The question of scale presents as a key challenge for contemporary screen media, with the migration of the moving image across new networks, platforms and devices. The issue of scale is not only relevant for the emerging screens of mobile media but also for the future of the long-form narrative feature in the digital age. The feature form is not exempt from recent shifts in the screenscape marked by increasing levels of media hybridity, fragmentation and excess. In this context, screen scale for the feature form is taken as: the scale (or extent) of narrative structure and the scale (or size) of the moving image itself. This article seeks to highlight new and creative responses to the challenge of screen scale, in particular those that reveal innovation in feature film narration, scriptwriting and production.

The title of this article has been lifted from Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau’s S,M,L,XL (1995). This book, described by its authors as a ‘novel’ on architecture, presents a manifesto of design, form and aesthetics for the late-twentieth century. For this discussion on new feature film, S,M,L,XL is appropriated for its structure (albeit on a micro-scale) together with Koolhaas’ general emphasis in scale, as a key quantity and driving force of contemporary form and aesthetics. While S,M,L,XL may also be relevant to other new screen media (particularly the urban screen), this is beyond the scope of this research. The intent of this article is to highlight new directions for the feature form using a sample of case-study feature films: from [S] to [XL]. The films selected do not amount to an exhaustive study, rather a rapid ‘fly-over’ of the feature film screenscape from 2005-2008.

Figure 1: Diagram of Comparitive Screen Scale (to scale)

This diagram is a scale drawing of comparative screen size: from the Small [S] screens (of YouTube); to the Medium [M] screens (of the ubiquitous home widescreen); to the Large [L] screens (of art house cinemas and film festivals) and the Extra-Large [XL] screens (of the multiplex and megaplex). This is, in one sense a polemical diagram – since it negates the position of the spectator in relation to the screen. However, it does portray the extent and variation in the quantity of screen scale across the contemporary screenscape.

[ S ]

Four Eyed Monsters (FEM) is a recent film by Arin Crumley and Susan Buice. It has received considerable attention as the first feature film to be (legally) distributed on YouTube. The FEM project is (all at once): an underground/independent American feature on the festival circuit (which premiered at Slamdance); a 71-minute YouTube clip; a DVD (with added extras) and a website featuring an online documentary, presented in 8 episodes and 60 minutes of vlogs. FEM also has its Web 2.0 incarnations: on MySpace TV, FaceBook and Flickr.

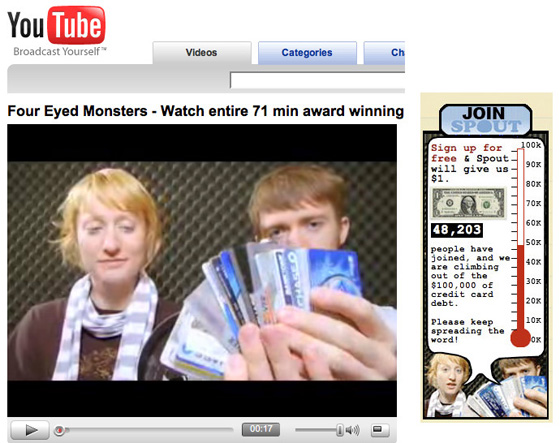

Figure 2: Online distribution matrix of FEM

This is a screen grab from the FEM website. It shows the roll-out of the film across the screenscape. And it’s all for sale: as a portable download for your i-Pod; a ‘max’ download for Apple TV; a DVD mail order; a poster or perhaps a T-Shirt, in either black or white. All FEM digital downloads are Digital Rights Management (DRM) free – so the film can also be screened to an audience, provided that 50% of the proceeds are returned to the filmmakers via PayPal. The entire film was also released free to view at MySpace TV and YouTube. These versions include a prologue from Crumley and Buice who tell the story of their $100,000 (USD) debt incurred in the making of FEM over a period of 14 months. This figure includes approximately $55,000 racked up over seven credit cards (Lyons 2005).

To alleviate this debt, the young filmmakers cut a promotional deal with the online film portal Spout.com, who pledged to give them one dollar (USD) for each new member they attract. Spout is a website sustained by DVD sales that seeks to promote independent film culture. The FEM case works as a sponsorship deal: FEM is financially rewarded for directing people to join Spout (there is no fee for the new members who join up). The FEM filmmakers have additionally sold approximately 1,500 DVDs together with 350 digital downloads of the film (Crumley 2007). In the process of writing this article, FEM has switched sponsors from Spout.com to OurStage.com, in what appears to be a similar deal. For independent film, this represents a trajectory from the [L] festival screen towards the [S] screens of online and viral marketing. For the filmmakers, the strategy has worked well to date: the FEM website in April 2008 notes that $50, 000 has been raised. This online momentum has also gained FEM an IFC TV (Independent Film Channel) television premiere and a DVD exclusive ‘re-release’ at Borders.

