Re-telling History in the Digital Age: The Scripting Of Hunt Angels

Alec Morgan

Rupert stands and delivers with rising passion.

|

(Morgan 2006, Hunt Angels, Screenplay Excerpt)

Sydney filmmaker, Rupert Kathner, delivered that message in a courtroom shortly after he was arrested on fraud charges in late 1947. He and his partner, Alma Brooks, had been trying to raise finances, often by illegal means, to make a film about the bushranger, Ned Kelly. Over a span of fifteen years, starting in the mid 1930s, they took on the Hollywood monopolies that dominated the exhibition of films in Australia, a corrupt police commissioner and the cultural cringe in their passionate attempt to make Australian films. They are the subjects of a feature length, non-fiction film, Hunt Angels (2006) which I researched, wrote and directed.

In this article I would like to trace and examine the developmental process of the research and scripting of the film. In particular, the scripting of a non-fiction work during a period of accelerated development of new creative tools and aesthetic choices being offered to filmmakers through the advances in digital technologies and programs. Why is it that given the increasing economic accessibility of these exciting new programs to lower-budget productions, public and commercial broadcasters still insist on the delivery of programs ruled by conventional prescribed templates? In the specific context of the scripting and pre-visualising processes involved in the making of a history-based film, I will investigate how these digital breakthroughs can re-invigorate the telling of the past.

Based on a true story, Hunt Angels uses innovative digital composite techniques to create a synthesis of actors filmed today in a studio and archival photographs and footage taken nearly seventy years ago. The use of a hybrid, of cinematic styles and digital innovations, was not my first choice as a way of telling this story on the screen. It evolved over a period of three years and was brought about by a number of considerations ranging from the desire to utilise different storytelling techniques, the economic realities of low-budget filmmaking, through to the discovery of absences in our popular visual memory.

Discovering Missing Mavericks of the Past

I had never heard of Kathner and Brooks when I first viewed one of their productions in 1998. I was researching and scripting an episode for a television history series on famous Australian crimes and viewed a short documentary called The Pyjama Girl Murder Case (Kathner 1939). I was immediately struck by its graphic telling of a real crime, the brutal murder of an unidentified young woman in 1934. During the twenty years that I have been researching Australian archival film, I had never viewed a non-fiction film that dealt with a true-life murder that had been made in this country as early as this one.

Quite soon after, I discovered inside the vaults of the National Film and Sound Archives, eight editions of a newsreel series made by Kathner and Brooks called Australia Today (1938-1940). Some of the items addressed contentious social issues of the times: inner city slum housing, poverty, unemployment, cocaine smuggling, illegal gambling, nazi spy rings, alcoholism and juvenile delinquency. Although it was obvious that the series had been made with little budget, the content of these newsreels struck me as possibly being the first cine-news items made in Australia that dealt with social problems.

Find the Pieces of the Story

I began a long research process of piecing together the story of Kathner and Brooks from fragments of memories of people who once knew them, scraps of information gleaned from newspapers and trade magazines and the viewing of their films, most of which have somewhat miraculously survived and are now held in the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra. The story that emerged of their dubious moviemaking ventures was compelling, witty and dramatic. I learned that they had defied a warning from the New South Wales Police commissioner, William Mackay, not to make The Pyjama Girl Murder Case. They had soon after broken into the Medical Faculty at Sydney University in an attempt to film the victim’s body. Their independent newsreel series Australia Today had been well received by local audiences But, according to a contemporary of Kathner, Bren Brown, it had been forced out of the few cinemas that dared screen it by the two large newsreel monopolies of the day, the Hollywood-owned, Fox-Movietone News, and the locally-owned Cinesound Review (Brown 2002).

Despite these obstacles, they continued making movies, sometimes by blatantly illegal means. While on the run from the Sydney underworld and the law, they filmed their last feature film The Glenrowan Affair (1951). During their partnership, which ended suddenly with Kathner’s unexpected death in 1954, they managed to produce nineteen film items. Although nearly all of the films made it into cinemas, a remarkable feat for the times, none ever made money.

I wrote the first draft of Hunt Angels as a conventional drama. It was full of scenes about ruthless Hollywood agents in Sydney forcing cinema owners out of business, a corrupt police commissioner who lunched at a nightclub owned by a convicted sly-grog dealer during the crime epidemic that plagued Sydney. It had Rupert and Alma trying to raise finances from wealthy patrons (who were called ‘angels’ in those days, hence the title), and scenes about their filmmaking scams in the desert outback and rural Victoria.

