Possessive Investment in Whiteness" in P. S. Rothenberg (ed.) White Privilege: Essential Readings on the Other Side of Racism, New York: Worth Publishers.

Mulvey, L. (1975) "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema", Screen, vol. 16. No. 3, Autumn.

Patton, C. (2002) Globalizing Aids, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Phelan, J. (2005) Living to Tell About It: A Rhetoric and Ethics of Character Narration, Ithaca: Cornell UP.

Raney, V. (2005) "Review of Charles Burns' Black Hole", ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 2.1, http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v2_1/reviews/raney.shtml, accessed May 13, 2008.