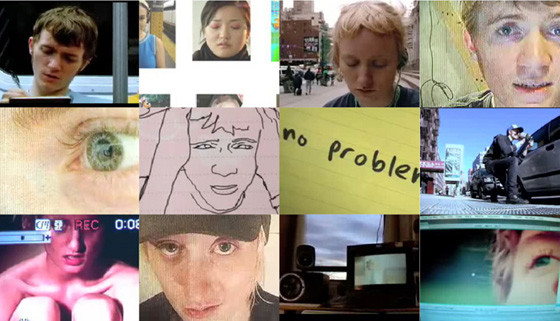

Figure 3: Arin Crumley & Susan Buice on YouTube

FEM has propelled the feature film into the labyrinthine world of online video and social networking. It is an innovative case study of self-distribution. By December 2007 FEM notched up close to a million views on YouTube as a 71-minute ‘clip’ - a very respectable audience for any small, independent feature. Since the news of the IFC premier and the Borders DVD re-release, FEM has disappeared from YouTube and MySpace TV. Some extracts remain but the “entire 71 min award winning film” on YouTube is gone. In Sydney FEM screened at the Destination Film Festival where Arin Crumley participated, live via satellite from New York on the ‘Cyber-Born Film’ panel. This presents a good example of the crossover of the film: from the [S] YouTube screen back to the [L] festival screen, and presents a chance to situate the question of screen scale for FEM.

Figure 4: A matrix of stills from FEM

In terms of both narrative and aesthetics, FEM reflects the fragmentation of the screenscape itself. The narrative, partly autobiographical, dissects the lives of its twenty-something filmmakers, Crumley and Buice. It is a hybrid narrative: part melodrama, part documentary and part road movie. FEM restages the trajectory of its filmmakers’ real world relationship: from their meeting on an internet dating site, the ensuing romance, their break-up and reconciliation. As a new narrative it represents the ‘mutlimedia-isation’ of romance and dating in the digital age. In the film, communication (traditionally as screen dialogue) is superseded by an array of competing new media, in the form of sms text messages, emails and social networking websites. Communication is a key theme of the film, and the story of FEM is also told through ‘old media’ in the form of an exchange of on screen Post-It notes between Crumley and Buice. Megan Spencer, curator of DestFest 2007, describes FEM as “a delicate pop fusion of art, design, narrative filmmaking and digital style” (2007).

In FEM, the new media screens themselves are key ‘characters’: the DV cam, web-cam, phone-cam, pc-screen, tv screen and i-Pod all compete for screen time. And here, the ‘participatory culture’ of Henry Jenkins (2006) is folded into a feature film narrative. FEM is a project that works well at the [S] scale: on YouTube and as portable downloads for mobile media. Current research on micromedia suggest that the [S] screen is a “visual space with its own characteristics and limitations” and one where “wide shots, pans, surround sound, mood lighting and anything with too much detail is almost no go” (Pierce 2005). And FEM gets this right. It works with a considered range of shot sizes, with a majority of Medium Shots (MS), Close-Ups (CU) and Extreme-Close Ups (XCU). The film exploits the entire suite of digital image-capture tools. This results in an excess of vision and multi-screen frames (an example of ‘digital style’) that has been dubbed the “desktop aesthetic” by screen theorist Holly Willis (2005: 39). In this sense FEM really does deliver a new kind of feature film, one that adopts a multimedia language and aesthetic. FEM is also an example of the new “cinema of complexity” where “supplementary-ness” (in this case the associated Web 2.0 sites, vlogs and blogs) allows “for an increasingly complex relationship with the core film” (Harper 2005: 99).