When I sent the script to my readers, the project hit a wall. The fact is, none of them believed the story was true. They all commented that I was imitating Hollywood movies like Bonnie and Clyde (Penn 1967), L.A. Confidential (Hanson 1997) or Ed Wood (Burton 1994) or the Film Noir’s of the late 1940s. These American historical narratives were more familiar in the reader’s memories than our own cultural past.

I was faced with the sobering realisation that I would need to provide a lot of documentary exposition in the script in order for Australian audiences to understand the historical context in which Kathner and Brooks’ adventures took place. That amount of ‘back-story’ could easily kill the flow of the dramatic narrative and make the film very wordy.

There was another problem that confronted me after completing the draft. One that I had been refusing to face: the production cost of reproducing the world of the darker noir side of Sydney, that Kathner and Brooks operated in over a thirteen year period, was going to be very expensive. I had no confidence that I would be able to raise such a budget on a script about two unknown Australian filmmakers. I also wanted to keep the production budget down to a level by which I could maintain creative control over the content and style and not be too pressured by commercial imperatives.

Prescribed Template or Creative Innovations?

My other alternative was to make the film as a television documentary. That would not have been difficult given the amount of interesting research material I had gathered, and my twenty years experience as a practicing documentary filmmaker. Unfortunately, public and commercial broadcasters in Australia increasingly expect documentaries made by independent producers to conform to a prescribed template that their commissioning editors insist is the only format their viewers will watch. This design consists of the ‘tease’ or ‘hook’ edited into the first minute or so of the film that gives viewers a quick over-view of what the film is about. It’s a well-used device that aims to keep viewers from switching to other channels at the start of the program. Other design elements in this template include the set-up, three-act progression and, hopefully, a satisfying resolution. The design of the documentary must also take into account the commercial imperatives of the advertisement break. According to media writer, Natasha Gadd, this is creating a kind of program conformity. She observes that as it becomes increasingly difficult to finance independent documentaries without the television pre-sale, the diversity of documentary styles and content is becoming increasingly compromised.

The Australian documentary has always been recognised as a valuable cultural artefact; however, with the majority of funds from the government coffers assigned to those with a television pre-sale agreement, Australian docos are becoming increasingly homogenised, neatly packaged television programs designed around schedules, slots and audience demographics. (Gadd 2006)

I was not convinced that the constricting structures of the conventional documentary would serve the exhilarating, hyper-real story of Kathner and Brooks. The characters seemed too large, too lively, to squeeze into the straight-jacketed prescribed documentary template. Besides, I wanted to reach a broader audience than those who normally watch historical documentaries on television and, in order to achieve that, I needed to find a fresh approach to the telling. For quite some time, I was stumped as to how to make the story work on film and the script went into the darkness of the desk drawer.

During the process of research and thinking about a possible way of making the film, a small wave of feature-length films and documentaries that pushed the boundaries of cinematic storytelling by the use of advanced digital technologies and techniques, such as computer compositing, matting and animation, were released into the cinemas. The viewing of some of these productions, particularly those that were either low-budget or documentary-based, inspired me to, at least, begin to think of the possibility of using computer digital programs in the making of Hunt Angels.

The Kid Stays in the Picture (Morgen and Burstein 2002) boldly broke documentary conventions by utilising 2-D technologies on a desktop computer to animate still photographs and archival film throughout its entire 93 minutes. There are no ‘talking heads’, only the singular point of view of the film’s protagonist, the legendary Paramount producer, Robert Evans, delivered in Voice Over.

The Academy-Award winning documentary, Bowling for Columbine (Moore 2002) effectively used computer-generated animation designed by the comic book artist, Ryan Sias, in a sequence that tells the early history of the settlement of America. This humorous sequence was positioned inside a conventionally structured documentary investigating the root causes of the countries predilection for gun violence. To me, it was a surprisingly effective and refreshing way of engaging with audiences who would not normally have an interest in that past, or who had perceived it as ‘boring’.

Waking Life (Linklater 2001), a fictional narrative, used a computer software called ‘Rotoshop’, developed by the animator, Bob Sabiston, that creates a complex and multilayered, colourised animation effect out of live footage with actors shot on actual locations.

