Somatic Technologies: Embodiment, New Technologies and the Undead

Anne Cranny-Francis

After the publication of Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (Haraway 1991) the trope of the cyborg, already widely deployed in science fiction, became a major tool for critical analysis of the relationship between human embodiment and technology. The striking feature of this trope has always been its power to express not only ideas, but also feelings, about technology and being; it is not only an intellectual tool, but also affect-laden. For contemporary western users of information technology it enhances access by providing an imaginary relationship between the user and the interface, which enables users to manipulate the interface effectively. Also, because of its hybridity (the cyborg has always been a composite being – human/human (as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein [1818]), human/animal (as in Wells’s Island of Dr Moreau [1896]), human/machine (as in James Cameron’s Terminator films [1984, 1991]), the cyborg also articulates contemporary perceptions of the nature of embodiment, implicated as it is with digital and bio-technologies. Which raises the question of why the cyborg trope has this power; from where does it derive?

This paper argues that the power – material, cultural and political – of the cyborg figure derives, at least in part, from its semiotic and cultural antecedents, of which one of the most important is the image of the crucified Christ. In making this argument I am not supporting the notion, sometimes identified in Haraway’s writing, that the cyborg – and technological embodiment – is a specifically western phenomenon. Rather it is to note that the success of the trope of the cyborg – in any culture – relates to its textual history, its intertextual references to earlier cultural figures and the meanings and feelings they articulate, and which individuals negotiate in their ongoing generation of embodied being. In western cultures, this intertextual history includes the iconic image of the crucifixion.

Introduction

In the television series, Star Trek: The Next Generation (1988-94)a high-rating double episode, “The Best of Both Worlds” (1990) showedthe Captain of the Starship, Enterprise, Jean Luc Picard forcibly transformed into a Borg – a cyborg member of a collective entity known as the Borg. This ‘cyborging’ of the captain – when he is multiply pierced and implanted with prosthetic devices – mobilised references to the crucifixion of Christ to constitute a text that expressed and resolved contemporary fears about white masculinity (Cranny-Francis 2000).

Fig 1: Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) transformed into Locutus of Borg

The piercing of the captain’s body articulated contemporary concerns about the penetration of the body – and particularly of (homosexual) male bodies – by the AIDS virus; about the challenge to male authority, symbolised by the impenetrable, hard male body, by feminism; and about the threat to the authority and dominance of white masculinity posed by the multiplicity of non-white voices now speaking within western societies. Analysis of the episode showed that the allusions to the crucifixion aligned the power and authority, as well as the erotics, of the crucified Christ with the narrative figure of the authoritative white male (Picard), reinforcing the power of white masculinity and, at the same time, reiterating the semiotic and cultural power of the crucifixion image.

This evocation of the crucified Christ is not simply a localised referent for that particular cyborg image (the Borg), but underlies many contemporary western uses of the trope. And it is this semiotic and cultural history that makes the cyborg such a powerful referent now. Later in the paper I specify how the image of the crucified Christ can itself be read as a cyborg.

My argument is conducted via a series of encounters: a reading of the figure of Christ’s body in late Middle Ages devotional texts, in which the hybridity of Christ is both celebrated and fetishised; the recent appearance of hybrid and cyborg figures in the Stephen Sommers’ film, Van Helsing (2004) and the excess of religious (mostly Christian) references throughout the film; and a mapping of the homologies between the figures of Christ crucified and Sommers’ representation of Dracula, which suggests their interrelationship. This paper is based in a belief in the inextricable relationship between embodiment and the technologies (material, cultural and political) that generate it, the semiotic density of those technologies, and their iterative deployment to generate new ideas – about technology and about embodiment.