The transition of FEM to the [L] film festival screen raises a new set of questions on screen scale – particularly about its relationship to ‘film’ and film culture. In the US, FilmMaker magazine includes FEM as part of the recent “mumblecore” independent film movement:

If we’re going to generalize, we might say that generally these films are severely naturalistic portraits of the life and loves of artistic twentysomethings. The genre’s ultra-casual, low-fi style has been simmering for the last decade, made possible by the accessibility of DV and inspired as much by reality shows and YouTube confessionals as by earlier American independent cinema. (Van Couvering 2007)

Mumblecore has attracted the descriptors “Slackavetes” (after John Cassavetes) and “neo-slackers” (after Richard Linklater). In the first comparison to the pioneer of American independent cinema there is an interesting parallel. In the late 1950s Cassavetes gained his cash start-up for his debut feature Shadows (1959) on a radio show. On air he said: “wouldn’t it be terrific if just people could make movies instead of all these Hollywood bigwigs who are only interested in business and how much the picture was going to gross and everything” (Cassavetes in Gaspard 2006: 97). In response two thousand listeners donated one dollar each towards the project. Jump-cut to 2008, almost fifty years later, Arin Crumley speaks at the Destination Film Festival about new models of ‘subscription based’ financing and distribution (Crumley 2007). In contrast, a comparison of the Mumblecore filmmakers to the preceding wave of Gen-X no-budget filmmakers is deceptive. The 1990s guerrilla filmmakers were a band of film-geek obsessives, armed with an intimate knowledge of the cinema. In the case of Richard Linklater, Slacker (1991) is seen as homage to a range of international Art Cinema:

His inspiration came from Max Ophüls’ La Ronde and Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. You’ll find Michelangelo Antonioni and Rainer Werner Fassbinder one-sheets on his walls, and he’d much rather talk about Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac than either Jaws or The Brady Bunch. In short, he is a self-trained art-film brat of the highest order. (Pierson 2004)

With FEM, the ‘neo-slackers’ (Crumley and Buice) have moved beyond postmodern intertextuality, and perhaps celluloid film culture altogether, towards a new mode of digital cinema. In one telling scene of FEM, the filmmakers stand in their inner city studio surrounded by a wall of mini-DV tapes of their project. In one interview, Crumley accounts for 225 hours of material shot for the film (Cole 2006). In comparison to low-budget, celluloid film production, this represents a colossal shooting ratio - somewhere in the order of 160:1. And, in contrast to Linklater’s long Ophüls inspired celluloid takes, in FEM it is the post production phase of filmmaking (and editing in particular) that becomes the key site of creativity. For Holly Willis, this is a trend of new digital cinemas:

…experimental feature filmmaking is often not so much concerned with ‘shooting’ as with ‘capturing’; it is less about creating pristine images of perfectly orchestrated and highly composed events and more about collecting a body of materials that will then be manipulated extensively, pixel by pixel if necessary (2005: 35).

An alternative way to situate FEM outside of ‘Indie’ cinema is in relation to the ‘Digital Storytelling’ movement on the web. This is a distinct mode of digital media production which (like FEM) is also an autobiographical, microbudget and DIY form of moving image media. The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) describe Digital Storytelling as “the telling of a personal story using multimedia tools” through a combination of “audio visual resources of their personal archives (photographs, video footage, text, music and sound) to produce a 3-4 minute personal story which they then narrate” (ACMI 2007). In the US, the Center for Digital Storytelling works along similar lines. The micro-movies of digital storytelling are specifically designed for the [S] screen, in the form of short clips as an assemblage of still and moving images, graphics, titles, music and voiceover narration. To a degree, FEM fits this model: in terms of its autobiographical content, digital style, use of voiceover narration and its media hybridity (a mix of video, still images, typographics and hand-drawn animation). However, in terms of its narrative scale, FEM is stretched to an 85-minute feature – a kind of ‘supersized’ Digital Storytelling clip.

Figure 5: ‘Digital Storytelling’ at ACMI

With this comparison to Digital Storytelling, the commitment to the long-form feature length taken by FEM reads as conservative: an anomaly measured against its many other innovations. A reconsideration of FEM as modular cinematic form (a ‘feature’ narrative divided by episodes, chapters or tableaux) would certainly be an interesting proposition in the age of clip-culture and YouTube. The potential to dismantle feature form as new narrative to operate across the screen scale, represents a creative opportunity for new digital cinema. This would bring the feature film in proximity to the emerging field of ‘cross-media’ production, defined as “a media property, service, story or experience distributed across media platforms using a variety of media forms” (Wikipedia). A recent cross-media project from the US is Quarterlife: an online drama played in 8-minute webisodes. This is another narrative, like FEM, based on twenty-something creative types coming of age in the digital world. The web series was purchased by NBC for late night television broadcast. This marked a bold strategy – to shift work across the screen scale: from [S] to [M]. However, the transition proved to be a ‘disaster’ – a reinforcement of the conservative grip network television holds on media form:

Apparently the guilty pleasure of watching twenty-something whiners on the Web doesn't translate to that other small screen. NBC's TV debut of quarterlife, which has been running for weeks as a Web-only on its own quarterlife.com as well as on MySpaceTV, was an unmitigated disaster. The Hollywood Reporter says the ratings were the worst the network has had in the 10:00 PM time slot on a Tuesday in 17 years (Griffith 2008).