The software works on the basis of ‘interpolated rotoscoping’: live-action footage is converted to digital files and then ‘drawn over’ using software, echoing the earlier cel-animation rotoscoping seen in the works by the Fleischers and Disney in the 1930s. (Ward 2005: 42)

An Online Solution

It was an exciting challenge to consider the use of new technologies, increasingly available to the medium of filmmaking, to break down the barriers between the subject matter and viewers. The first solution to my problem of how to make the film came swiftly around this time, via a computer program: the online Internet. The New South Wales State Library had recently digitised nearly 340,000 historical still images onto their website, Picman. Trawling through the collection, I discovered a Sydney of the 1930s and 40s that I had never seen before: starkly lit black and white photographs of shop window displays, dark alleys and side-streets, department stores, nightclubs, cheap hotels and gaudy cinema floats, all taken at night. Here was the world that I imagined Kathner and Brooks lived and operated in.

Many of these images had been taken by commercial photographers who had been commissioned by corporations and government departments to provide visual records for company reports and archival purposes. The photos were never intended for public viewing and, to this day, most have not been published. It was like discovering a ‘lost world’ of Sydney’s past, a vividly portrayed visual record of a city that has since vanished from our popular memory.

Looking at these images on the computer, I began to imagine Kathner and Brooks walking down the streets carrying their film equipment, passing by the neon light of a window display for a new Hollywood movie. Their shady world and these night-lit images seemed to synchronise perfectly. These photos, now open to public access and usage, could provide a visual historical context and add a sense of authenticity to their story. Why not then, go one step further and place these two ‘lost’ characters back into these ‘lost’ pictures? Suddenly, I believed I had solved the problem of how to actually make Hunt Angels. And the method of achieving this would be through the use of digital effects technology.

Digital Possibilities

By using advanced digital compositing programs on a computer, it is now possible to create scenes that could have our protagonists, played by actors today, placed into the streets of the 1930s. Creating this image starts with a subject that has been filmed in front of an evenly lit, bright, pure blue background called a Blue Screen. The composite process on the computer replaces all the blue in the picture with another image. In this case, the background plates would be constructed from the historical photographs found on the Internet website. Thus, creating a ‘virtual city’ that the dramatic live action could take place in. Given that the original archival photos are on 35mm negative, it is possible to project them onto a full-sized cinema screen without losing definition.

It was an exciting idea, but first I needed to find out if it was economically feasible. After all, it was not so long ago that the use of visual effects, mattes and blue screen had once been the exclusive domain of Hollywood special effects artists due to their high production costs. I set about designing a small number of storyboards using photocopies of the street scenes found on the Picman Website and took them to experienced digital designers. Their responses were very positive. With the rapid development of financially accessible digital effects programs for use on the desktop computer, the costs of producing the type of composites that I had envisaged have lowered considerably over the past few years. It is now possible to purchase, over the counter, the programs that were used to create some of the effects for high budget features like ‘Lord Of The Rings’ and ‘Batman Begins’.

We also have in Australia an increasing number of talented digital designers emerging from the film schools. Many of them are making their living working on big budget commercials and the occasional Hollywood blockbuster being made at the large studios. These designers were excited by the idea of being able to contribute to the realisation of one of our forgotten stories. Encouraged by this, I spent the next six months gathering images from the Internet site. With these and other materials gathered over the five years of research, I began to script a digital composite version of Hunt Angels.

The final script had 265 special effects shots. Once a daunting prospect, both creatively and financially, all of these effects were able to be achieved by a very small design team led by Melbourne compositor, Rose Draper, using inexpensive desktop systems and operating within a very modest budget. In fact, the number of special effect shots expanded in the edit room to a total of 281. The only major change we had to make to the original composite design concept was in the area of blue screen matting: we substituted the colour blue with green because of the predominant use of blue in 1930s and 1940s clothing.

Writing The Digital Script

During the scripting, I had hundreds of photocopies of archival still images from the Picman website on the desk beside me. At times, I would make simple storyboards of some of the more complicated sequences and use these in my consultations with digital designers about their technical feasibility.

After the script was finished, these storyboards were used as a pre-visualisation aide for investors in order for them to comprehend more fully what we were aiming to achieve on the screen. However, because film investors are not as interested in digital innovations as they are in the storyline, it was important not to labour their reading of the script with technical details. The solution was to add a brief written explanation of the technological process on a separate page before the start of the script. In the script itself, I used brief headings at the opening of each scene such as: STILLS - (Digital Insert) (B&W 1935)

Below, are sections from the script that were later realised by the use of green screen and digital composite techniques:

Shooting Script: the Opening Sequence

The start of the film offered an opportunity to introduce audiences to the main protagonist, Rupert Kathner, and the imaginative and grandiose vision he held for his movies and set them against the city of Sydney of the mid 1930s. The words used in Kathner’s narration were taken directly from his book, Let’s Make A Movie (1945), a somewhat scathing examination of the state of the Australian film industry.