The body of Christ

The combination of power and pain – and a body subjected to multiple piercing – constitutes the erotics of the figure of the crucified Christ, and its fetishisation. The veneration of the crucified Christ was a particular feature of late medieval devotion, and can be related to a number of religious, political and social debates. Sarah Beckwith is one of a number of recent scholars (Ash 1990; Beckwith 1993; Bynum 1991/1995; Steinberg 1996) who have written about the significance of Christ’s body, which she describes as “by the late Middle Ages (if it hasn’t always been) a fundamentally unstable image, a site of conflict where the clerical and the lay meet and fight it out, borrowing from each other’s discourses” (Beckwith 1993: 32). Beckwith understands this figure in Bakhtinian terms, by reference to Stallybrass and White’s study of hybrid images for whom the hybridisation creates:

… new combinations and strange instabilities in a given semiotic system. It therefore generates the possibility of shifting the very terms of the system itself … by erasing and interrogating the relations that constitute it. (Beckwith 1993: 63)

So, the hybrid figure of the medieval Christ can be seen as destabilising the assumptions of conventional theology, and as interrogating the terms that structure that theology – including the relative status of sacred and profane within Christian worship, and the hierarchical relationship between the Church (ecclesiastical authority) and the laity.

Christ’s body is hybrid in that it is both sacred and profane, human and divine, God and man. This hybridity gave rise to a range of debates about the relative status and power of the two terms in this formulation: was the profane or the human subject to the sacred and the divine – or alternately, was the sacred and divine dependent for its definition and being on the profane and the human?

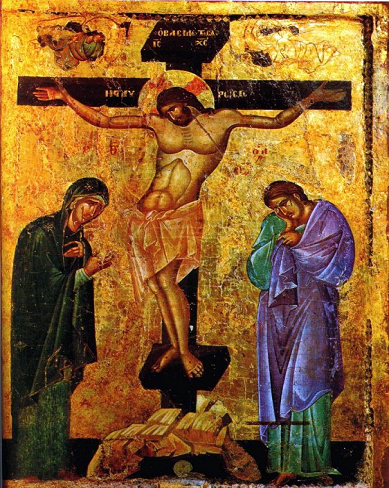

Fig. 2: The Crucifixion, Tempera on wood, 96 x 67 cm, legend in Greek, second half 13th century, Icon Gallery of St. Clemence Church, Ohrid, Macedonia

That debate erupted even more fiercely in the devotion to the crucified Christ, as here the boundaries of Christ’s body are most clear – and most clearly perforated – so that those boundaries are no longer as firm as we might assume. In these devotions, for example, the scourge that bites into Christ’s flesh, the thorns that pierce his brow, the nails through his hands and feet and the spear that enters his side are sacralised – made sacred – by their entry into the sacred flesh of Christ. They, like the wounds themselves, became the focus of intense contemplation and devotion. The wounds too are, in Beckwith’s terms, ‘densely elaborated”. In some devotions, the wound in the side becomes a breast to be sucked; in others it is a “womb in the act of perpetual parturition”. This perpetual birthing enacts the union of Christ’s redeeming tortured body with that of the infant soul around which the wounds stay perpetually open. In this image the boundary between Christ’s body and that of the devotee is lost – as it is in the image of the suckling. (Beckwith 1993: 59)

Mary Douglas has written extensively on this function of the skin as boundary, and the psychic consequences of a loss of skin integrity; for Douglas it interrogates the very notion of identity (Douglas 1966), which is a significant function at a time of theological, political and social struggle. In the late Middle Ages it enabled Christ’s body to function as a site of political struggle; for example, between the laity and the Church, over the roles of each and of the identity of the individual worshipper, as well as between the common people and their leaders – state and ecclesiastical. And this was not just a struggle over ideas; it was a fully engaged and embodied struggle over the nature of being. Beckwith notes of the Christ image at this time:

The affective power and emotive reach of the symbol of Christ’s body lay in the way it could function simultaneously as the most intimate experience and the most public resource; and it was precisely through the connections between these two realms that its political resourcefulness was articulated … (Beckwith 1993: 76)

So Christ’s body is seen as operating in a similar way to that of the contemporary cyborg, articulating concerns about the nature of being in a fully engaged and highly affective manner.

This engagement was facilitated by the devotional empathy with which followers addressed the body of Christ. This was not an object of contemplation, but a subject of identification. The imitatio Christi – the imitation of Christ – became a major form of worship (on the complexities of this devotion, see Steinmair-Pösel on-line), and it was realised most fully in the bodily phenomenon that became widely recognised in the late Middle Ages – the stigmata, the wounds of Christ as they appear on the body of a worshipper.