In Australia, writer/producer Chris Corbett has recently produced a cross-media project called TinyTown – webisodes for kids. TinyTown has been designed for the [S] YouTube screen and works in shorter webisodes than Quarterlife. On this, Corbett says: “I thought 8 minutes is too long. So I'd say ideally the length of an episode would be between 4 and 5 minutes” (Media Report 2007). Corbett is operating at the [S] scale of the web, as a cost-effective way to pilot TinyTown for consideration for the [M] television scale. In the wake of Quarterlife this success of TinyTown will be interesting to follow.

Figure 6: Quarterlife as Cross-Media: Webisode 1

To conclude this first section of the article, FEM is an innovative project, particularly with regard to online self-distribution, marketing and promotion. At the same time, the project reveals a (somewhat paradoxical) nostalgia for the long-form feature film. Screen theorist J.J. Murphy notes this on his screen blog, when he writes on FEM: “When asked what he would do if he had another film, Crumley somewhat surprisingly indicates that he would submit it to Sundance” (2007). So, above the dizzying hype of Web 2.0 there is evidence that the ambition for that [L] cinema screen, illuminated by a beam of light for a silent audience, persists. It is also apparent that the identity of being a ‘filmmaker’ making ‘films’ - remains central for the new creative generation. In reality, this will remain an elusive goal. Independent film writer Geoff King points out that applications for Sundance film festival (where FEM was initially rejected) rose from 840 films in 1999 to a staggering 2, 426 films by 2004 (2005: 38). Furthermore, in the field of media education, Banks and Seiter (USC School of Cinematic Arts) observe the lure of the big screen:

The easy availability of desktop video production coupled with distribution through YouTube and Facebook has increased the ranks of students aspiring to be Hollywood directors. Enrolments in production courses and applications for film school are booming: at the USC School of Cinematic Arts about twenty-four applicants vie for each undergraduate place in production every fall. Most of them want to direct, rather than work in media in any other capacity; and most of them want to work in film, not TV (Banks & Seiter 2007).

So, in our second century of cinema, there exist two opposing forces. At one end is a range of new digital media in the form of YouTube videos, digital storytelling clips or cross-media webisodes across [S] and [M] screens. And in the other direction – an unflinching desire for the feature film at the [L] and [XL] screen scale persists.

[ M ]

At the [M] scale for feature films that are produced with a focus toward DVD distribution, it is the established filmmakers who are exploring ideas of screen scale.

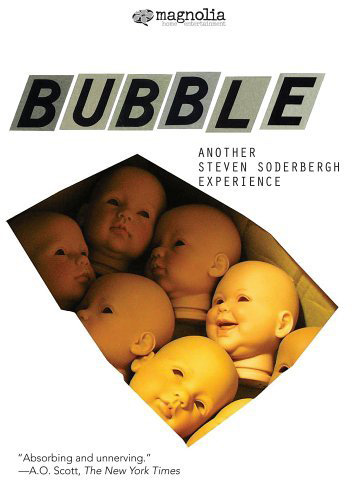

Figure 7: The Bubble ‘experience’

Bubble (2005) is a (relatively) low-budget digital feature from Steven Soderbergh. The film was distributed under a “day-and-date release” model, that is, simultaneous release in movie theatres, satellite, cable television and DVD (Gaspard 2007: 78). This move led some US theatre chains to boycott the film altogether, in protest against the ‘cannibalisation’ of their product. In an interview for Wired Soderbergh predicts: “it will be a while before bigger movies go out in all formats; in five years, everything will” (Jardin 2005). Soderbergh may be right, in light of the recent news from Apple that studio and premier independent features are now available for purchase at iTunes on the same day as their DVD release (2008).

Soderbergh is a cinematic ‘polystylist’ (to borrow a term from David Bordwell) – that is, an eclectic filmmaker who avoids a signature style (2007). Soderbergh expands on the ‘Bubble experience’:

We wanted to do site-specific films. You hear that term used for other art forms, but not for cinema. The writer and I come up with a basic premise, go to a location, and the people fill it up. We interview people, incorporate their stories, try to make it as organic as possible (Soderbergh in Jardin 2005).