I keeping with Kathner’s sense of whimsy, and as a kind of homage to low-budget filmmaking, I wanted to expose the means by which the sequence was made: celebrate its artifice, rather than hide it. This was achieved by recreating the city at night by using the archival photographs in such a way that they accentuated the use of the desktop digital technology used in the visual composition. Thereby, setting up the style of the film by consciously exposing the audience to what the digital artist, Russell Richards, defines as “the digital aesthetics of production” (Richards 2004):

Digital aesthetics should actively acknowledge the sophistication of both the resulting product and the dynamic nature of production process…from this perspective, hardware, software and content are all-important factors in defining the aesthetic qualities of the digital. (2004: 145)

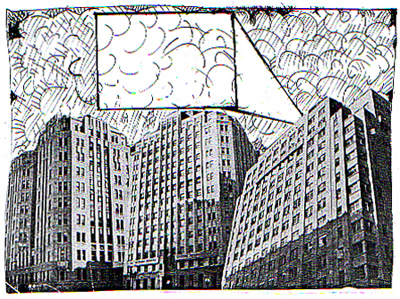

Clips from Kathner and Brooks’ actual films would be digitally inserted into a cloudscape that moved across the city and around the world. This methodology helped create a visual landscape that, to me, expressed Kathner’s ‘world’. A world that belongs more to a dream than to the harsh reality of the era he lived in. Below, is an excerpt from the resulting sequence as it appeared in the script.

FADE IN EXT. SKY OVER CITY. NIGHT. (1935) (Digital Inserts) The blue void sparkles with stars. From the horizon, clouds swarm up and form into a pristine blanket. We hear the VOICE of an enthusiastic young man. This is RUPERT KATHNER.

The rooftop of a high building. A large old-style film projector points upwards. It sparks on and shoots a beam of bright light onto the clouds.

MONTAGE - MOVIES ON THE CLOUDS (Digital Insert) Across this massive natural screen, a young woman wearing a ragged period dress and bonnet rides her horse like lightning, pursued by a mounted trooper.

Drug smugglers flee from customs officers down a dark ally. A bi-plane crashes in the desert. A spy furiously fights with a brave young man. An actor in an over-sized costume shoots a cinematographer operating a hand-cranked camera. The frustrated director throws up his hands. The curled body of a young woman, her head covered with a folded towel, rises to the surface of the clouds.

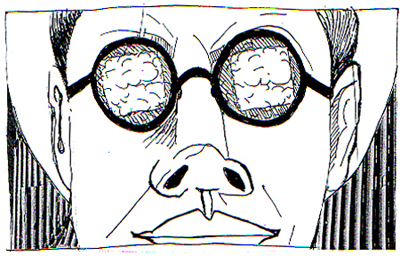

Below, a young man stares proudly upwards. This is RUPE. He wears a 1930s-style dark brown suit, glasses and a felt hat, pulled down.

|

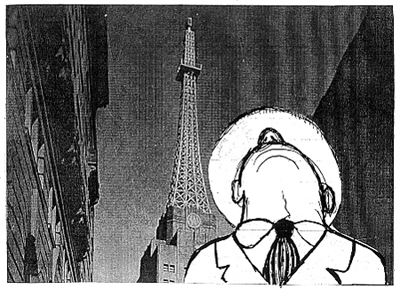

The final film closely follows the narrative of the script. The actor who played Rupert Kathner (Ben Mendelsohn) was filmed inside a small studio against a Green Screen background and later digitally added to a composite background made up of the archival photographs and footage.

Great banks of white clouds fill the sky... Rupe looking up.

It sparks on [the projector] & shoots a beam of bright light into the clouds.

Rupe looks up at his hand-work, smiles

Figure 1: Morgan 2006, Hunt Angels, Storyboard

Figure 2: Morgan 2006, Hunt Angels, Digital Composite

Shooting Script: Rupe and Alma Street Sequence

This short sequence was one of the most complex sequences to design, film and composite. We wanted to create the illusion that the actors were walking past the lit windows of a large department store at night. In order for the illusion to work, the lighting of the moving actors in the studio had to perfectly match the lighting in the original photographs. This was skilfully and painstakingly achieved by the Director of Photography, Jackie Farkas.