Fig. 3: St Francis receives the stigmata, Giotto 1300, Louvre, Paris

The first recognised stigmatic (in 1224) was St Francis of Assisi, founder of a religious order whose guiding principles were the imitation of Christ and the recognition of divinity in others (New Advent on-line). Both the Franciscans and the Cistercian monks of St Bernard engaged in a form of worship that sacralised the body, recognising the interpenetration of sacred and profane, and effectively rejecting conservative theology that positioned the human (body) as a debased form of the divine. Their imitatio worship enacted their belief in this interpenetration of sacred and profane, and laid the groundwork for a move away from ecclesiastical authority and the social control of the Church and its feudal representatives – since it argued that, since the divine is in each person, there is no need for an ecclesiastical authority to moderate the relationship between the individual and God.

This debate about the relationships between individual worshipper, the Church and God raged for centuries, with those individuals who challenged ecclesiastical authority often characterised (and even tried) as heretics. It reached its most disruptive potential in the later protestant schisms that resulted in not only fundamental changes to the operation of the Church, but also to the nature of Church/state relations and to the relationship of the individual to the state. So, at the same time we find the imitatio used to challenge relations between individuals and Church, it also articulates the challenge of individuals to the feudal state – summarised in the motto of the Peasants’ Revolt: “When Adam delved, and Eve span/ Who was then a gentleman?”

When the individual enacted the passion of Christ, she or he performed not only an act of religious worship; she or he also laid the groundwork for the modern bourgeois state. That is, the complex and dense discursive, semiotic and iconographic sedimentations of that act of imitation effectively continue to shape and influence contemporary western culture, including its institutions and representations, rather than the more amorphous and ahistorical figure of “being” – and this is strikingly evident in the representations and tropes by which we attempt to understand and explain the embodied experience of new technologies.

Embodiment and technoromanticism

Contemporary technologies and their makers demonstrate striking ambiguity about the meaning and nature of embodiment. My work has mostly explored information and communication technologies where this ambiguity sometimes seems at its most extreme. So we have scientists and cultural theorists exploring the enhancement of the “human” in and by technologies that enhance and diversify human sense perceptions and ways of knowing: for example, by noting the ways in which communication technologies extend human communication over the globe so that humans no longer communicate simply within the radius created physically by their hearing, but have their hearing sense enhanced by technologies that enable them to hear people thousands of kilometres away.

This enhancement by and through technology is part of the on-going definition of the human as technological being. And though we can argue in Heideggerian terms about the role of technology in this understanding of being – and particularly may want to challenge the ways in which technological being can be a pathway to membership of Heidegger’s “standing reserve” (Heidegger 1993: 322) – fodder for the machine, in the sense of The Matrix, we must also note that this understanding of technological being is fully engaged – that the being in the machine is a sensing embodied entity, not an avatar.

Yet some of the same scientists who celebrate the interrelation of technology and human embodiment yearn – somehow nostalgically – for a time when human consciousnesses will be downloaded into computers, where they will live forever! Disembodied and free! The seeming nostalgia in those fantasies betrays their roots in a kind of Romanticism, described by Richard Coyne as “technoromanticism”. Coyne describes romanticism as “the Enlightenment movement that reacted against the rationalism of the day” and he goes on to argue that:

If rationalism explicated the world of objects, certainties, and the reducible, then romanticism disclosed the culture of the subject, human feeling, emotion, and wholeness. (Coyne 1999: 29)

But Coyne also notes that romanticism is “idealistic in that it elevates the existence and importance of ideas over matter, in the manner of philosophical idealism but also in the everyday sense.” (Coyne 1999: 30) So, despite the romantics’ elevation of the “human” spirit or essence or ideal, they shared the general Enlightenment preoccupation with ideals and essences; in Coyne’s terms, they did not “break… from the tenets of the Enlightenment” (Coyne 1999: 29); body and mind or spirit were essentially in conflict. This same vision of embodiment mobilises the “technoromantic” visions of The Matrix (1999) and of cyberpunk fictions since William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1986), where the human body was characterised as “meat”, the “wetware” that enabled the inhabitant or owner – but not the “being” – to move with total freedom through the virtual world of the matrix.

In these visions the individual is not identified with or through her/his body, which is simply a biological support system for the mind. The essence of the person is the free-roaming “mind” or consciousness, though Gibson himself challenges this idealism in Neuromancer by having his main character, Case’s consciousness/mind downloaded into an unfamiliar and differently-sexed body. Case’s shocked responses to his differently embodied experience reminds the character, and the reader, that “meat” matters. The individual bereft of embodiment is no individual at all.