The ‘site’ for Bubble is the small town of Parkersburg, Ohio, located in the Midwest of America. The narrative of the film unfolds as a love triangle, murder mystery, which takes place in and around a doll-making factory (one of two remaining in the US) (Gaspard 2007: 79). The film was shot from a script ‘Outline’ (a minimal screenwriting document) and was developed with a local cast of non-professional actors. For Bubble, improvisation was central to Soderbergh’s process. For example, he located his lead actor ‘Debbie’ (Debbie Doeberenier) at the drive-through window of the Parkersburg Kentucky Fried Chicken (Wikipedia 2007).

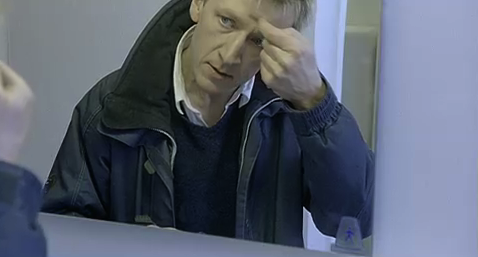

Figure 8 & 9: Debbie Doeberenier as ‘Debbie’ in Bubble:

In terms of narrative scale, Bubble mirrors the small town it depicts. The film fuses documentary stories (of its cast) within a fictional, dramatic framework. Coleman Hough, the screenwriter for Bubble says: “just by observing the life I had landed in the middle of, I fashioned this story. We made some adjustments and that gave us our shooting outline” (Gaspard 2007: 80). In addition, Soderbergh shot and edited Bubble himself, in the vein of DIY digital filmmaking. However, in contrast to the overly familiar DIY digital aesthetic marked by shaky, grainy images cut to abrupt editing patterns - Soderbergh opts for a sophisticated aesthetic, in High Definition (HD) digital video, based on the concept of ‘digital stillness’:

In Full Frontal and K Street, I learned to take advantage of the mobility that digital provides. With Bubble, I wanted to go in the opposite direction and emphasize stillness. Because there isn't film running through the camera, you get an even more pronounced stillness. That's why you don't see much camera movement in the movie, just a lot of cuts (Soderbergh in Jardin 2005).

Figure 10: ‘Digital Stillness’ in Bubble

This can be seen in Soderbergh’s tableau, or ‘postcard’ style compositions in Bubble, often captured with a wide-angle lens. Film critic Roger Ebert notes in his review of the film that Bubble “becomes quietly hypnotic” (2005). Soderbergh also exploits digital colour grading to generate a refined colour palette for the film. On the [M] domestic wide-screen - both these strategies work. Interestingly, Bubble is framed using a wider cinematic ratio, than the 16:9 digital video default, which optimises Bubble to work across the [M] and [L] screen scale. Overall, Bubble is a bold film, one that negotiates screen scale in both narrative and aesthetics via a micro-narrative approach driven by alternative scriptwriting and a refined digital aesthetic for the HD digital video format. But does the film go far enough?

Probably not. However, Soderbergh does reveal his ambition to explore a more radical approach for the feature form, with release of: “multiple versions of the same film…to have a movie out in release and then, just a few weeks later say, Version 2.0, recut, re-scored” (in Jardin 2005). This represents a collision of remix culture and feature film, - an exciting proposition. However, in the domain of low-budget filmmaking – who pays for the alternative versions? Given the recent strike taken by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) over residual payments for new media products, innovative distribution models (like the one suggested by Soderbergh) have an uncertain future. While the studios have their eyes fixed on the new media screens, their hands remain firmly in their hip pockets – a dangerous position with regard to the ‘digital utopianism’ of the next generation of filmmakers:

Digital utopianism threatens decades of union struggles by film/TV practitioners who have fought the endless lines of eager young people (especially those with parents who can support them indefinitely) who are willing to do anything to make it. The WGA radically threatens the cybertarian view of new media that has dominated the discourse of DIY, user-generated content, blogging and all things Web 2.0., by pointing out that all this media production for the Internet is unremunerated—all the videos, photos, and blogs posted on the web (and thereafter the property of the website owners) (Banks/Seiter: 2007).

The feature film is trapped between two poles. At one end, young filmmakers rush to embrace (unremunerated) online distribution for the [S] screen. At the other, more established independent filmmakers, working across the [M] to [L] screen, collide with entrenched industrial practices. While Soderbergh proposes a radical future for the feature form, deployed as ‘recut’ versions to work across the screen scale – it is a model that remains to be implemented.

[ L ]

For the [L] screen, typical to art-house cinemas and film festival screens, enter another polystylist: Lars Von Trier.