STILLS - (Digital Insert) (B&W 1935) A moody photograph of a shadowy rain soaked lane in the city. RUPE, his film can under his arm, walks dejectedly under a street lamp. ALMA rounds the corner and hurries after him. She reaches him and begins to talk. We cannot hear what she is saying, but we can see it’s enthusiastic.

They talk in front of a shop front window displaying a new Hollywood movie. They fail to notice them. They are too engrossed in each other. |

Figure 3: Morgan 2006, Hunt Angels, Digital Composite

The above shot, the last in the sequence, was the most time-consuming to set-up and film inside the studio. The ‘live action’ reflection of Rupe and Alma in the window of the archival still background was achieved by the use of two 16mm cameras that recorded each take simultaneously. One camera was placed in front of the actors standing before the Green Screen. The other camera was positioned behind the Green Screen where a small hole had been cut out, large enough to film through. The take from this camera was later digitised and composited in the still photograph as the ‘live action’ reflections of the two characters in the window.

Shooting Script: Rooftop Escape

This is one of my favourite effects shots from the finished film. It was not originally scripted as a digital composite. We initially intended to use a rooftop location that we would film the actors on. However, this proved to be too expensive for our budget. It turned out to be cheaper to use green screen and desktop compositing techniques. The result, I believe, was far more aesthetically pleasing.

STILLS - (Digital Insert) (B&W 1935) The torch beam runs up the side of the studio building. Above, silhouettes of the film crew and actors scramble across the roof. |

Figure 4: Morgan 2006, Hunt Angels, Digital Composite

The rooftop shot was filmed entirely inside the studio against green screen. We used one single section of low roofing constructed by the props department. This section was filmed three separate times with different actors. These sections were later composited together to produce the three-pointed rooftop. The moon, stars and telephone poles were later added in by the digital designers.

Conclusion

The rapid development of digital technologies opens up exciting possibilities for low-budget cinematic story-telling. Through the use of non-proprietary computer based digital imagining products and the skills of a growing fraternity of digital designers, we were able to deploy contemporary electronic means to fuse together the story of two filmmakers ‘lost’ from our written history with ‘lost’ images of Sydney of the era in which they lived.

Other digital medias, such as the Internet, are providing researchers and writers with an access to a visual past which may have once been denied them. These technologies hold the potential to deliver up un-tapped source materials for the re-telling of history in a multi-media age and, thereby, evoke the historical imagination and stimulate an interest in that past.

References

Adobe, Hollywood Effects on the Desktop: the Use of Abode, After Effects and Photoshop in the Making of The Aviator, www.adobe.com/products/aftereffects/pdfs/the_aviator_021405.pdf, accessed on October 2, 2006

Brinkmann, R. (1999) The Art and Science of Digital Compositing, San Fransisco: Morgan Kaufmann

Brown, B. (2002) Interviewed by Alec Morgan, Sydney

Gadd, N. (2006) “Documentary and the Discontents”, InsideFilm, no.84 (February) pp.44

Kathner, R. (1945) Let’s Make A Movie, Sydney: Currawong Press

Morgan, A. (2005) Hunt Angels: a feature-length documentary drama, Final draft

Picman, The On-line Pictures and Manuscripts Collection of the State Library of New South Wales, www.sl.nsw.gov.au/picman/about.cfm, accessed October 24, 2006

Richards, R. (2004) “An Aesthetic or Anaesthetic? Developing digital aesthetics of Production” in Journal of Media Practice 5:3 pp.145

Sias, R. (2006) Bowling for Columbine: I was Character Designer for the Animation, Bowling4Columbine on-line newsletter, www.ryansias.com/moore_mainpage.htm, accessed October 16, 2006

Ward, P. (2005) “Shape-shifting realism” in Sight & Sound vol. 16 no. 8 p.42

Filmography

Bowling for Columbine (2002), Michael Moore, Dog Eat Dog Films, USA

Hunt Angels (2006), Alec Morgan, Film Art Doco & BluSteal Films, Australia.

Falling for Fame (1934), Rupert Kathner, Australia

The Kid Stays In The Picture (2002), Nanette Burstein & Brett Morgen, Highway Films, USA

The Pyjama Girl Murder Case (1939), Rupert Kathner, Australia

Waking Life (2001), Richard Linklater, IFC Productions, USA

The surviving films of Rupert Kathner and Alma brooks are held at the National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Their synopsis and viewing copy references can be seen on-line at www.nfsa.afc.gov.au.