Yet the fantasy persists. I heard scientists on the ABC earlier this year expounding the possibility of downloading human consciousness into a machine – with a fervour and enthusiasm I last heard when one of the administrators at my university talked of replacing academic staff with on-line teaching programs. There is a kind of born-again enthusiasm in these pronouncements that is disturbing – because it is not just a fantasy; it operates as a contemporary somatic technology. That is, it works to fashion the way we experience our bodies, which, for the technoromantics, is as organic support systems of our essential (disembodied) minds/selves.

At the same time, however, a range of texts – both fiction and non-fiction – is challenging this romantic, idealist ontology. Studies such as the recent anthology, Empire of the Senses: the Sensual Culture Reader (2005) explore the contribution of the senses to contemporary understandings of being, through historical and theoretical studies of the embodied, sensory/sensing subject. In a less scholarly, but differently engaging way, the film, Van Helsing (2004) explores the messy embodiment that confronts idealist visions of technological being – and it does so through the sensual engagement that is the subject of contemporary Sense Studies.

Van Helsing

Stephen Sommers’ Van Helsing combines the stories of Victor Frankenstein and his creature with that of Dracula: the former, Frankenstein published at the beginning of the 19th century (in 1818) and of the Industrial Revolution; the latter, Dracula published at the end of the 19th century (in 1897) when the Industrial Revolution had transformed British – and Western – society. The two stories are striking in that they both contain characters that have entered into the cultural history and memory of the West – Frankenstein’s creature and the vampire, Dracula. They also both deal prominently with technology; in Frankenstein the renegade scientist, Victor Frankenstein uses a combination of contemporary technology and older alchemical ideas to create his creature. In Dracula the vampire hunters, led by Van Helsing, use 19th century technology – including the typewriter, the dictaphone, the railway – again combined with older lore (the pointed wooden stake, garlic), along with Christian symbols (the cross, communion host) – to defeat their enemy, Dracula. Sommers’ film deploys many of these ideas and images, with the pivotal point – the point at which the two stories coalesce – being the development of a technology which Dracula jubilantly characterises as “a triumph of science over God”. (And note that Dracula’s statement raises the issue of the relationship between science and technology (the latter being the visual referent for Van Helsing) – a debate cogently addressed in Don Ihde’s Philosophy of Technology (1993)).

God – meaning the Christian God – features throughout Van Helsing, though the scientists gathered in the Vatican basement include members of many different faiths (including Islam and Buddhism). Several times Van Helsing himself is described as “the left hand of God”, significantly by both a Catholic Cardinal and Dracula; the Catholic Church fosters and supports Van Helsing’s work and he is accompanied through the film by a Catholic friar named Carl; Dracula is described as the son of Satan, and his vampire/undead state is said to be the result of “a pact with the devil”; Dracula (along with his offspring) is depicted as morphing into a Gothic gargoyle or fallen angel (i.e. devil); and Dracula is frequently identified with the image of the dragon, which is traditionally read as a sign of Satan.

From its earliest scenes – in which Frankenstein vivifies his creature in the presence of his technological patron (venture capitalist), Dracula – this film argues the imbrication of religion, technology and the experience of embodiment. Dracula’s attempt to use technology to vivify the (un)dead offspring of his matings with the brides is represented as problematic not because it offends against nature or the moral order, but because of Dracula’s religious experience and significance; his pact with the Devil. So Van Helsing records the impact of the West’s Christian history on its understandings of embodiment, while also situating these concerns in the context of a contemporary technological order. Christianity, technology and embodied being form the problematics of this film, as they did of Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein.

‘The word made flesh’: the creature and the vampire

In Van Helsing we are confronted with multiple experiences of embodiment, which are teased out for their abject and/or erotic potential. As well as Dracula, Frankenstein and Frankenstein’s creature, the film deploys other characters from western Gothic literature and film, including the Wolfman, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (briefly), the vampire’s brides, the vampire children, Dr Frankenstein’s assistant, Igor (not found in Mary Shelley’s original novel but a character in many films of Dracula), the ghoulish grave-digger and the peasant mob.