Figure 11: Lars Von Trier rides Automavision in The Boss of it All (2006)

In the last decade, Von Trier has been a key player in experimental filmmaking practice. From the raw Dogme aesthetic of The Idiots (1998), to his ‘dark musical’ captured by digital camera rigs in Dancer in the Dark (2000), to the austere, Brechtian-inspired Dogville (2004). His new film, The Boss of It All, is tagged ‘an office comedy’. It screened at the Melbourne Film Festival (2007). Like Bubble, the film is a low-budget production that is shot over five weeks with a small cast and crew. For The Boss of It All, Von Trier introduced a randomised computer controlled system of cinematography called Automavision:

For a long time, my films have been handheld…That has to do with the fact that I am a control freak. With Automavision, the technique was that I would frame the picture first and then push a button on the computer. I was not in control - the computer was…(Von Trier in Macnab 2006).

Automavision generates skewed and off-kilter images and a random mise en scène. Von Trier claims that this system was developed “with the intention of limiting human influence” through “choosing the best possible fixed camera position and then allowing a computer to choose when to tilt, pan or zoom” (in Macnab 2006).

Figure 12 & 13: The Boss of it All shot with Automavision

In terms of screen scale, it is interesting to consider a ‘re-mix’ of these two preceding ideas for the feature form. That is, to meld Soderbergh’s notion of feature film ‘recuts’ together with Von Trier’s Automavision which is executed in a digital environment. This recipe points an automated mode of digital cinema – and the feature film deployed across the screenscape. The potential here is for a mise en scène and film language to be designed (and optimised) for each screen scale: from [S] to [XL]. In this approach, the randomisation of Automavision could be replaced with a more focused computer-controlled cinematography system, one used to generate a ‘database’ of shot sizes, framings and compositions, assembled into alternative recuts in post production. And here, feature film meets new media. This provides a working example of Lev Manovich’s new media principle of “variability”- the idea that a media object can “exist in different, potentially infinite versions” (2001: 36).

[ XL ]

In today’s economy of attention, the battle of screens rages. Advertising for [XL] screens of the multiplex and megaplex is tagged with the footnote: ‘See it Bigger, See it Better, See it First: Only at the Movies’. With regard to the first part of this catchphrase ‘See it Bigger’ - there are signs of scale effects for the [XL] Hollywood blockbuster: in terms of both narrative structure and film language. And this represents a counter attack from the studios against the YouTube insurgency. A survey of scripts from the recent slate of ‘Tent Pole’ films comes in pretty heavy indeed (literally): Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End runs for 168 minutes (approximately 168 pages of formatted script) and Spider Man 3 clocks in at 140 minutes (140 pages). This trend towards narrative elongation can be situated as a drastic response to the precession of YouTube and ‘Clip Culture’, where the average duration of a clip is around 2 ½ minutes (Giest 2007).

The amplification of [XL] feature narrative is also evident in Casino Royale (2006) – but this time - at the level of the cinematic part, not the elongated whole. The duration of the film at 140 minutes is lengthy, but this is historically consistent with the Bond franchise. What Casino Royale does highlight is evidence of an increasingly intensive focus on the scene as a cinematic unit in blockbuster cinema. The film begins with a brief prologue (in monochrome) that introduces the new Bond (Daniel Craig). A dynamic chase sequence follows (which provides the setup for the film) between Bond (Craig) and his antagonist played by Sebastien Foucan (founder of the new ‘free-running’ urban sport). The chase takes place across a building site in Madagascar and lasts for 9-minutes. This scene is hyperkinetic: it exploits ‘run-and-gun’ cinematography and rapid cutting to effect. In Creative Screenwriting one review described the scene as “the foot chase to end all foot chases” (Davis 2007). And for this scene (if not the entire film) Casino Royale operating at the [XL] scale, meets the ‘Bigger.. Better..’ mantra of the studios.

Figure 14: Sebastien Foucan in full flight in Casino Royale

The ‘Bigger Better’ drive, on the [XL] screen, amplifies narrative scale in two ways: 1) an elongation of the feature form and 2) an increased intensity of the cinematic part (or scene). In Casino Royale, the episodic narrative structure is not new - this is typical to the Bond films. Rather it presents as a screen mutation within a given narrative pattern. In this logic the chase sequence (as an anticipated narrative component) is ‘scaled-up’ as a cinematic unit: both its intensity and duration. It works as a kind of ‘super-clip’ inserted within the feature form and is designed to connect with a YouTube fuelled clip culture. As a scale effect or mutation, it works within the framework of Classical Hollywood narrative and supports David Bordwell’s argument against the presence of a ‘Post-Hollywood’ cinema where action movies are deemed to be “loose assemblies of chases, fights, explosions, stunts, and CGI effects, with little narrative coherence” (Bordwell 2007):

Far from rejecting traditional continuity in the name of fragmentation and incoherence, the new style amounts to an intensification of established techniques. Intensified continuity is traditional continuity amped up, raised to a higher pitch of emphasis.” (Bordwell 2006: 121)

Kristin Thompson (on Bordwell’s website) also reminds us of the “flexibility” of the Classical narrative model “that can absorb new technologies and new influences from other media and bend them to its own uses” (2007). Here, the Casino Royale chase scene functions as both a great scene and a great YouTube clip – one that has accrued close to 200,000 views in a matter of months (May 2008).