The movie opens with the construction of the creature by Victor Frankenstein – a fleshly monstrosity, not ‘one man but several’, as Van Helsing later quips.

Fig 4: Dracula (Richard Roxburgh) observes the newly vivified creature (Shuler Hensley) from Stephen Sommers’ Van Helsing (2004)

The creature’s birth or vivification is welcomed by not only his creator, Frankenstein but also Dracula who has funded Frankenstein’s research. In the very moment of Frankenstein’s monstrous embodiment – “It’s alive! It’s alive!” – the audience is shown the “monstrosity” of Dracula’s embodiment, when Dracula turns on Frankenstein. As Frankenstein tries to defend himself with a sword, Dracula impales himself on it, explaining (to the accompaniment of visceral squelching sounds): “You can’t kill me, Victor, I’m already dead.” Dracula, we discover, has his own plan for the creature.

So in Van Helsing the characters who are most closely associated with material technology – in the form of complex machinery – are Frankenstein’s creature and the vampire, Dracula (and his brides and offspring). All are hybrids – the creature, a being made up out of disparate body parts; the vampires, both dead and alive, animate yet without heartbeats.

The creature, of course, is associated culturally and historically with the figure of the cyborg; Frankenstein is considered the first science fiction novel, and the creature the first example of a new fictional trope, the cyborg – a technologically produced being. Which is not to say that there are no predecessors to this figure: fictional constructions of mechanical beings or inanimate constructions who come to life (the doll of Dr Coppelius, the Pygmalion statue, the Golem) have appeared before this. However, Frankenstein’s creature is the first being who is directly animated by a contemporary material technology, rather than divine intervention or alchemy. The creature is the embodiment produced by the Industrial Revolution – an identification deployed by Elizabeth Gaskell in her novel, Mary Barton (on-line; first published 1848) when she describes the rebellious working class as the Frankenstein “monster”:

The actions of the uneducated seem to me typified in those of Frankenstein, that monster of many human qualities, ungifted with a soul, a knowledge of the difference between good and evil.

The people rise up to life; they irritate us, they terrify us, and we become their enemies. Then, in the sorrowful moment of our triumphant power, their eyes gaze on us with a mute reproach. Why have we made them what they are; a powerful monster, yet without the inner means for peace and happiness?” (The Literature Network)

The vampire, on the other hand, is not often read as a trope of material technology – and here Sommers’ film intervenes in the cultural history of this character. As noted earlier, Sommers aligns the vampire with technology whereas Stoker’s novel uses contemporary technology to defeat him (Cranny-Francis 1988). Another major change is that Dracula reproduces sexually, though his offspring are inanimate or undead. Dracula intends to use Frankenstein’s technology to vivify his offspring – as it has already vivified the creature. So Sommers’ film constitutes the vampire as not only hybrid but, like Frankenstein’s creation, cyborg – a creature whose embodiment is inextricably linked with the technology of his time. In Van Helsing it is Dracula, not the vampire hunter, who is the technological entrepreneur.

As noted earlier, this film engages multiply with these hybrid and cyborg embodiments. The creature is an abject figure, as he was for the inhabitants of Shelley’s novel. Monstrous, decaying, a patchwork of disparate flesh; he is technological being at its most abject. Dracula, on the other hand, may bewail his hybrid form – he notes mournfully at one point that “I feel nothing … and I will live forever” – but he follows this with a defiant laugh. Dracula revels in his difference, his hybrid, cyborg embodiment, declaiming: “I am at war with the world and everyone in it.” In fact, this characterisation is very like that of Lucifer in Milton’s Paradise Lost who declares: “Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.” (Book 1, line 264) (Milton 1968: 477) This pain, this sense of dislocation, is crucial to the characterisation of Dracula – and appears in the most famous film versions of the story. In Todd Browning’s Dracula of 1931, for example, Dracula muses at one point: “To die, to be really dead; that must be glorious. There are far worse things awaiting man, than death.” Gary Oldman’s Dracula in the Coppola film from 1992 is also a romantically mournful figure, whose genesis and salvation are at the hands of his beloved Elizabeth (born again for him in the person of Mina Harker). Dracula is both intensely emotional, and unable to feel; at war with the world and yet defiant to the end. He is a character of excess – whether of pain or pleasure.

The power of this character – his defiance in difference – renders him an intensely erotic figure, as he has always been for Stoker’s readers, despite the abject elements with which Stoker attempted to qualify the character (Stoker described Dracula as having rancid bad breath, and hair growing on the palms of his hands). Dracula’s embodiment is not abject, like that of Frankenstein’s creature, but highly sexualised. This is evident in all of the film versions of the Dracula story. In Van Helsing it is most clearly seen in the ‘masked ball’ scene in which Dracula dances with the vampire hunter, Anna Valerious whom he has captured.

Fig 5: Dracula (Richard Roxburgh) dancing with captive vampire hunter, Anna Valerious (Kate Beckinsale)

He taunts her with his desire to make her into one of his brides, holding her close, biting her when he kisses her, holding her hands against his chest and laughing when she feels no heartbeat, dancing with her before a mirror to show that he has no reflection (though his body is all the more palpable for its invisibility, as it invites the viewer to supply the absence). The scene is a sensual feast – beautiful and strange music; the rich, gold costumes of a Venetian masked ball; acrobatic performers creating a decadent mise-en-scene; the ornate architecture of the palace in which it is staged; a sensuous swirl of light, sound and movement – in the midst of which is the vampire and his beautiful captive who move together through the steps of a ritual dance.

Although Bram Stoker’s original characterisation of Dracula stressed the abjection of his embodiment, readers have consistently engaged with its eroticism. That eroticism is articulated in the excess of affect that is associated with this displaced Eastern aristocrat, beside whom his bourgeois hunters have always appeared colourless and rather inadequate. But it also derives, at least in part, from his pain – the fact that he is constantly “at war with the world”. He is “other” – hunted, constantly under threat of death from a piercing stake, though in Sommers’ Van Helsing Dracula seems immune to impalement. He both impales himself (as noted of the opening scene) and later simply withdraws the stake with which Van Helsing attempts to destroy him. In fact, Sommers’ Dracula mobilises the sexual fetishism of the phallic stake; like Picard of Star Trek: The Next Generation he is multiply, excessively pierced – and, consequently, extraordinarily and ecstatically powerful.

Somatic technology

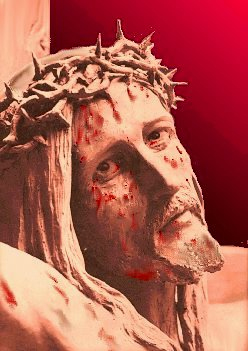

The body of Christ that is worshipped in the imitatio is not the healthy, living Christ, but the tortured, brutalised and crucified Christ. This is the body of the Five Wounds (Bynum 1991: 271) – the body that is cut and pierced; the body of Christ nailed to a cross in a monstrous act of prosthesis. This prosthetic attachment of the tortured body to the wooden artefact of the cross constituted a cyborg generated by the material and political technology of that time – and subsequently reproduced and psychically reactivated in Christian societies.

Fig. 6: The hours of the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ by Luisa Piccarreta , little daughter of the Divine Will

As a hybrid figure the body of Christ challenged hierarchical readings of the relationship between sacred and profane. As a cyborg Christ’s body was infinitely more evocative; its violated and broken boundaries destabilised boundaries between sacred and profane (as did the hybrid) but also invited the worshipper into the body itself. The crucified body was both a locus of desire (Christ the lover, a fetishised object of contemplation) and a focus for imitation (a being-with the tortured body of Christ that engages the worshipper bodily in the act of contemplation and devotion). The worshipper wanted (and wanted to be) Christ crucified.

As noted above, the Bakhtinian reading of the hybrid shows how it disrupts established semiotic practice, and facilitates the development of new ideas by interrogating the assumptions of the system in which it is generated – as the hybrid Christ in the late Middle Ages interrogated ecclesiastical authority. The cyborg figure has the potential to function even more radically. The cyborg articulates the already fundamentally technological nature of being; that human subjects are never without or outside of technology, but are formed in and through their technologies, which are material and political and social and cultural (including religious). The cut and perforated crucified Christ, the Christ/cross cyborg that constitutes the crucifixion, articulates both the material and political technologies of Christ’s own time, and the cultural, religious and political technologies of the late Middle Ages and their subjection of the individual to the power of Church and state. And it also makes visible the mechanisms of those technologies, including the psychic mechanisms (eroticism, desire, fear) by which they engaged medieval worshippers, constituting them as embodied subjects.