Figure 15: Casino Royale chase scene on YouTube

Now to return to S,M,L,XL, and Rem Koolhaas promotion of scale as the key quantity of contemporary architecture and urbanism. Koolhaas promotes a theory of “Bigness” to explain the new breed of “hyper architecture”, executed in the form of gigantic malls, IKEAs, airports and casinos - where ‘design’ proceeds through sheer size, and volume, alone (1995: 500). Koolhaas’ “Bigness” is also operating in screen media. In the new ‘design’ of Hollywood blockbuster cinema there are steroidal-scenes (as super-clips) together with an elongated Classical narrative structure. Like buildings, this new form also proceeds “through contamination rather than purity and quantity rather than quality” (1995: 500). However, via Bordwell and Thompson, these screen mutations don’t mount a threat to the dominant Classical narrative system. Also akin to new ‘Big’ architecture, the new Blockbuster feature form is “not the same as fragmentation: the parts remain committed to the whole” (1995: 500).

Mission Impossible III (MI III) (2006) presents another example of screen mutations operating at the [XL] scale. It uses a prologue to introduce special agent Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) and his antagonist Owen Davien (Philip Seymour Hoffman). The film was written and directed by J.J. Abrams, who comes from a background in television production, in series such as Alias and Lost. For MI III, Abrams transports a [M] television aesthetic to the [XL] screen: he uses tight framings when he cuts in Close-Up (CU) between Hunt and Davien. This technique makes for a thrilling start to the film (the best in the franchise by far). Again this scale-effect or mutation is consistent with Bordwell’s notion of “intensified continuity”, where “tighter framings on actors, faster cutting, and prowling camera movements have modified but not replaced the standard continuity approach” (Bordwell in Thomson 2007).

Figure 16 & 17: Mission Impossible III (2006): The Prologue

Across the screenscape from [S] to [XL], this article has highlighted new and innovative approaches to the question of screen scale. The focus has been on the feature form: its narrative scale (patterns, scripts and modes of narration) and the scale of the moving image itself (mise en scène, film language and aesthetics). The phenomenon of FEM has propelled the feature into Web 2.0, viral marketing and the world of social-networking. Here, new narrative models are in their infancy, including Digital Storytelling and cross-media production. However, with these new opportunities an ambition for the feature form, and its theatrical distribution, remains strong for the next generation of filmmakers.

For the [L]-[XL] screen, the cinephiles lament a “downsizing” of cinema in the digital age (Matthews 2007). In contrast, this article reveals that the news is not all bad. Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble is an innovative film that explores a ‘site-specific’ and ‘micro’ approach to feature narrative and works with a refined digital video aesthetic for the High Definition format. He also talks up the idea of ‘recuts’ released as alternative versions of a feature film. Lars Von Trier’s new Automavision system in The Boss of It All foreshadows the potential for narrative database cinema – where the feature could be (re)distributed across the screenscape in multiple scales. At the same time the new Blockbusters, like Casino Royale and Mission Impossible III, highlight some creative responses to competing screen media. At this [XL] scale there are signs of both amplification and an excess of narrative. This has mixed results. At the level of the cinematic part it has worked well: on the [S] screen (a feature fragment as a YouTube ‘clip’) and the [XL] screen as an intense cinematic experience. However, the elongation of the feature form (in the logic of Rem Koolhaas’ theory of ‘Bigness’) sees the Blockbuster pushed to its very limit – and reads as a desperate response to the ongoing precession of clip culture.

This journey across the screenscape does not conclude with any prophecy of doom and gloom. Instead it finds a fertile territory in a digital environment, marked by a hybridity and cross-pollination of screen media. Here, the feature form coexists and interacts with new narrative models, language and aesthetics for the moving image. A range of creative and productive responses to screen scale can be located. Those that excite the most work as screen mutations or scale effects and affirm the feature form as a fluid, dynamic quantity within the screenscape.