The formative interaction of these technologies with human embodiment constitutes a set of somatic techniques by and through which individual subjectivities are constituted. These techniques embody the individual subject via a range of cultural narratives and tropes in which both the technologies and the individual subjects are embedded – and through which they are produced. These are the semiotic practices – the stories, characters, tropes – through which individuals and societies understand themselves and their world. They are also the means by which technologies (material, social, cultural, political) are accessible to and incorporated into the lives of individuals – and include the redemptive narrative of Christianity and the progress narrative of bourgeois society, as well as the figures of hero, villain and others that populate these narratives.

They also include the figure of the cyborg, which is so popular in contemporary writing about technology. As currently conceived, this cyborg figure is a visible realisation of the prosthetic enhancement of human embodiment. But as this paper argues, it is even more powerful as an articulation of the already technological nature of human embodiment, which may or may not be physically apparent or visible. And the figure is semiotically and culturally powerful and effective because it is not a new idea or concept but is deeply embedded in western consciousness and subject formation through its earlier manifestations in Christian devotion, which was erotically-charged, affect-laden and corporeally manifest.

Stephen Sommers’ Van Helsing shifts the focus of the story about technology and embodiment from Frankenstein and his creature to Dracula, so that the vampire (like the medieval Christ) is not only hybrid but also cyborg. So the already-erotic characterisation of the vampire resonates with the excessive (and eroticised) image of the crucified Christ to generate a powerful figure of fear and desire for contemporary social subjects. Reading the vampire as cyborg in relation to its earlier manifestation in the figure of Christ’s body enables us to locate the psychic mechanisms by which it operates, and which explain why the image is so effective and powerful.

When Sommers mobilised his reading of the vampire as a technological being, a cyborg, he evoked a somatic technology deeply embedded within western consciousness through the religious discourses that suffuse western understandings of embodiment and being – even in those for whom religious practice is no longer a conscious activity. As noted above, the image of the crucifixion is simultaneously abject and erotic, and the source of this apparent contradiction is the power of the embodied figure, who could refuse this sensory torture, but does not.

Dracula, too, has always combined abjection and desire – a contradiction motivated and enabled by the (aristocratic) power that informs his being. Dracula always did outclass (literally and figuratively) his bourgeois pursuers. Sommers evokes not only Dracula’s aristocratic history (title, castle, feudal servants); he also activates the Satanic associations of Dracula (Dracul, the dragon, icon of Satan) who revels in the overwhelming tragedy of his Fall. Dracula, like Satan, is broken but radiant with power – like the crucified Christ.

Contemporary cyborgs frequently enact this Christ-like combination of ab/sub/jection and eroticism – Roy Batty and his self-imposed stigmata, the Terminator who pierces his own flesh repeatedly to save the innocent, Neo whose being interrogates the messianic predictions of technophiles, and Sommers’ Dracula whose undead flesh is the source of both power and pain and for whom technology offers no solution to his accursed “otherness”. These characters are sensually powerful, intensely erotic, not because they elude or deny embodiment – in the tradition of western asceticism, but because they embrace their tortured being – as Christ accepts his suffering for humanity. Their sensual power derives not simply from their similarity to the image of Christ, but from their genealogical evocation of a (Christian) somatic technology through which we all negotiate our own subjectivity – and the complex sensuality that characterises western embodiment.

References

Ash, J. (1990) "The Discursive Construction of Christ's Body in the Later Middle Ages: Resistance and Autonomy" in Feminine/Masculine and Representation, ed. T. Threadgold and A. Cranny-Francis, Sydney: Allen & Unwin

Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays, trans. C. Emerson & M. Holquist, ed. M. Holquist, Austin: University of Texas Press

Bakhtin, M.M. (1984) Problems of Dostoyevsky's Poetics, ed. & trans. C. Emerson, Manchester: Manchester University Press

Bakhtin, M.M. (1986) Speech Genres & Other Late Essays, trans. V. McGee, ed. C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Austin: University of Texas Press

Beckwith, S. (1993) Christ’s Body. Identity, Culture and Society in Late Medieval Writings, London: Routledge

Bernardi, D. (1997) "Star Trek in the 1960s: Liberal-Humanism and the Production of Race", in Science-Fiction Studies, vol. 24 part 2 pp. 209-225

Bynum, C.W. (1991) Fragmentation and Resurrection. Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion, New York: Zone Books

Bynum, C.W. (1995) The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336, New York: Columbia University Press

Coyne, R.(1999) Technoromanticism. Digital Narrative, Holism, and the Romance of the Real, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

Cranny-Francis, A. (1988) “Sexual Politics and Political Repression in Bram Stoker's Dracula" in Nineteenth-Century Suspense: from Poe to Conan Doyle, ed. C.S. Bloom, London: Macmillan

Cranny-Francis, A. (1995) The Body in the Text, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press

Cranny-Francis, A. (2000) “The erotics of the (cy)Borg: authority and gender in the sociocultural imaginary" in Future Females, the Next Generation: New Voices and Velocities in Feminist Science Fiction, ed. M. Barr, Totowa, N.J: Rowman and Allenheld

Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger. An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

Fuchs, C. J. (1995) "'Death is Irrelevant': Cyborgs, Reproduction, and the Future of Male Hysteria" in The Cyborg Handbook, ed C. H. Gray, New York: Routledge

Gaskell, E. Mary Barton, The Literature Network, http://www.online-literature.com/elizabeth_gaskell/mary_barton/16/, accessed November 20, 2006

Gibson, W. (1986) Neuromancer, London: Grafton

Gray, C. H. & Mentor, S. (1995) "The Cyborg Body Politic and the New World Order" in Prosthetic Territories. Politics and Hypertechnologies, ed. G. Brahm Jr. & M. Driscoll, Boulder: Westview Press

Haraway, D. (1997) Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™, New York/London: Routledge

Haraway, D. (1991) Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. The Reinvention of nature, New York: Routledge

Heidegger, M. (1993) Basic Writings. From Being and Time (1927) to The Task of Thinking (1964), ed. D.F. Krell, London/New York: Routledge

Howes, D. (2005) Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader, Oxford: Berg

Ihde, D. (1993) Philosophy of Technology. An Introduction, New York: Paragon House

Milton, J. (1968) The Poems of John Milton, ed. J. Carey and A. Fowler, London: Longman

New Advent “Mystical Stigmata” in New Advent. Catholic Encyclopedia, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14294b.htm, accessed on November 18, 2006

Shelley, M. (1982) Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, ed. M. Hindle, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Springer, C. (1996) Electronic Eros: Bodies and Desire in the Postindustrial Age, Austin: University of Texas Press

Steinberg, L. (1996) The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, 2nd ed., Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press

Steinmair-Pösel, P. “Imitatio Christi and the Concept of Grace”, http://www.cla.purdue.edu/academic/engl/conferences/covar/Program/posel.pdf, accessed November 18, 2006

Wells, H. G. (n.d.) The Island of Doctor Moreau, London: The Readers Library Publishing Co.

Images

Figure 1: http://www.bbc.co.uk/cult/st/gallery/tng1/tnglocutus03.shtml, accessed November 18, 2006

Figure 2: http://www.iconsexplained.com/iec/00040_crucifixion.htm, accessed 18 November, 2006

Figure 3: http://www.giotto.com/giotto/img/0501.jpg, accessed November 18, 2006

Figure 4: http://movies.yahoo.com/movie/contributor/1800287463/photo/509840, accessed 18 November, 2006

Figure 5: http://www.livejournal.com/users/dm1985_photos/, accessed March 27, 2005

Figure 6: http://www.theworkofgod.org/Devotns/Stations/meditations_passion_Christ.htm, accessed November 18, 2006

Filmography

Browning, Todd (dir.) (1931) Dracula, Universal

Cameron, James (dir.) (1984) The Terminator, Orion/Hemdale/ Pacific Western

Cameron, James (dir.) (1991) Terminator 2. Judgment Day, Pacific Western

Coppola, Francis Ford (1992) Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Columbia

Sommers, Stephen (dir.) (2004) Van Helsing, Universal

Star Trek: the Next Generation (1988-94) Paramount Pictures Corporation

Wachoski, Larry & Andy (dir) (1999) The Matrix, Village Roadshow/Silver