References

Apple Inc. Hot News (2008) Purchase New Movies on iTunes Same Day as DVD Release, http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2008/05/01itunes.html?sr=hotnews.rss, accessed May 2, 2008.

Banks, M. & Seiter, E (2007) “Spoilers at the Digital Utopia Party: The WGA and Students Now”, FlowTV, vol. 7 no. 4, http://flowtv.org/?cat=125, accessed December 13, 2007.

Bordwell, D. (2006) The Way Hollywood Tells It, Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bordwell, D. (2007) “Anatomy of the Action Picture”, David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema, http://www.davidbordwell.net/essays/anatomy.php, accessed December 10, 2007.

Bordwell, D. (2007) “Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists”, David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema, http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1139, accessed December 12, 2007.

Cole, L. (2006) FEM, Shooting People, http://shootingpeople.org/shooterfilms/interview.php?int_id=77, accessed December 12, 2007.

Corbett, C. (2007) “Webisodes for Kids”, The Media Report, ABC Radio National, (December 20), transcript at http://www.abc.net.au/rn/mediareport/stories/2007/2124198.htm, accessed December 23, 2007.

Crumley, A. (2007) “Cyber-Born Film Panel”, Destination Film Festival, Saturday 8th December 2007.

Dancyger, K. & Rush, J. (2007) Alternative Scriptwriting: Successfully Breaking the Rules, Oxford: Focal Press.

Davis, J. (2007) “Pretty Sharp for a Blunt Instrument”, Creative Screenwriting, http://www.creativescreenwriting.com/csdaily/dvds/03_16_07_CasinoRoyale.html, accessed December 14, 2007.

Ebert, R. (2006) “Bubble”, rogerebert.com, http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060126/REVIEWS/60117006/1023, accessed December 12, 2007.

Gaspard, J. (2006) Fast, Cheap & Under Control, Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese

Gaspard, J. (2007) Fast, Cheap & Written That Way, Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese

Giest, M. (2007) “The Rise of Clip Culture Online”, BBC News,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4825140.stm, accessed May 23, 2007.

Griffith, E. (2008) “Quarterlife’s NBC Debut Tanks”, AppScout, http://www.appscout.com/2008/02/quarterlifes_nbc_debut_tanks.php, accessed April 30, 2008.

Harper, G. (2005) “DVD and the New Cinema of Complexity” in New Punk Cinema, ed. N. Rombes, Edinburgh University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence Culture, New York/London: New York University Press

Jardin, X. (2005) “Thinking Outside the Box”, Wired, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.12/soderbergh.html, accessed December 12, 2007.

King, G. (2005) American Independent Cinema, London/New York: I.B.Tauris

Koolhaas, R. & Mau, B. (1995) S, M, L, XL, New York: Monacelli Press

Lyons, C. (2005) “Join a Revolution. Make Movies. Go Broke”, The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/20/movies/20lyon.html, accessed December 12, 2007.

Macnab, G. (2006) “I’m a Control Freak but I’m Not in Control”, Interview with Lars von Trier, The Guardian, http://film.guardian.co.uk/interview/interviewpages/0,,1878115,00.html, accessed December 12, 2007.

Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media, Cambridge: The MIT Press

Matthews, P. (2007) “The End of an Era: A Cinephile’s Lament”, Sight & Sound, no. 17 (October)

Murphy, J.J (2007) “A Skeptical View of You-Tube”, J.J. Murphy on Independent Cinema, http://www.jjmurphyfilm.com/blog/index.php?s=four+eyed+monsters, accessed December 11, 2007.

Pierce, J. (2005) “The Fourth Screen”, Off the air: Screenrights Newsletter, http://www.joemiale.com/press/screenrights_01.pdf, accessed November 5, 2007

Pierson, J. (2004) “Slacking Off”, Slacker: The Criterion Collection, http://www.criterion.com/asp/release.asp?id=247&eid=373§ion=essay&page=1, accessed December 11, 2007.

Spencer, M. (2007) “Week 3: Cyber-Born Film”, Destination Film Festival, http://www.destfest.com/week-3-film/, accessed December 10, 2007.

Thompson, K. (2007) “Classical cinema lives! New evidence for old norms”, David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema, http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=412, accessed December 10, 2007.

Van Couvering, A. (2007) “What I Meant to Say”, FilmMaker Magazine, http://www.filmmakermagazine.com/spring2007/features/mumblecore.php, accessed December 11, 2007.

Willis, H. (2005) New Digital Cinema: Reinventing the Moving Image, London: Wallflower Press.